Good foreshadowing is crucial. If, like me, you work from an outline (a planner), you might plan to embed clues in the first quarter of the story, hints that are little warning signs of future events. For those who wing it (pantsers), this happens on a subconscious level, but it does happen.

For those who wing it (pantsers), this happens on a subconscious level, but it does happen.

Whether we are planners or pantsers, clumsy foreshadowing or neglecting to foreshadow are things we do when laying down our story’s first draft.

They are clues we leave in our first drafts, hints that tell us what we need to expand on or cut. For new writers, recognizing and correcting those signals can be a challenge. Experience helps us understand what we are looking at when it comes to seeing our own work with an unbiased eye.

- Writing as often as we can, daily if possible.

- Attending writing seminars.

- Reading books on the craft.

- Participating in local writing groups.

- Looking back at our earlier work with a critical eye.

Foreshadowing can be an opportunity for an info dump. This is why we seek out writing groups or hire freelance editors. We want our work to be the best we can make it. And trust me, first drafts are rife with what doesn’t work as it is currently written.

Even editors have editors because when it comes to our own work, we see what we intended to write, not what is there.

- Running it through ChatGPT isn’t having it edited

- Nor is running it through Grammarly or ProWriting Aid, or any other editing software.

Absolute perfection is flat and mechanical, devoid of life. The eye of an experienced editor is needed to ensure the human element, the voice of the author, is protected and developed in a manuscript.

The second draft is when we finetune our foreshadowing. When a possibility is briefly, almost offhandedly mentioned, but almost immediately overlooked or ignored by the protagonists, that is foreshadowing.

It is perfectly acceptable to use the occasional “I told you so” moment in fiction. These happen in real life, but fiction isn’t quite real. ALL fiction is a way of dealing with reality but dressed up in a bit of fantasy.

We subtly insert small hints, little offhand references to future events. If the narrative is well-written, readers will stick with it as they will want to see how it plays out.

Readers aren’t perfect. Some will miss the suggested possibility just as the unsuspecting characters do. Other readers will catch the clues and begin to worry.

The most crucial aspect of foreshadowing is the surprise when all the pieces fall into place. This is the moment when the reader says, “I should have seen that coming.”

We have many reasons to pursue good foreshadowing skills. In my opinion, the most important is that it helps avoid using the clumsy Deus Ex Machina (pronounced: Day-us ex Mah-kee-nah) (God from the Machine) as a way to miraculously resolve an issue.

We have many reasons to pursue good foreshadowing skills. In my opinion, the most important is that it helps avoid using the clumsy Deus Ex Machina (pronounced: Day-us ex Mah-kee-nah) (God from the Machine) as a way to miraculously resolve an issue.

A Deus Ex Machina occurs when, toward the end of the narrative, an author inserts a new event, character, ability, or otherwise resolves a seemingly insoluble problem in a sudden, unexpected way.

Foreshadowing also helps us avoid the opposite and equally awkward device, the Diabolus Ex Machina (Demon from the machine). This is the bad guy’s counterpart to the Deus Ex Machina.

It’s a problem that occurs when the author suddenly realizes the evil his character faces doesn’t warrant a novel. Yet, they don’t want to waste what they have already written. At that point, they introduce an unexplained new event, character, ability, or object designed to ensure things suddenly get much worse for the protagonists.

As a reader, I hate it when a character suddenly develops a new skill or knowledge without explanation. This is when the narrative becomes unbelievable and is known as a Chekhov’s Skill. Some authors explain it away after the fact, but this kind of fault makes it impossible for me to suspend my disbelief. To avoid this, we need to mention previous examples of the characters using or training that skill. Without briefly foreshadowing that ability, the reader will assume the character doesn’t have it.

Literature and the expectations of the reader are like everything else. They evolve and change over the centuries.

In genre fiction today, a prologue may or may not be a place for foreshadowing. This is because modern readers don’t have the patience to wade through large chunks of exposition dumped in the first pages of a novel.

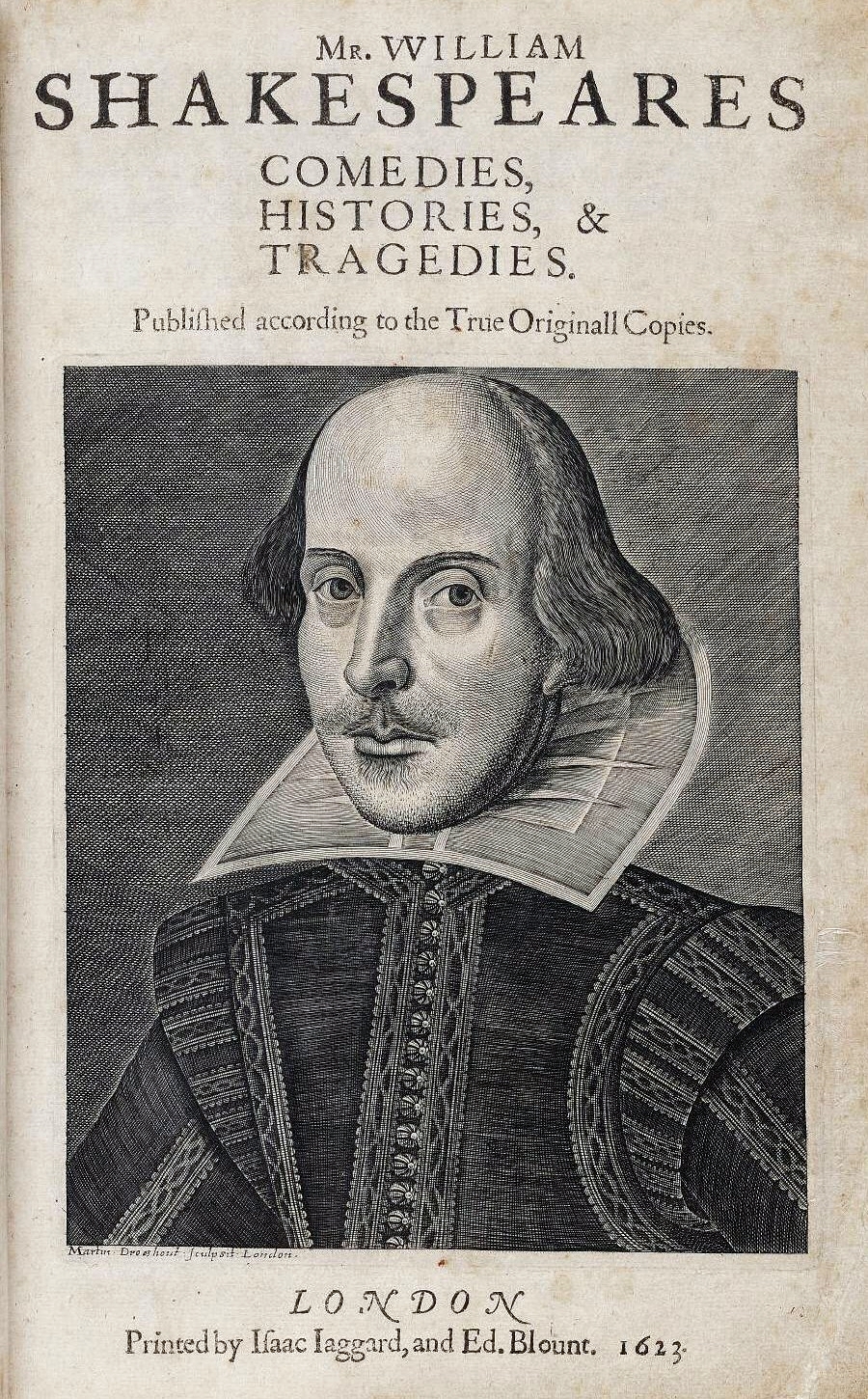

William Shakespeare used both exposition and foreshadowing. Larger events may be foreshadowed through the smaller events that precede them.

Let’s look at a scene from The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, one I have talked about before. Modern readers know it as simply Romeo and Juliet, but Shakespeare originally called it what it is: a tragedy. This is the scene where Benvolio is trying to talk Romeo out of his infatuation for Rosaline.

Let’s look at a scene from The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, one I have talked about before. Modern readers know it as simply Romeo and Juliet, but Shakespeare originally called it what it is: a tragedy. This is the scene where Benvolio is trying to talk Romeo out of his infatuation for Rosaline.

“Take thou some new infection to thy eye,

And the rank poison of the old will die.”

In other words, “Dude, the minute you see a new girl, you’ll forget this one.”

Benvolio knows his friend well. Just as he predicts, as soon as Romeo lays eyes on Juliet, he forgets his obsession with Rosaline, and a new obsession begins.

Shakespeare employs foreshadowing again in a later scene. When Benvolio brings the news that Mercutio is dead, Romeo says,

“This day’s black fate on more days doth depend;

This but begins the woe, others must end.”

Romeo is predicting that Mercutio’s death is a disaster for everyone and feels as if he is racing toward an unknown future.

In that moment, we see that Romeo is deeply aware that he has reached a point of no return.

He must fight Tybalt to avenge Mercutio because his society requires it. Therefore, he must duel to the death despite knowing that killing Tybalt won’t resolve anything. Instead, the murder will only perpetuate the problem.

Romeo has seen the foreshadowing and knows he is no longer in control of his fate.

This is one of the many reasons why (four-hundred years later) we still read and love the works of William Shakespeare. This is why movies about him are still being made, such as 2025’s masterpiece, Hamnet.

It takes both restraint and skill to insert tiny hints of what is to come into your narrative, but foreshadowing gives the protagonists (and the writer) an indication of where to go next.

These clues tantalize a reader. The desire to see if what we think has been foreshadowed keeps us turning the page.

Part 2 of this little series on revisions will explore worldbuilding and how the clues we leave in the environment can be a form of foreshadowing. And later, we will talk about easy fixes for those of us whose schooldays didn’t include a dive into practical grammar.