A few years ago, about ten minutes into a NaNoWriMo write-in, I accepted a dare to write an Arthurian tale with a steampunk twist.

I quickly regretted that decision.

I quickly regretted that decision.

Everyone was quietly typing away in that coffee shop, getting impressive word counts.

But not me.

I sat there asking myself where Arthurian and steampunk connect well enough to make a story. On the surface, they don’t. I experienced the mental blankness we all feel when a story refuses to reveal itself.

Arthur and his court originated as ordinary 5th or 6th-century warlords. But the tales featuring them were written centuries later. Their 11th-century chroniclers presented them in contemporary armor as worn by Crusaders and with medieval customs and moral values.

Arthur and his court originated as ordinary 5th or 6th-century warlords. But the tales featuring them were written centuries later. Their 11th-century chroniclers presented them in contemporary armor as worn by Crusaders and with medieval customs and moral values.

Over the centuries, subsequent authors continued to romanticize the story but with their own twist. Alfred Tennyson’s Idylls of the King reworked the entire narrative of Arthur’s life to fit the romantic ideals of the Victorian era.

When I agreed to the challenge, I decided my protagonists must be real people, flesh and blood. They would be subject to the same emotions and physical needs as any other person.

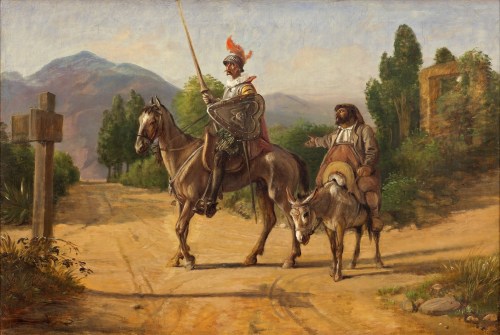

Galahad is traditionally portrayed as a knight errant, which means wandering. The knight-errant was a popular character in medieval romance literature. Miguel de Cervantes‘ mad knight, Don Quixote, believed he was a knight errant and lived his fantasy with hilarious abandon.

Wilhelm Marstrand, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (after 1847) via Wikimedia Commons

The Chivalric Code was a system of values combining a warrior culture, devotion to the Christian faith, and courtly manners. Adherence to the code of chivalry ensured a knight epitomized bravery, honor, and nobility.

They roamed the land looking for heroic tasks, engaged in knightly duels, or went in pursuit of courtly love. The medieval romance of highly ritualized courtly love was a rigid literary structure. It defined the written behaviors of noble ladies and their lovers and was woven with the principles of chivalry.

Medieval and Victorian authors loved superheroes. To them, nothing was more impossible or super-heroic than a man who lived a virtuous and self-sacrificing life.

I randomly picked an Arthurian knight, Galahad, and began making notes as I pondered the problem. What kind of a person might Galahad have been had he truly existed?

The established canon dictates that Galahad isn’t attracted to women. He goes on quests to find strange and magical objects, such as the Holy Grail. Since he’s not attracted to women, how about men? I asked myself, what if Galahad and Gawain were lovers?

And what really happened after the Grail was found? With no answer to that, I moved on to the next question. Where does steampunk come into the story? Steampunk is science fiction set in Edwardian times using only technology available during the reign of King Edward VII, who reigned from 1901 to 1910.

Thinking about what steampunk really is triggered the cascade of plot points:

What if finding the Grail somehow opened a door in time?

What if all the magic in the world vanished with the Grail?

What if Galahad was marooned in Edwardian England with Merlin?

How would Galahad get back to Gawain?

I sat in the coffee shop with my friends, all of them writing their novels. The November rains pounded on the windows and drowned passers-by, but I didn’t care—I had the plot I needed.

I am an abject fangirl for Don Quixote, so different versions of both Galahad and Quixote appear regularly in my work. Julian Lackland was inspired by my love of Don Quixote. they’re both insane, both deeply committed to doing good, and both have moments of hilarity mixed with the tragedy.

I am an abject fangirl for Don Quixote, so different versions of both Galahad and Quixote appear regularly in my work. Julian Lackland was inspired by my love of Don Quixote. they’re both insane, both deeply committed to doing good, and both have moments of hilarity mixed with the tragedy.

And Galahad–nowadays he’s considered a minor knight. However, what we regard as canon about him is taken from Sir Thomas Malory’s 1485 work, Le Morte d’Arthur, in which he and his quest have a prominent role.

Malory’s collection was a reworking of traditional tales that were hundreds of years old, even in his day. Also, he wrote it while in prison for a multitude of crimes, so we can be sure it’s not historically accurate.

Traditionally, Galahad is an illegitimate son of Lancelot du Lac. He goes on the quest to find the Holy Grail and immediately goes to heaven, raptured as a virgin.

When I began plotting the tale my friend had challenged me to write, I wondered why Malory said Galahad was raptured. Why was the notion of a virgin knight and being taken to heaven before death so important to medieval chroniclers? Why would they write a saint’s virginity and rapture as though it were factual recorded history?

People always rewrite history to suit the times in which they live.

Religion and belief in the Christian truths espoused by the Church were in the very air the people of the time breathed. All the physical and material things of this world were entwined and explained by the religious beliefs of the day.

Excalibur London_Film_Museum_ via Wikipedia

Literature in those days was filled with religious allegories, the most popular of which were the virginity and holiness of the Saints, especially those deemed holy enough to be raptured.

Death was the common enemy, an inescapable event kings feared as much as beggars did. Those saints who were raptured did not experience death. Instead, they were raised to heaven, living in God’s presence for all eternity.

Galahad as written by Malory and later authors never married. But humans tend to be human, so why assume he was a virgin? Galahad’s state of virginity and grace was written to exemplify what all good noblemen should aspire to.

The High Middle Ages was the period of European history that commenced around the 10th century and lasted until the 14th century (or so). That era saw a flowering of historical-fantasy writing among the clergy and educated nobility. Medieval chroniclers detailed the people and events of 300 to 400 years prior. Their sources were the oral histories as told in well-known bardic tales and local legends.

Malory was writing during the final decades of the Crusades and trying to fit the old stories into his modern time. Rumors and stories passed down became historical truths, reshaped to justify the desire for conquest. After all, the New World was just over the horizon, vast cities of Inca gold ripe for the taking.

We 21st-century authors have excellent records of 15th and 16th-century political struggles. Yet, we make things up about the Tudors and Elizabethans, because they were interesting people. We love to imagine what they must have been like.

We all know the written records from before the time of Elizabeth I are highly questionable. Sifting medieval fact from fiction is the life’s work of many historical scholars. However, they’re entertaining fantasy reads, leaving fangirls like me free to riff on them and create our own mythologies.

So, that is how my creative process works. Someone gives me an impossible idea, and I fight with it until it beats me. Once that idea has me by the throat, I know what has to be written. That tale became a short story, Galahad Hawke.

And sometimes a theme refuses to let go of me. I took Arthurian myth and the chivalric code and turned them inside out with the characters of Lancelyn and Galahad in Bleakbourne on Heath.

And sometimes a theme refuses to let go of me. I took Arthurian myth and the chivalric code and turned them inside out with the characters of Lancelyn and Galahad in Bleakbourne on Heath.

I feel quite sure I haven’t written my last Alternate Arthurian tale. Galahad Hawke may get an expansion into a novel–after all, he didn’t get the traditional happy ending.

Or maybe not. I do have an epic fantasy on deck so … maybe next year.