Anyone who is a member of a writing group is regularly beaten over the head with certain basically good, but occasionally clichéd, rules. Improperly applied, this mindless interpretation of proper grammatic style can inhibit an author’s growth.

Anyone who is a member of a writing group is regularly beaten over the head with certain basically good, but occasionally clichéd, rules. Improperly applied, this mindless interpretation of proper grammatic style can inhibit an author’s growth.

These rules are fundamentally sound, but cannot be rigidly applied across the board to every sentence, just “because it says so in Strunk and White.” I rely on the Chicago Manual of Style, but I also understand common sense.

English is a living language. As such it is in a continual state of evolution and phrasing that made sense one-hundred years ago may not work well in today’s English.

We may be writing a period piece, but we are writing it for modern readers.

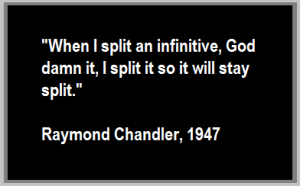

You can split an infinitive: it is acceptable to boldly go where you will.

You can begin a sentence with a conjunction if you so choose. And no one will die if you do.

Stephen Pinker discusses many rules in his controversial book, The Sense of Style, and finds that some of them no longer make sense.

For example, Pinker points out that “The prohibition against clause-final prepositions is considered a superstition even by the language mavens, and it persists only among know-it-alls who have never opened a dictionary or style manual to check.”

He notes that rigidly following “the rules” would have you doing silly things like turning “What are you looking at?” into “At what are you looking?” I don’t know about you, but for me the first example is preferable.

In the example, the word at is a preposition, and placing it after looking makes it a clause-final preposition. Such a construct is technically a no-no, but I suggest you break that rule.

We are constantly told that we need to make our verbs active, rather than relying on passive constructions, and for the most part, this is true. But Pinker reminds us that “The passive is a voice and not a tense.” There are times when the use of passive phrasing is appropriate.

We are constantly told that we need to make our verbs active, rather than relying on passive constructions, and for the most part, this is true. But Pinker reminds us that “The passive is a voice and not a tense.” There are times when the use of passive phrasing is appropriate.

Consider the difference between ‘the cat scratched the child’ and ‘the child was scratched by the cat.’ The second sentence is written in the passive voice, and in this context the active voice is the one I would choose because it is simpler and less fluffy.

Pinker agrees with me that there are contexts in which the passive is preferable. Quote from The Sense of Style: “Linguistic research has shown that the passive construction has a number of indispensable functions because of the way it engages a reader’s attention and memory.”

And in writing, context is everything.

For most genre work, editors push for active voice, but truthfully, mainstream fiction and literary fiction can use the passive voice and still sell boatloads of books. Some of the most beautiful prose out there in genre fantasy mixes passive voice in with the active, and when done right it is immersive.

Patrick Rothfuss’s Name of the Wind is one example, and Neil Gaiman’s Stardust is another.

Patrick Rothfuss’s Name of the Wind is one example, and Neil Gaiman’s Stardust is another.

These books are best sellers because both Rothfuss and Gaiman understand how to craft prose that mingles passive and active phrasings, drawing us into their work. They choose when to use passive phrasing, and apply it appropriately so the narrative is a seamless blend of properly constructed sentences chosen to reflect their distinct voices.

The modern prohibition against passive phrasing exists for a reason: improperly and excessively used, the passive voice can weaken your narrative.

Knowledge of grammar and sentence construction is critical if you are an author: Sloppy grammar habits show that your work is badly crafted.

Your voice is the way you habitually phrase things despite your vast knowledge of how grammar is correctly used. Take a look at the great authors: Raymond Chandler, Ernest Hemingway, F.Scott Fitzgerald, and James Joyce: these authors each had such a distinctive voice that when you read a passage of their work, you knew immediately who you were reading.

They ALL broke the rules in their work and were famous for doing so.

However, they understood the rules they were breaking and broke them deliberately and selectively in the crafting of their narrative.

However, they understood the rules they were breaking and broke them deliberately and selectively in the crafting of their narrative.

Imagine a story set in an expensive restaurant. This story revolves around a marriage that is disintegrating. The couple, Jack and Diane, dine in silence. The food is important, but only because of what it represents. How do you convey this?

The steak was well-prepared and melted in Jack’s mouth. Nevertheless, Diane wielded her knife like a surgeon, cutting her meat into tiny, uniform chunks, chewing each bite slowly before swallowing. Jack imagined her carving his heart similarly, chewing it carefully and then spitting it out.

“The steak was well-prepared and melted in Jack’s mouth” is written with a passive voice, and that is okay. The important thing is Jack’s observation of Diane and her mad knife skills. You don’t need to say “The chef had prepared the steak perfectly.” Unless he is having an affair with Jack or Diane, the chef who prepared the tender steak is not important and doesn’t need to be mentioned.

“The steak was well-prepared and melted in Jack’s mouth” is written with a passive voice, and that is okay. The important thing is Jack’s observation of Diane and her mad knife skills. You don’t need to say “The chef had prepared the steak perfectly.” Unless he is having an affair with Jack or Diane, the chef who prepared the tender steak is not important and doesn’t need to be mentioned.

Steven Pinker has some words of wisdom for would-be editors: “It’s very easy to overstate rules. And if you don’t explain what the basis is behind the rule, you’re going to botch the statement of the rule—and give bad advice.”

Knowing what the rule is and why it exists allows you to choose to break it if that is your desire.

Writing style is a combination of so many things. It is how you speak through your pen or keyboard. Craft your prose with an eye to what is important to your story, and say it with your voice. With that said, your voice should not be so distinct and loud that it makes your prose obnoxious. A good editor will understand the difference and guide you away from bad writing, helping you find your voice in such a way that your work will be a joy to read.

Every character, ever narrator, has his/her own true natural voice and if the writer wishes readers to accept that voice as authentic to the character or narrator, it must be present flaws and all (with some tweaking for readability). Do not worry so much about writing grammatically perfect language unless your protagonist is an English professor or other well-read, learned person.

You gots to talk like your friend talks or t’ain’t real nuf to be taken as real, y’hear?

LikeLike

@Professor–I completely agree. To break the rules most creatively, one must understand the rules one is breaking.

LikeLike

This is so true. Most of the authors I read regularly have a very distinct voice that does not follow ALL the rules!

LikeLike

@Dennis–this writing journey is not as simple as it seems on the surface!

LikeLike

That is for certain!

LikeLike

Hi Connie, great post!

One question for you though—I’m about 40 pages into the Name of the Wind and, while I am never bothered by writers using passive voice and in well-written prose often don’t even notice when they do, I’ve found Rothfuss’s incessant use of passive voice actively distracting. As this is the beginning of his first novel, I’m hoping this eases up and it becomes more the way you describe. Do you remember it being especially bad at the beginning before hopefully settling into a more balanced mixture?

LikeLike

It may be that you just don’t like his style. He’s a literary writer, and writes in the passive voice, which I like for the poetic cadence to his work when read aloud. It’s perfectly fine to dislike a famous author’s style! I’m not George R.R. Martin fan, although I adore him as a human being! It’s okay to not finish if you don’t enjoy it 😀

LikeLike

Very true, the beauty of books is how many choices you have! I’m sticking with it for now though as I quite like some elements of it and hope I’ll settle into the style.

And if not—onto the next!

P.S. I love your passive example about the steak

LikeLiked by 1 person