Every now and then, one of the forums I visit will have a group of people engaged in a little gripe session, sparking a series of comments on how English seems to be sliding in a new and degenerate direction.

I’ve said it before, and I will say it again: English is the ever-disintegrating language. The very roots of English encourage its continual evolution, and the advent of smartphones and the internet have this rollercoaster hurtling downhill.

I’ve said it before, and I will say it again: English is the ever-disintegrating language. The very roots of English encourage its continual evolution, and the advent of smartphones and the internet have this rollercoaster hurtling downhill.

Unfortunately, I love how each generation of the last three hundred years has twisted common words and used them in “wrong” ways. (I know, I’m naughty.)

The problem many writers have is not with the words they choose and use. It is the lack of knowledge where grammar and sentence structure are concerned.

The problem many writers have is not with the words they choose and use. It is the lack of knowledge where grammar and sentence structure are concerned.

English grammar, and punctuation in particular, is designed to meet a reader’s expectations. This means that punctuation isn’t flexible, but many other aspects of grammar are.

What makes grammar confusing to the inexperienced author is the fact that the rules are bursting at the seams with exceptions.

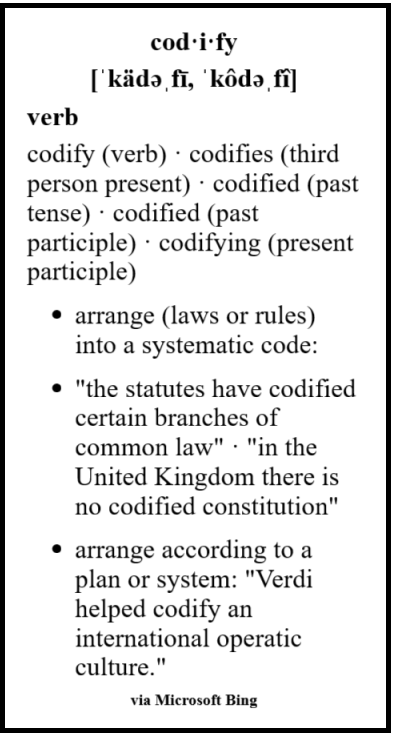

This is because, a long time ago in a university far, far away, a bunch of smart guys in Victorian England decided to codify the slippery eel that is English.

They applied the rules of a dead language, Latin, to an evolving language with completely different roots, Frisian smushed together with Old French, and added a bunch of mish-mash words and usages invented by William Shakespeare, calling it “Grammar.”

Some writers are grumpier than others. They do make me laugh, though, with their diatribes declaring that certain newer word usages either signify lazy speech habits or a shift in the language.

A long time ago, I came up with a short list of text-message words that have bled into daily usage. These magical morsels of madness are only the tip of the pox-ridden iceberg:

Supposably … one of my personal favorite crutch words. You may ask if I meant supposedly, and I will look at you with a blank stare.

Liberry … unfortunately, you must go to the library for those books. The liberry will give you hives.

Feberry ... I hope you mean it will happen in February, because Feberry will never come.

Honestness... honestly, I’m not sure what to make of that one.

But my particular favorite is prolly, which my granddaughters think means probably, but in all honestness, doesn’t. Although in fifty years, it may be the preferred form in the dictionary, and the word probably will be cited as the archaic form.

But my particular favorite is prolly, which my granddaughters think means probably, but in all honestness, doesn’t. Although in fifty years, it may be the preferred form in the dictionary, and the word probably will be cited as the archaic form.

It’s not a new problem. Jonathan Swift, writer and dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, went so far as to say, “In many Instances, it offends against every Part of Grammar.”

Well, that is prolly a little harsh.

English shifts a little with every passing year. It seeks out and pools up in the lowest places. It steals what it wants from every other language it comes across.

That is what makes it so fun to play with. And it’s also what makes English so difficult to work with.

That is what makes it so fun to play with. And it’s also what makes English so difficult to work with.

The real problem with some novels, as I see it, isn’t mangled words. It’s this: proper punctuation is vital for the reader to understand and enjoy what you have written.

Punctuation acts as traffic signals, regulating the flow of words in such a way that the reader doesn’t realize it’s there. Instead, they are completely involved in the book.

You don’t have to invest in a library of books on style and writing (even though I can’t pass them up). I have done the work for you by condensing basic punctuation into seven painless rules in this article from last May. It should get you on the right path, punctuation-wise. https://conniejjasperson.com/2025/05/26/self-editing-part-one-7-easy-to-remember-rules-of-punctuation-writing/

An author’s personal voice and style affect the overall readability of their finished product. Good readability is achieved by authors who have developed three traits: understanding of the craft, a touch of rebellion, and wordcraft.

- Understanding of the craft: Readers expect certain things of prose, things that go beyond the author’s voice and style. I suggest keeping to generally accepted grammatical practices when constructing sentences. Consider purchasing and using a style guide. This is handy to have when questions arise.

- Rebellion: We love it when authors successfully choose to break the accepted rules. They are successful because they do so in a consistent manner, and the reader becomes used to it.

- Wordcraft: The way the author phrases things, and the words he/she chooses, combined with his/her knowledge of the language and accepted usage. Perhaps they aren’t afraid to use invented word combinations, such as wordcraft (word+craft). They deliberately choose the context in which their words are placed.

Simply having a unique style does not make your work fun to read. You must meet the reader’s expectations regarding sentence construction, or they will become confused and put the book down. If they review it, they won’t be kind. “Did not finish” is not a good review.

As you are developing your style, remember: we want to challenge our readers, but not so much that they put our work down out of frustration.

As you are developing your style, remember: we want to challenge our readers, but not so much that they put our work down out of frustration.

Most Indies can’t rely on their names to sell books. That requires marketing, a can of worms I am not qualified to open. But I do know this: there is no point in spending the time and money trying to market a book rife with errors and garbled sentences.

What you choose to write and how you write it is like a fingerprint. It will change and mature as you grow in your craft, but it will always be recognizably yours.