Words are the paints that we who write use to convey our ideas to the world. In English, which is a mash-up of several other languages, we have so many wonderful, wild words it is impossible to use them all in one book. Even the most comprehensive dictionaries can’t contain them all.

Commonly used words often fall out of fashion, while new words are being invented and dropping into use every day. I talked about this in my post, English – a Language Full of Bothersome Words #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy.

Commonly used words often fall out of fashion, while new words are being invented and dropping into use every day. I talked about this in my post, English – a Language Full of Bothersome Words #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy.

Let’s have a look at homophones – sound-alike and near-sound-alike words. Even experienced authors sometimes use the wrong word. As a reader, I notice the improper use of near homophones (words that sound closely alike). They stand out even when they’re spelled differently, BECAUSE they have different meanings.

We all know people who mispronounce words. I am certainly guilty of incorrect pronunciation whether conversing or reading aloud! The different meanings and proper enunciation of seldom-used words become blurred, and wrong usage becomes part of a writer’s everyday speech. We assume we know what that rarely used word means, and so we put it in the sentence.

And we do this more than once.

And unknowingly, we have created an embarrassing mistake. Fortunately, a good editor can easily guide us in the right direction.

New and beginning writers are often unaware that they habitually misuse common words until they begin to see the differences in how they are written.

New and beginning writers are often unaware that they habitually misuse common words until they begin to see the differences in how they are written.

A good example details the difference between two of the most commonly confused words: accept and except. Many people, even those blessed with a higher education, frequently mix these two words up in their casual conversation.

Accept (definition): to take or receive something; to receive with approval or favor.

- I accept this present.

- I accept your proposal.

Except (definition): not including, other than, leave out, exclude.

- Present company excepted.

- With the exclusion of ….

We accept that our employees work every day except Sunday.

English, being a mash-up language, has a long list of what I think of as cursed words to watch for in our writing.

Farther vs. Further: (Grammar Tips from a Thirty-Eight-Year-Old with an English Degree | The New Yorker by Reuven Perlman, posted February 25, 2021:

Farther describes literal distance; further describes abstract distance. Let’s look at some examples:

- I’ve tried the whole “new city” thing, each time moving farther away from my hometown, but I can’t move away from . . . myself (if that makes sense?).

- How is it possible that I’m further from accomplishing my goals now than I was five years ago? Maybe it’s time to change goals? [1]

When we use these words, we want to ensure we are using them correctly.

- Ensure: make certain something happens.

- Insure: arrange for compensation in the event of damage to (or loss of) property, or injury to (or the death of) someone, in exchange for regular advance payments to a company or government agency.

- Assure: tell someone something positively or confidently to dispel any doubts they may have.

When I need to use unfamiliar words in my work, I look them up. I want to be sure that what I write means what I intend it to.

I was raised by parents who never stopped educating themselves and who loved words. They wanted us to be as well educated as possible, and reading was not only encouraged, it was required. However, Dad Loved Words. Big words, small words, short words, long words. My Dad loved them all.

He spun hilarious yarns about the ‘Kamaloozi Indians’, a non-existent tribe whose beloved Chief, Rolling Rock, had gone missing. The tribe was so distraught that they posted signs at every mountain pass reading “Watch for Rolling Rock.”

Everything in his toolbox had a name that was his own invention: Screwdrivers were ‘Skeejabbers.‘

Everything in his toolbox had a name that was his own invention: Screwdrivers were ‘Skeejabbers.‘

Dad mangled words just because he loved the way they sounded. Sometimes he became so frustrated that he lost his words and resorted to creative cursing.

I confess, I’m just a product of my upbringing. I love obscure, weird words and regularly torment my adult children by using them in text messages.

But for the moment, let’s ignore the grandiose words and learn how to know when a word conveys the meaning you think it does, and when it does not. Using rare words correctly when they’re the only word that works is not pretentious.

However, ten-dollar words are to be avoided. If you pepper your narrative with highfalutin words, your readers might put the book down out of frustration, so go lightly.

Still, it never hurts to know the meaning and uses of words, even pretentious ones. Ten-dollar words #amwriting | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

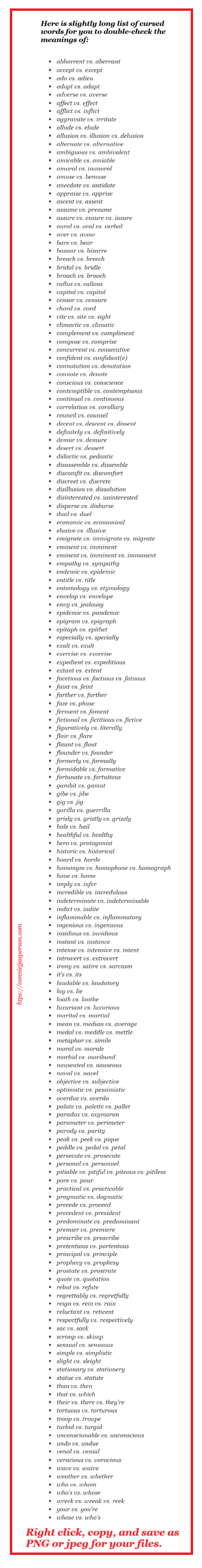

Below is an image containing a long list of words that are easily confused with sound-alike words. Feel free to right-click, copy, and save it as a reference. Using the wrong word completely changes the meaning of a sentence, so if you have doubts or if the word is unfamiliar, look it up. The internet is your friend!

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Farther vs. Further: (Grammar Tips from a Thirty-Eight-Year-Old with an English Degree | The New Yorker by Reuven Perlman, posted February 25, 2021 (accessed 25 Oct 2025).

Pingback: Reblog: Homophones: Wrangling Willful Words #writing | Jeanne Owens, author

Great information and well-needed revision for a European who writes in English. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yvonne, you are amazing. I only know one language, although I have a smattering of Deutsch. It is the residual of my junior year in high school, the class taught by Herr Meyer. All that I have retained these 55 years later consists mainly of drinking songs, lol!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The songs are fun, but be aware of the beer. Thanks for the lovely words.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here are a few more: bought/brought, birth/berth, metal/ mettle, practise/practice, and ine I actually saw in a traditionally published book: etched instead of inched.

peek, peak and pique are extremely common, and I could scream everything I see or hear ‘lay’ used instead of ‘lie’. To me it just sounds wrong, and I really can’t understand why it doesn’t to other people.

Thanks for the list, though. It’ll be very useful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Vivienne! I think “lay/laid and lie” cause the same uncertainty in a writer as “Who, Who’s, Whose, and Whom.” Sadly, many of us are not educated as children to understand their use. I was fortunate to have an editor who helped me understand, and still, despite knowing the different usages, I have to keep reminding myself of the mechanics. This is because I don’t use them that often in conversation and my lack of confidence shows!

LikeLike