Much of my blog time revolves around grammar and the mechanics of writing. As authors, it’s important to understand the rules of how the language in which we write works, no matter what that language is. Yet powerful writing often breaks those rules, and we are better for having read it.

Much of my blog time revolves around grammar and the mechanics of writing. As authors, it’s important to understand the rules of how the language in which we write works, no matter what that language is. Yet powerful writing often breaks those rules, and we are better for having read it.

So why am I always pressing you to buy and use the Chicago Manual of Style?

Authors must know the rules to break them with style.

Readers expect words to flow in a certain way. If you break a grammatical rule, know what you are breaking and be consistent about it.

Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Alexander Chee, and George Saunders all have unique voices in their writing. Each of these writers has written highly acclaimed work. Their prose is magnificent. When you have fallen in love with one of these authors’ works, you will recognize their voice.

Ernest Hemingway used the word “and” in place of commas too freely.

Alexander Chee employs run-on sentences and dispenses with quotation marks.

James Joyce wrote hallucinogenic prose and at times dispensed with punctuation completely.

George Saunders writes as if he is speaking to you, and is, at times, choppy in his delivery.

But their voices work. They each break certain rules as set down by Strunk and White, but they produce brilliant prose that stands the test of time. Readers fall into the rhythm of their prose.

I will admit, I had to take a college class to be able to understand James Joyce’s work, and I did have to resort to the audio book for Alexander Chee’s work. It’s the hypercritical editor coming out in me, making it difficult for me to set that part of my awareness aside. It’s my job to notice those things.

I can hear you now: these are literary authors, and you are writing genre fantasy fiction or sci-fi. Shall I toss out a few more names?

Tad Williams mixes his styles. His Bobby Dollar series is Paranormal Film Noir: dark, choppy, and reminiscent of Chandler’s Philip Marlowe stories. In this series, he seems to be somewhat influenced by the style of crime authors, such as Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett. It is a quick read and is commercial in that it is for casual readers.

Raymond Chandler was the creator of Philip Marlowe, the original hard-boiled, disillusioned, copper-turned-private-eye. His people take center stage, rather than the violence that characterizes so many detective novels of his era.

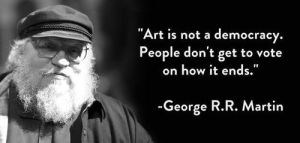

In his article, The Chandler Style, Martin Edwards writes: Devising puzzles was always less important to him than style. He said, ‘I don’t really seem to take the mystery element in the detective story as seriously should,’ and joked about solving plot problems by having a man come to the door with a gun Style mattered much more: ‘I had learn American just like a foreign language. To learn it I had to study and analyse it. As a result, when I use slang . . . I do it deliberately.’ And as he told one magazine editor whose proof-reader presumed to tidy up the Chandler grammar, ‘When I split an infinitive, God damn it, I split it so it will stay split.’

Chandler understood how grammar worked. He knew what he was doing and did it deliberately. He was able to convey (to those who didn’t appreciate his style) why he broke those rules and was secure enough in his choice to continue writing in his own voice.

But Chandler also had to deal with the sort of sniping we all must deal with in our writing groups. Wikipedia says: The high regard in which Chandler is generally held today is in contrast to the critical sniping that stung the author during his lifetime. In a March 1942 letter to Blanche Knopf, published in Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, he wrote, “The thing that rather gets me down is that when I write something that is tough and fast and full of mayhem and murder, I get panned for being tough and fast and full of mayhem and murder, and then when I try to tone down a bit and develop the mental and emotional side of a situation, I get panned for leaving out what I was panned for putting in the first time.”

Yet, although he writes Bobby Dollar in a Chandler-esque style, Tad Williams’s Memory Sorrow and Thorn Trilogy is true epic fantasy, with lush, poetic prose, multiple story-lines, and dark themes. It is written for serious fantasy readers who want nothing less than the big novel. The story starts slow, but the powerful writing has generated millions of fans who are thrilled to know he has set more work in that world.

Beginning slow, going off on side quests, writing poetic prose, and gradually working up to an epic ending is highly frowned upon in today’s writing groups, but Tad broke that rule and believe me, it works.

Roger Zelazny wrote one of the most famous fantasy series of all time, the Chronicles of Amber, and was famous for his crisp, minimalistic dialogue, and he was also heavily influenced by the style of wisecracking hard-boiled crime authors like Chandler.

Most readers are not editors. They will either love or hate your work based on your voice, but they won’t know why. Voice is how you break the rules, but you must understand what you are doing, and do it deliberately. Craft your work so it says what you want, in the way you want it said.

If your editor asks you to change something you did deliberately, you are the author. Explain why you want that particular grammatical no-no to stand, and your editor will most likely understand. If you know the rule you are breaking, you will be better able to explain why you are doing so.

If your editor asks you to change something you did deliberately, you are the author. Explain why you want that particular grammatical no-no to stand, and your editor will most likely understand. If you know the rule you are breaking, you will be better able to explain why you are doing so.

However, if I am your editor, you must be prepared to break that rule consistently. Readers do notice inconsistencies.

I can only dream of the day when people will find my writing worth criticizing!

Meanwhile, the style (I think) should match the nature of the story and especially the mindset and education level of the narrator. When we are told to make each character sound different, we further seek drive writers insane. And yet, such insanity (especially schizophrenia) assists in role playing various fictitious entities. I find myself going off from the writing desk still stuck in the mindset of this or that character, which makes for great conversations (i.e., bizarre) at the grocery.

The hardest task (I think) is to make each book’s protagonist sound different and act differently from the protagonist in another book by the same author, i.e., avoiding stock characters.

That having been said, I know for a fact I adopted two particular writing quirks of Mr. Zelazny simply from reading all of his oeuvre. One I shall admit to is the use of a comma separating two actions without using a conjunction. For example: He bedded down for the night, closed his eyes. The Z-man does this a lot and so I borrowed it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

@Professor: You raise several excellent points. We shall, no doubt, discuss methods of avoiding stock characters at length later 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on .

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love writers who break up style. After you’ve read so much it’s nice to be surprised by something different.

LikeLike

Hello! I agree. And that is where an author’s individual voice and style comes into play. Knowing the rules and why they exist allows you to break them with intention.

LikeLiked by 1 person