Last week, we discussed how the descriptive narrative of a story is comprised of three aspects:

Narrative point of view is the perspective, a personal or impersonal “lens” through which a story is communicated.

Narrative time is the grammatical placement of the story’s time frame in the past or the present, i.e., present tense (we go) or past tense (we went).

Narrative voice is how a story is communicated. It is the author’s fingerprint.

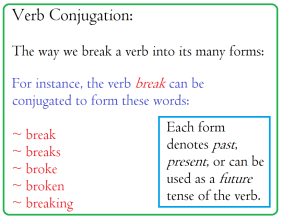

Today we’re discussing how narrative time, or what we call tense, affects a reader’s perception of character development. In grammar, tense is a category that expresses time reference. Tenses are usually shown by how we use the forms of verbs, particularly in their conjugation patterns. The main tenses found in most languages include the past, present, and future.

Today we’re discussing how narrative time, or what we call tense, affects a reader’s perception of character development. In grammar, tense is a category that expresses time reference. Tenses are usually shown by how we use the forms of verbs, particularly in their conjugation patterns. The main tenses found in most languages include the past, present, and future.

The way that narrative tense affects a reader’s perception of characters is subtle, an undercurrent that goes unnoticed after the first few paragraphs. It shapes the reader’s view of events, but on a subliminal level.

Every story is different and requires us to use a unique narrative time.

Tense conveys information about time. It relates the time of an event (when) to another time (now or then). The tense you choose indicates the event’s location in time.

Consider the following sentences: “I eat,” “I am eating,” “I have eaten,” and “I have been eating.”

All are in the present tense, indicated by the present-tense verb of each sentence (eat, am, and have).

Yet, they are different because each conveys unique information or points of view about how the action pertains to the present.

We often “think aloud” in writing the first draft. We insert many passive phrasings into the raw narrative, words that I think of as traffic signals. These words are a shorthand that helped us get the story down when we were writing the raw first draft, a guide that now shows us how we intend the narrative to go.

Subjunctives are insidious. The subjunctive (in the English language) is used to form sentences that do not describe known objective facts. In other words, subjunctives describe unknown intangible possibilities.

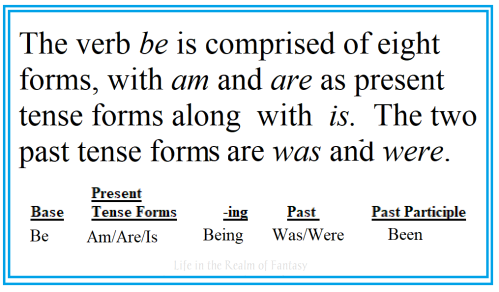

Maeve Maddox, in her article The Many Forms of the Verb To Be, says:

Of all Modern English verbs, to be has the most forms: am, are, is, was, were, be, being, been. In addition, the helping verb will is used to form a future tense with be (e.g. I will be with you in a minute.)

The forms are so different in appearance that they don’t seem to belong to the same verb. The fact is, they don’t. Oh, they do now, but they came from three different roots and merged in the Old English verbs beon and wesan.

William Shakespeare said it best in Hamlet: “To be or not to be… that is the question.”

Should he exist, or should he not exist—for the deeply depressed Dane, suicide or not suicide is the question. In his soliloquy, Hamlet contemplates death and suicide. He regrets the pain and unfairness of life but ultimately acknowledges that the alternative might be worse.

Subjunctives are small verbs of existence, but just like adverbs, they are telling words. These words fall into our narrative in the first draft because they are signals for the rewrite.

In the rewrite, we look for the code words that tell us the direction in which we want the narrative to go.

In the rewrite, we look for the code words that tell us the direction in which we want the narrative to go.

We look at each instance and rewrite the paragraph to show the event rather than tell about it.

If we write a sentence that says a character was hot and thirsty, we leave nothing to the reader’s imagination. The reader is on the outside, looking in.

When we take that experience of thirst and make it immediate, no matter what narrative tense we are writing in, it changes everything.

Which sentence feels stronger, more pressing?

- They were hot and thirsty.

- They trudged on with dry, cracked lips, yearning for a drop of water.

- I walk toward the oasis with dry, cracked lips and parched tongue.

The way we show the perception of time for these thirsty characters is the same – the narrative is in the past tense in the first two cases and the present in the third.

Each sentence says the same thing, but we get a different story when we change the narrative tense, point of view, and verb choice.

“Were” is a verb, but it is subjunctive and is perceived as a weak word, where “trudged” conveys power. The narrative time in which the story is set (past or present tense), verb choice, and expansion of the imagery – these combine to change how we see the characters at that moment.

No matter what narrative tense you choose for your story, using strong verbs to describe their actions and emotions will reinforce the reader’s connection to the characters.

For my short story, View from the Bottom of a Lake, the narrative tense that worked best was a past tense, close third person.

Peggy Jayne smiled. Beneath the green-glittering gaze, her toothsome smile flayed her daughter, leaving Sarah breathless, panicking and longing for her lake.

Sometimes the only way you can get into a character’s head is to write them in the first-person present tense, which happened to me with Thorn Girl. I struggled with her story for nearly six months until a member of my writing group suggested changing the narrative tense and point of view.

Sometimes the only way you can get into a character’s head is to write them in the first-person present tense, which happened to me with Thorn Girl. I struggled with her story for nearly six months until a member of my writing group suggested changing the narrative tense and point of view.

Once I did that, the story fell out of my head the way I had envisioned but couldn’t articulate, and I wrote it in one evening.

My first instinct is to shake my head and back away.

But I don’t. Long ago, my Lady told me that in every life, a time will come when you arrive at a precipice. You must either leap the chasm or fall to your death.

I stand at that place now.

In traditional first-person POV, the protagonist is the narrator. We must keep in mind that no one ever has complete knowledge of anything, so the first-person narrator cannot be omnipotent.

Every story is unique, and some work best in the past tense, while others need to be in the present. When we begin writing a story using a narrative time that is unfamiliar to us, we may have trouble with drifting tense and wandering narrative points of view.

Every story is unique, and some work best in the past tense, while others need to be in the present. When we begin writing a story using a narrative time that is unfamiliar to us, we may have trouble with drifting tense and wandering narrative points of view.

This happens most frequently if you habitually write using one mode, say the third-person past tense, but switch to the first-person present tense.

For this reason, when you begin revisions, it’s crucial to look for your verb forms to make sure your narrative time doesn’t inadvertently drift.

PREVIOUS POSTS IN THIS SERIES:

Storyboarding character development

Character Development: Motivation drives the story

Character Development: Emotions

Character Development: Showing Emotions

Character Development: Managing the Large Cast of Characters

Character Development: Point of View

This post: Character Development: Narrative Time

Credits and Attributions:

Maeve Maddox, The Many Forms of the Verb To Be, Copyright © 2007 – 2021 Daily Writing Tips. All Right Reserved

Quote from View from the Bottom of a Lake, © 2020 Connie J. Jasperson. Story first appeared in the anthology Escape, published by the Northwest Independent Writers Association and edited by Lee French.

Quote from Thorn Girl, © 2019 Connie J. Jasperson. Story first appeared in the anthology Swords, Sorcery, and Self-rescuing Damsels, edited by Lee French and Sara Craft.

This is very helpful. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Ellen.

LikeLike

“… we may have trouble with drifting tense and wandering narrative points of view.”

Guilty as charged! LOL!

These…

“We look at each instance and rewrite the paragraph to show the event rather than tell about it.”

… are golden words! So simple and practical, yet I’ve never looked at a first draft, or any part of a manuscript this way. Too busy overthinking and over-complicating things. 😀

Thanks, Connie!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Felicia. I have an amazing writers’ group, so I learn as I go!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog.

LikeLike

Thank you, Chris ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Connie 🤗❤️🤗

LikeLike

I confess to being guilty, at least in the past. I remember reading Paul Hoffman’s (sometimes wonderful, often seriously flawed) fantasy series “the left hand of god” where rather than adjusting tenses he simply makes pronouncements such as “Listen”, “Attend”, “Imagine” the following piece can then be written in present tense as you are already aware that he talks of the past. In essence a cheat but it works and gives you free reign.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wrote the first draft of one of my early novels in third-person present tense. That didn’t work well, so I changed it. What an utter nightmare that was, but boy did I learn a lot through the experience.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on OPENED HERE >> https:/BOOKS.ESLARN-NET.DE.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the reblog, Michael!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you too, Connie, for sharing another important piece of grammar, i sometimes have to know. I always had thought German grammar would be worst. 😉 xx Michael

LikeLike

Personally I can’t get into a book written in present tense, whether it’s first person or third. I feel like I’m reading a movie script.

Short passages that require immediacy are different, Dickens was known for those. But not whole books. I’ve seen very few that didn’t slip into past tense periodically and confuse the whole matter as well.

Perhaps growing up with the Classics has made me a dinosaur.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Welcome the the Dinosaur Club! High five!

That feeling of reading a movie script may be what appeals to many readers. I do prefer a close third person past tense POV, but am glad when a narrative in the first person present tense hooks me.

Reading the classics influenced my writing life too, along with parents who loved words the way James Joyce did, using and abusing them with abandon.

LikeLike