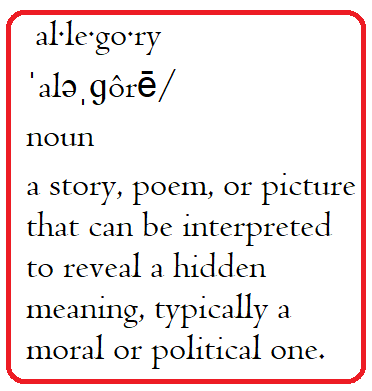

Allegory and symbolism are important tools in a writer’s toolbox. They are similar to each other but different and often misunderstood. The difference between them is in how they are presented.

- An allegory is a narrative, a moral lesson in the form of a story, heavy with symbolism.

- Symbolism is a literary device that uses one thing (an item, a theme, a visual reference, etc.) throughout the narrative to represent something else or to create an atmosphere and mood.

Using these tools in worldbuilding offers us a way to avoid clumsy info dumps to imply a particular atmosphere, underscoring a theme. We can increase the reader’s awareness of possible danger if that is our desire. It involves placing symbolism into the story’s visual environment.

Using these tools in worldbuilding offers us a way to avoid clumsy info dumps to imply a particular atmosphere, underscoring a theme. We can increase the reader’s awareness of possible danger if that is our desire. It involves placing symbolism into the story’s visual environment.

Symbolism helps create mood and atmosphere with fewer words. When certain objects are part of the world, what the characters see, hear, and smell is subliminal to the reader. But these clues evoke an emotional response in the reader, encouraging them to stay with the story.

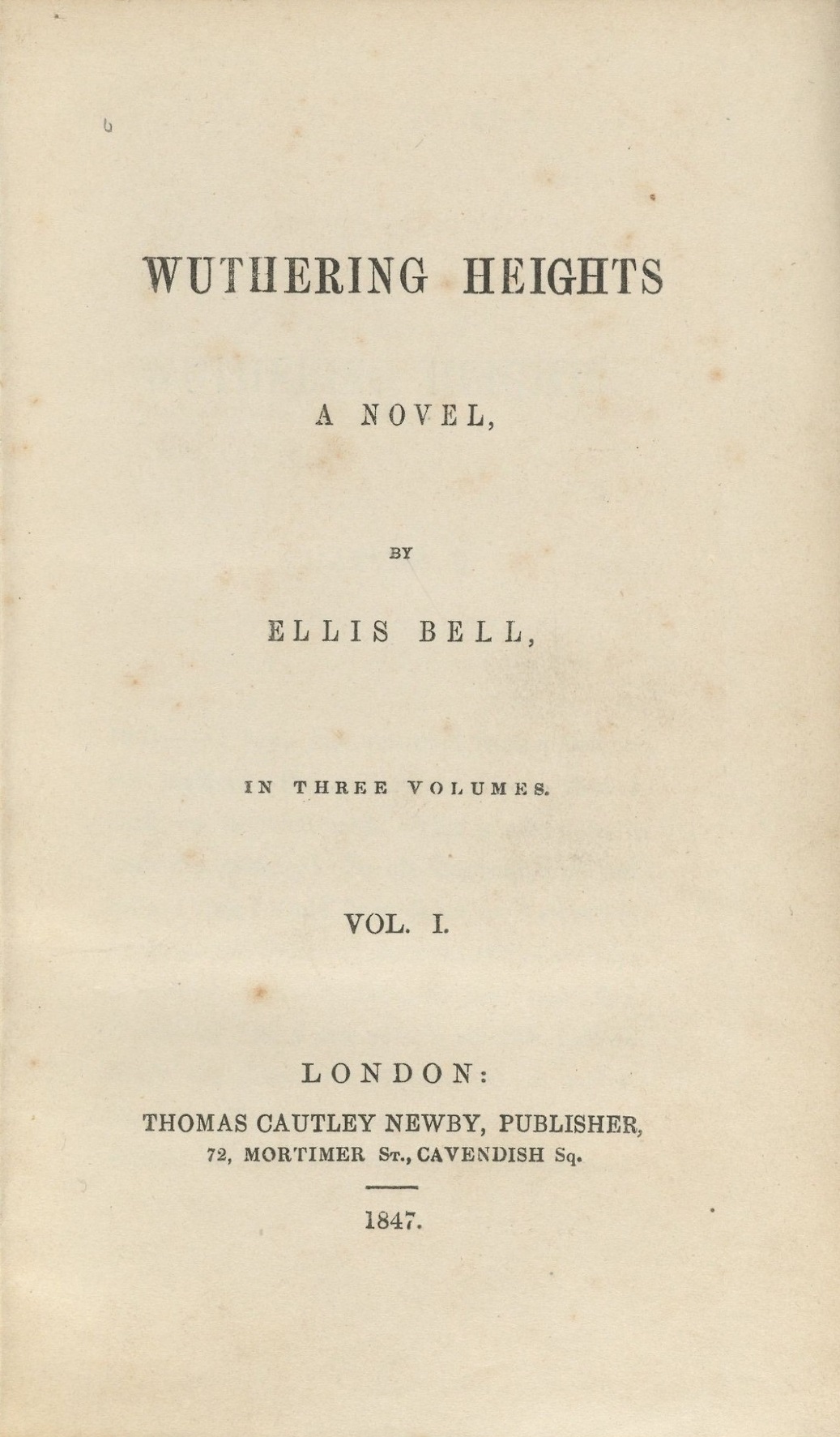

Take the classic Gothic novel Wuthering Heights. Interest in Emily Brontë’s work has never been greater, with a new movie based on the novel’s characters and setting.

Take the classic Gothic novel Wuthering Heights. Interest in Emily Brontë’s work has never been greater, with a new movie based on the novel’s characters and setting.

The movie strays widely from the novel. The novel is a tragedy delving into deeply disturbed personalities more than it is a romance.

It’s not an allegory because it doesn’t explore a moral or symbolic meaning beyond its obvious story. Brontë’s symbolism in her world-building supports and underscores the themes of love, revenge, and social class.

The way Emily Brontë employed atmosphere in Wuthering Heights is stellar. I would love to achieve that level of world-building.

We can find allegories in nearly any written narrative because humans love making connections and often imagine them where none exist. While Wuthering Heights is not considered an allegory in the literary sense, it is heavily symbolic.

Spark Notes says:

The constant emphasis on landscape within the text of Wuthering Heights endows the setting with symbolic importance. This landscape is comprised primarily of moors: wide, wild expanses, high but somewhat soggy, and thus infertile. Moorland cannot be cultivated, and its uniformity makes navigation difficult. It features particularly waterlogged patches in which people could potentially drown. (This possibility is mentioned several times in Wuthering Heights.) Thus, the moors serve very well as symbols of the wild threat posed by nature. As the setting for the beginnings of Catherine and Heathcliff’s bond (the two play on the moors during childhood), the moorland transfers its symbolic associations onto the love affair.

The two large estates within the book create a pocket world of sorts, where little, if anything, lies beyond their existence. Thus, windows both literal and figurative serve to showcase what exists on the other side while still keeping the characters trapped. [1] Wuthering Heights: Symbols | SparkNotes

Symbolism on its own is a powerful tool. We can show more with fewer words. But while a tale may be heavily layered with symbolism, it might not be an allegory.

So, what is an allegory?

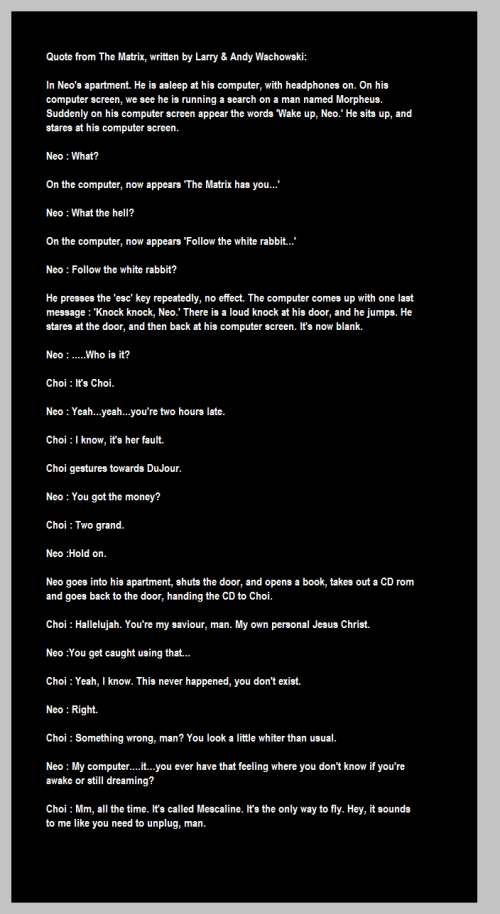

The storytelling in The Matrix series of movies is a brilliant example of an allegory. The Matrix was written by The Wachowskis. The narrative is an allegory for Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, a depiction of reality and illusion. The movies in the series employ heavy symbolism in both the setting and conversations to drive home the multilayered themes of humankind, machine, fate, and free will.

The storytelling in The Matrix series of movies is a brilliant example of an allegory. The Matrix was written by The Wachowskis. The narrative is an allegory for Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, a depiction of reality and illusion. The movies in the series employ heavy symbolism in both the setting and conversations to drive home the multilayered themes of humankind, machine, fate, and free will.

In The Matrix, reality and illusion are portrayed with layers of symbolism:

- The names of the characters

- The words used in conversations

- The androgynous clothes they wear

Everything on the set or mentioned in conversations underscores those themes, including the lighting. Inside The Matrix, the world is bathed in a green light, as if through a green-tinted lens. In the real world, the lighting is harsher, unfiltered.

Everything that appears or is said onscreen in the movie is symbolic and supports one of the underlying concepts. When Morpheus later asks Neo to choose between a red pill and a blue pill, he essentially offers the choice between fate and free will.

We incorporate symbolism and allegory into the environment during worldbuilding to create mood and atmosphere.

These subliminal impressions affect our (the reader’s) mood and emotions, drawing us deeper into that world. These are separate but entwined forces, and they can create an emotion in the reader, such as a sense of foreboding, which is a subtler form of foreshadowing.

In real life, emotion is the experience of contrast, of transitioning from negative to positive emotional energy, and back again.

In a powerful story, symbolism, allegory, or both exist on the surface and in the subtext. Without the feelings and emotions the writer injects into the story, our characters do a zombie-like shuffle to the end, leaving the reader feeling robbed.

Setting is only a place. It is not atmosphere. Mood, atmosphere, and emotion are part of the inferential layer of a story.

How a setting is shown contributes to the atmosphere. Atmosphere is created as much by odors, scents, ambient sounds, and visuals as by the characters’ moods and emotions. Emily Brontë‘s moors and windows are subliminal background elements, but they are also foreshadowing. They convey information to the reader on a subconscious level, supporting the actions and conversations of her characters.

In my own work, I want to convey mood and atmosphere without resorting to an info dump. But what symbols can I place in the environment of my current work-in-progress to help build suspense? I need to create a list and add it to my outline as I go.

In my own work, I want to convey mood and atmosphere without resorting to an info dump. But what symbols can I place in the environment of my current work-in-progress to help build suspense? I need to create a list and add it to my outline as I go.

- Side note: Just because I use a plan doesn’t mean you have to. It’s just how I work.

For me, themes are important, and a powerful theme inspires me to tell a story. A strong theme can offer suggestions and symbols when we imagine the world we are creating. I note these ideas in the outline, so I don’t lose track of them.

- Another side note: Don’t be surprised if a casual reader doesn’t notice the symbolism you worked so hard on. They won’t see symbolism on a conscious level. However, it will reinforce the mood and atmosphere, keeping them reading.

Dedicated readers love work that holds up on closer examination, enjoying work with layers of depth, work they can read again and again and always find something new in it.

On the surface, the story and the characters who live it out are what make a book great. Deeper down, the allegories and symbolisms embedded in the narrative sink into the reader’s subconscious, stirring thoughts and raising ideas they might not otherwise have considered.

On the surface, the story and the characters who live it out are what make a book great. Deeper down, the allegories and symbolisms embedded in the narrative sink into the reader’s subconscious, stirring thoughts and raising ideas they might not otherwise have considered.

Previous in this series: Revisions, part 1: Shakespeare and the Art of Foreshadowing #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Wuthering Heights: Symbols | SparkNotes Copyright ©2026SparkNotes LLC (accessed 08 February 2026). Fair Use.