I often find myself writing short pieces. These are scenes and mini stories that don’t really fit into a novel but are on my creative mind. Writing a short story gives me the chance to explore an idea that might be inspired by my longer work, but would muddy the waters if I included it there.

Many of my works are series, each set in a world of my creation. Writing short stories helps me develop that world. As a side benefit, it develops characters and plots I will definitely use later.

Many of my works are series, each set in a world of my creation. Writing short stories helps me develop that world. As a side benefit, it develops characters and plots I will definitely use later.

But what about stand-alone short stories? I usually submit them to contests, online magazines, and themed anthologies. The editor of the anthology ensures that each story she accepts explores an aspect of a single unifying theme.

And truthfully, having a theme to write to kickstarts my imagination.

According to Wikipedia:

A theme is not the same as the subject of a work. For example, the subject of Star Wars is ‘the battle for control of the galaxy between the Galactic Empire and the Rebel Alliance.’

The themes explored in the films might be “moral ambiguity” or “the conflict between technology and nature.” [1]

When we submit our manuscript to an editor with an open call for themed work, we must demonstrate our understanding of how the central theme can be manipulated to tell a story. Of course, engaging prose and a unique voice make a story stand out.

When you plan a story, analyze the theme. Look beyond the obvious tropes and find an original angle, and then go for it. As an author, most of my novels have been epic or medieval fantasy, based around the hero’s journey, detailing how their experiences shape the characters’ reactions and personal growth.

When you plan a story, analyze the theme. Look beyond the obvious tropes and find an original angle, and then go for it. As an author, most of my novels have been epic or medieval fantasy, based around the hero’s journey, detailing how their experiences shape the characters’ reactions and personal growth.

The hero’s journey is a theme that allows me to employ the sub-themes of brother/sisterhood and love of family.

Other layers of the story are strengthened when supported by a strong theme. Subtle use of allegory and imagery in set dressing can help strengthen the theme without beating the reader over the head.

In a story, the theme is introduced, either subtly or overtly, at the first plot point. If we’re writing a short story, this must happen on the first page. Most open calls for short stories require us to meet a specific word count. If so, lengthy lead-ins are not possible, as manuscripts that exceed the word count will be rejected.

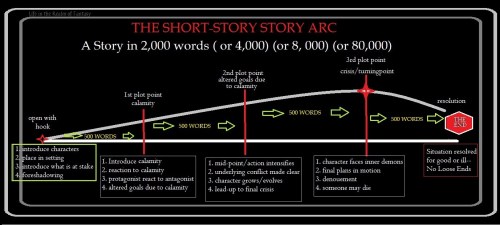

I find it is easier to meet that wordcount when I know in advance how a story will end. I am a linear thinker, so I make an outline of my intended story arc.

- I am an outliner, a planner, because when I “pants” it, I end up with a mushy plot that wanders all over the place and a story that isn’t commercially viable.

To create my outline, I divide my story arc into quarters. This ensures the critical events are in place at the right time. Then, I ask myself several questions about the story as I first imagine it. This will evolve, but it offers my creative mind a jumping off point.

- What is the inciting incident? How does it relate to the theme?

- What is the goal/objective? How does it relate to the theme?

- At the beginning of the story, what does the hero want so badly that she will risk everything to acquire it? Why?

- Who is the antagonist? What do they want and why?

- What moral (or immoral) choice will our hero have to make? This is the real story, and how does it relate to the theme?

- What is happening at the midpoint? Why does the antagonist have the upper hand?

- At the ¾ point, my protagonist should have gathered her resources and be ready to face the antagonist. How can I choreograph that meeting?

- How does the underlying theme affect every aspect of the protagonists’ evolution in this story?

I have mentioned before that in my own writing life, dumping too much background is my greatest first-draft challenge. Writing short stories has helped me find ways to write more concisely.

I have mentioned before that in my own writing life, dumping too much background is my greatest first-draft challenge. Writing short stories has helped me find ways to write more concisely.

An outline keeps me on track. What is essential for the reader to know, and when should they learn it? What is just info for me to cut and save in the outtakes file?

Short stories follow a single event in a character’s life. Each word must advance that one story thread. Having your work beta read by your critique group will help you identify those places that need to be trimmed down.

I have close friends who see my work first and who help me see what the real story is before I bother my editor with it. My beta readers are published authors in my writing group.

Because I am a wordy writer, I have to keep in mind that (especially in a short story) every word is precious and must be used to the greatest effect. By shaving away the unneeded info in the short story, I can expand on the theme of the story and how it drives the plot.

Credits and Attributions:

Wikipedia contributors, ‘Theme (arts),’ Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Theme_(arts)&oldid=848540721(accessed July 12, 2025).