My weekend got derailed due to life cluttering it up with huge chunks of reality. I hate it when reality ruins my carefully plotted existence. So, instead of a new post, I am revisiting a post from 2023, a short story about a writer wrestling with her characters, objectives, and inventing risks with a dash of plot armor thrown in. I hope you enjoy it!

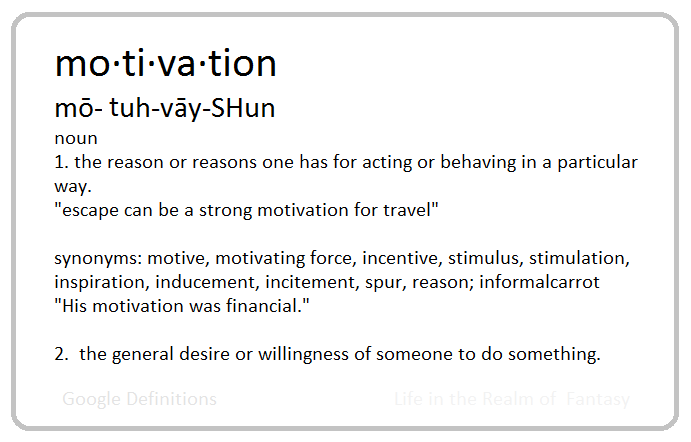

Sometimes I lose the plot. I know that character plus objective plus risk equals a story, but sometimes I can’t figure out the risk part.

Or the objective.

Characters can be tricky too. I have the plot armor part down well, but that’s just for the protagonist. Everyone else’s safety is fair game.

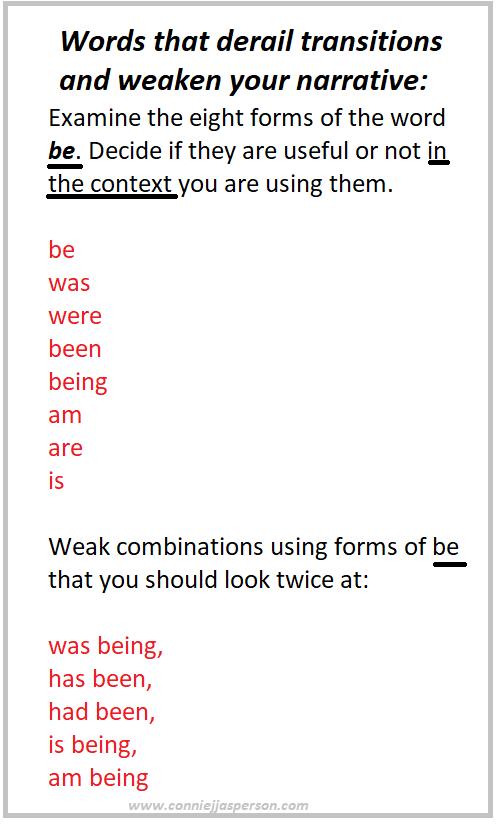

Sometimes I can’t find the plot even when I have an outline. I get to a place where I don’t know what to write, and the characters stand around doing nothing. I repeat the same old crisis with slight variations, which is tedious.

Sometimes I can’t find the plot even when I have an outline. I get to a place where I don’t know what to write, and the characters stand around doing nothing. I repeat the same old crisis with slight variations, which is tedious.

I thought I was writing a medieval fantasy, but according to a reddit thread I saw last week, dragons are overdone. Apparently, every fantasy features dragons.

Version 1.0.0

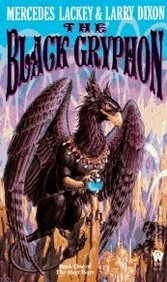

So now what? Griffons and manticores are prominent in medieval heraldry. There must be a reason for that. Mecedes Lackey did griffons, and I don’t want to copy her, so what is left? Unicorns?

My imagination is stuck on manticores, but even in fantasy they’re a rare beast. My hero just killed the last one so I’m unsure what to do now. Readers don’t like it when you milk a plot twist over and over, no matter how you change the scenery around it.

Sometimes I hate this job.

So, let’s look at the plot outline again. I’m all about giving my characters agency, but they have to work with me, give me a bit of help. Sometimes it takes divine intervention to get the plot moving again.

Today I have barely gotten started when I feel someone staring at me. Of course, it’s Sir Percival, looking over my shoulder. “Ahem.” He glares at me.

My characters no longer surprise me when they intrude, but being polite when I am disturbed is impossible. “What do you want? I’m a little busy.”

Sir Percival the Pointless says, “I rescued Lady Adeline, and the manticore is dead. Did you notice?”

Sir Percival the Pointless says, “I rescued Lady Adeline, and the manticore is dead. Did you notice?”

“Yes. I wrote that scene, and if I do say so myself, you were magnificent.” One problem with heroes is their desire for obscene amounts of praise.

“Thank you,” he replies, attempting to appear modest and failing. “Well, the thing is, Lady Adeline has thrown herself into wedding preparations.”

“I know.” I force myself to reply politely. “I’m designing the dress.”

“Well, you’ve been doing that for the last twenty pages, but who’s counting. Anyway, I’ve been booted outside because no one needs the groom until the big day. I need something to do.”

I never noticed it before, but Percy isn’t handsome when he scowls. Is there some way I can make him look like an adult? I don’t like beards, but he needs something to disguise his serious lack of a chin.

Percy the Pointless presses his attack. “You know, you’re really good at telling folks how to plot a book, but you suck at it yourself. We’re 25,000 words into your novel, and you’ve already wasted the big scene.”

What? He’s cruisin’ fer a bruisin’, as they say in my part of the world. “Watch it buddy. I wrote you, and I can easily delete you.” See? I can give a dirty look too.

He just shrugs. “I doubt you’re going to do that. You’ve spent two months on this epic. However, if you intend this to be a novel, you have at least 50,000 or so more words to write. I have nothing to do.”

I just realized that he has a slightly nasal whine. Oh, lord. I’ve written a whiney hero. However, the idiot has a point. I mistimed the big finale, so now I need a new objective for him, something entailing risk.

This could take a while. I gaze at Sir Percival the Prim, wondering what I was thinking when I made an idiot nobleman like him the star of this charade. “I can’t work with you staring over my shoulder. Look, why don’t you watch TV for a while?” I park him in front of the TV and give him the clicker.

This could take a while. I gaze at Sir Percival the Prim, wondering what I was thinking when I made an idiot nobleman like him the star of this charade. “I can’t work with you staring over my shoulder. Look, why don’t you watch TV for a while?” I park him in front of the TV and give him the clicker.

He looks first at me and then at the clicker. “What is this?”

Sighing, I show him how to turn the TV on and help him find something he’ll enjoy.

That takes an hour. Nine hundred channels and nothing interests him. Eventually we settle on old Star Trek reruns.

Finally, I am back at the keyboard and scraping the bottom of the barrel for a few more terrifying plot twists, hoping to keep this bad boy busy. All I can think of is manticores, but he’s already killed the only one that was left in the world.

Readers hate it when authors milk the same old plot twists.

“Ahem.”

I look up, only to see Duchess Letitia, Percy’s future stepmother-in-law standing at my elbow. “Yes?”

“I’m sorry to bother you, but we desperately need a certain magical ingredient for my special anti-aging cream.” She looks at me expectantly. “My stepdaughter’s wedding is a big deal. But the outline says Percival and Adeline will assume the throne upon their marriage. It’s canon now, so I’m done, kicked to the curb in the prime of my life.” She dabs the corner of her squinty eyes with a silken handkerchief. “You set this story in an era where women have few career options. I simply must have my beauty cream, or I won’t be able to snare a new hubby.”

“I’m sorry to bother you, but we desperately need a certain magical ingredient for my special anti-aging cream.” She looks at me expectantly. “My stepdaughter’s wedding is a big deal. But the outline says Percival and Adeline will assume the throne upon their marriage. It’s canon now, so I’m done, kicked to the curb in the prime of my life.” She dabs the corner of her squinty eyes with a silken handkerchief. “You set this story in an era where women have few career options. I simply must have my beauty cream, or I won’t be able to snare a new hubby.”

She has a point. “And that ingredient is…?” I hope it’s not a complicated thing because now I have two bored characters nagging the hell out of me.

A sharklike smile crosses her features. “Manticore’s milk.”

How odd. I never realized until this moment is how evil Adeline’s stepmother looks when she smiles like that. I love this woman.

She says, “I’m sure Sir Percival can get some since he’s just sitting around watching a magic box filled with other people having adventures.”

Duchess Letitia’s malicious smirk offers me no end of possibilities. I consider this for a moment. I could rewrite the original battle scene and subtract the dead manticore part.

He could get killed milking the manticore.

Or perhaps only maimed. After all, he does wear highly polished (but heavy-duty) plot armor.

Lady Adeline would have to rescue herself and then him. But what the hell?

He’s a hero, right? Bad days at the office come with the territory. A few dents in his plot armor should deflate his ego a bit.

I hoist myself out of my chair and walk to the living room.

There he is, sitting with his dirty boots propped on my coffee table.

Oh, yes. there will be mutilation in his future. I am going to stretch his plot armor to the limit. Rather than deleting his character from the story and starting anew, this jackass will live.

Percy the Prim and Proper will beg me to kill him off.

I can still change things up. The manticore that the idiot fought in chapter ten was only feigning death. Yes …. the nice, persecuted manticore lives, and now manticores are an endangered species.

Lady Adeline won’t approve of Percy attempting to murder the last one so there will be trouble in paradise. The noble idiot will have misadventure after misadventure until my new coffee table is paid for.

I feel invigorated. My plot is back on track, and I am inspired to write like the wind! “Percy, I have a task for you. Take this bucket and get some manticore’s milk. It’s a matter of life and death.”

He looks up. “I will in a minute, but I must see how this story ends. Captain Kirk might die if Spock can’t get the medicine!”

That’s another good plot twist. Note to self: have Duchess Letitia supervise stocking the medical supplies in Percy’s kit.

You know, now that I think about it, the duchess was wrong about one crucial thing. Nothing is canon until the book is published. I think the duchess deserves a much larger role in this story.

Excalibur London Film Museum via Wikipedia

So does my new protagonist, Lady Adeline.

A lady hero who needs armor and a sword.

And a horse.

A horse that’s a unicorn.

I love this job.

And the reddit trolls are wrong. Dragons are NOT overdone. In fact, I need a big, angry one now.

Artist: Adolf Kaufmann (1848–1916)

Artist: Adolf Kaufmann (1848–1916)

Sometimes I can’t find the plot even when I have an outline. I get to a place where I don’t know what to write, and the characters stand around doing nothing. I repeat the same old crisis with slight variations, which is tedious.

Sometimes I can’t find the plot even when I have an outline. I get to a place where I don’t know what to write, and the characters stand around doing nothing. I repeat the same old crisis with slight variations, which is tedious.

Sir Percival the Pointless says, “I rescued Lady Adeline, and the manticore is dead. Did you notice?”

Sir Percival the Pointless says, “I rescued Lady Adeline, and the manticore is dead. Did you notice?”

“I’m sorry to bother you, but we desperately need a certain magical ingredient for my special anti-aging cream.” She looks at me expectantly. “My stepdaughter’s wedding is a big deal. But the outline says Percival and Adeline will assume the throne upon their marriage. It’s canon now, so I’m done, kicked to the curb in the prime of my life.” She dabs the corner of her squinty eyes with a silken handkerchief. “You set this story in an era where women have few career options. I simply must have my beauty cream, or I won’t be able to snare a new hubby.”

“I’m sorry to bother you, but we desperately need a certain magical ingredient for my special anti-aging cream.” She looks at me expectantly. “My stepdaughter’s wedding is a big deal. But the outline says Percival and Adeline will assume the throne upon their marriage. It’s canon now, so I’m done, kicked to the curb in the prime of my life.” She dabs the corner of her squinty eyes with a silken handkerchief. “You set this story in an era where women have few career options. I simply must have my beauty cream, or I won’t be able to snare a new hubby.”