Whether we show it in the prologue or the opening chapter, the first event, the inciting incident, is the one that changes everything and launches the story. The universe that is our story begins expanding at that moment.

The first incident has a domino effect. More events occur, pushing the protagonist out of his comfortable life and into danger. Fear of death, fear of loss, fear of financial disaster, fear of losing a loved one—terror is subjective and deeply personal.

The first incident has a domino effect. More events occur, pushing the protagonist out of his comfortable life and into danger. Fear of death, fear of loss, fear of financial disaster, fear of losing a loved one—terror is subjective and deeply personal.

I love stories about good people solving terrible problems, but I want them to mean something.

While I have experienced violent situations, I’ve also faced many things that shook my world but didn’t threaten my physical safety.

Arguments and confrontations are chaotic, leaving us wondering what just happened. We want to convey that sense of chaos in writing, but we must consider the reader. Readers want to see the scene and understand what they just read. We must design every action scene to ensure they fit naturally into a narrative from the first incident onwards.

The threat and looming disaster must be made clear to the reader at the outset. Nebulous threats mean nothing in real life, although they cause a lot of stress in our daily lives.

Those vague threats might be the harbinger of what is to come in a book, but they only work if the danger materializes quickly and the roadblocks to happiness soon become apparent.

Resolving disaster is the story. Hold the solution just out of reach for the following ¾ of the narrative. Every time we nearly have it fixed, we don’t, and things get worse.

The arc of the story begins with the first event, the inciting incident. The story’s arc occurs because the characters keep reaching for a resolution but can’t quite grasp it. Every attempt is blocked somehow.

The One Ring, Peter J. Yost, CC BY-SA 4.0

The characters reap the rewards of minor successes but not the golden ring. Those small rewards keep hope alive and keep the reader involved.

If the first problem was taken care of too quickly, why? What sort of trap was laid, and why did the characters take the bait?

If we do this right, we will move our readers emotionally and they will remain invested in our book.

I mentioned that confrontations are chaotic. It’s our job to control that chaos and make a narrative out of it. Nothing upsets a reader more than a book where the author contradicts something that was said or that happened before.

I choreograph action sequences, which can take a little time. Each character’s reactions must be portrayed in such a way the reader doesn’t say, “He wouldn’t do that.”

In real life, people don’t all react the same way. So, our characters can’t all be superheroes in a fight scene. It’s easy to lose the characters’ individuality in the jumble of actions that a confrontation is.

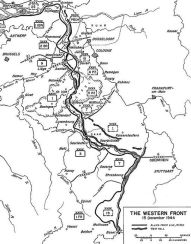

If your violence is war, go to history and see how battles were waged historically. Any war will do, but let’s say you are writing an account of a soldier’s experiences in modern warfare. Go to the Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Counteroffensive.

US Army Center for Military History, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

I’ve used this battle as an example before because it was a pivotal point in World War II, and the placement of all the forces on both sides is well documented.

Also, one of my uncles fought and was wounded in that battle. Uncle Don came home with a metal plate in his head. American forces endured most of the attack, suffering their highest casualties of any operation during the war.

But you can look at any historical battle. Just remember that even though your book may explore a real soldier’s experiences, you are still writing a fantasy. The past is just hearsay, stories written by the victors. The future is a rumor that may not happen. The only moment that happens for sure is this moment, that moment you experience now.

Our characters exist in their own now, and the inciting incident kicks off their story. Perhaps the soldier’s inciting incident occurs when they join the army. From that point on, the actions and reactions of our soldiers must be logical even amidst the chaos of battle, or the reader will skip over that scene and possibly put the book down.

We make our characters knowable and likable (or not, as the case may be) through physical actions and conversational interactions. In the early part of the story, each scene should illuminate the characters’ motives. The reader must gain information at the same time as the protagonist does.

However, the reader has an edge—they will be offered clues from the antagonists’ side, which the characters don’t know. The antagonist’s actions will affect the plot in the future. Even if the antagonist isn’t an overt enemy at the outset, the readers’ knowledge creates a sense of unease, a subliminal worry that things will go wrong.

However, the reader has an edge—they will be offered clues from the antagonists’ side, which the characters don’t know. The antagonist’s actions will affect the plot in the future. Even if the antagonist isn’t an overt enemy at the outset, the readers’ knowledge creates a sense of unease, a subliminal worry that things will go wrong.

Through the first half of the book, subtle foreshadowing is essential. This knowledge raises the stakes, increasing the tension.

Next week, we will look at ways to choreograph confrontations and violent encounters.

Reblogged this on Kim's Musings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤ Thank you for the reblog!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤ Thank you, Chris ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Welcome, Connie 🤗❤️🤗

LikeLike

The story of my life . . . LOL —

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hah! You aren’t alone in this, my dear friend!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on NEW BLOG HERE >> https:/BOOKS.ESLARN-NET.DE.

LikeLike

Thanks for another very interesting overview, Connie! I love the examples, and now i am seeking for my own inciting incident, and hope also to find solutions for my disaster. 😉 Best wishes, Michael

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤ Michael, you are always so kind. I thank you for the reblog, and know you will do well in your writing.

LikeLike