Today, we’re continuing our Preptober series by designing a conflict and a story arc. I write fantasy, but every story is the same, no matter the set dressing. Protagonist A needs something desperately, and Antagonist B stands in their way.

What does the protagonist want? Everyone wants something. The story is in the way they fulfill that need, or what happens when they don’t. Doubt, uncertainty, people facing the unknown as they struggle to succeed in their quest … these nouns are what makes the story interesting.

What does the protagonist want? Everyone wants something. The story is in the way they fulfill that need, or what happens when they don’t. Doubt, uncertainty, people facing the unknown as they struggle to succeed in their quest … these nouns are what makes the story interesting.

This is where we have to sit and think a bit. Are we writing a murder mystery? A space-opera? A thriller? The story of a girl dealing with bulimia?

Let’s do something different and write a historical fiction.

My Uncle Don fought in WWII in the Ardennes and was wounded, coming home with a steel plate in his head. He was an unfailingly kind man who never discussed his wartime experiences. Here in the US, that battle is referred to as the Battle of the Bulge.

- Our proposed novel’s genre is historical fiction because it explores a fictional Allied soldier’s experiences. It isn’t a biography.

However, any historical fiction novel is a form of fantasy. This is because we must imagine how our soldier acted and reacted to the events, and the friends he made and lost along the way. Those events now exist only in a few places, such as military archives, old newspaper accounts, and the memories of a generation that is now in their nineties.

We will make a list of things we want to include in our worldbuilding. Filthy living conditions will provide the backdrop to the impending confrontation. Life on the frontline was brutal, and we need to use the environment to emphasize our characters’ experience of combat as it was in 1944-45.

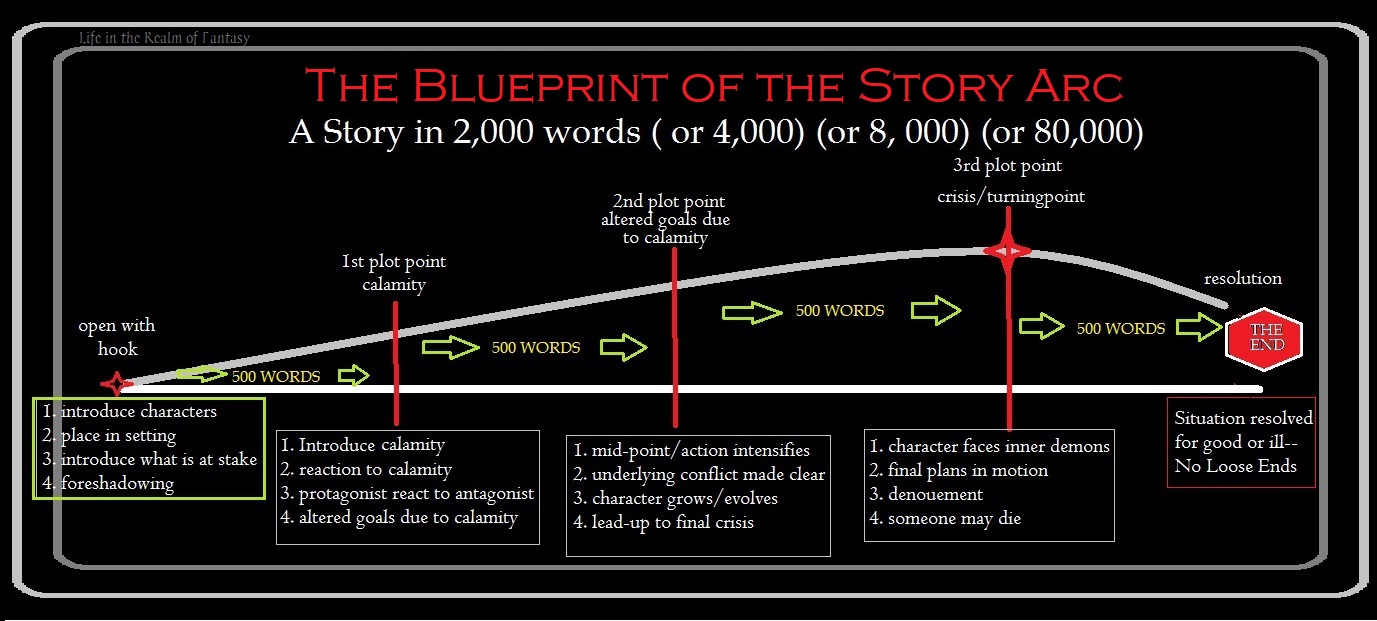

We want to have a complete story arc, so what length should our manuscript top out at? We will plan for a mid-length novel of 75,000 words. We get out the calculator and divide our word count by 4.

- The first quarter will be 18,175 words, the two middle quarters will be 37,500 words, and the final run-up to the climactic ending will be 18,175 words.

The first quarter opens our story and introduces the moment of no return, even if our characters still believe they can salvage things.

The first quarter opens our story and introduces the moment of no return, even if our characters still believe they can salvage things.

The following two quarters are the middle of the narrative, exploring the obstacles that our soldier faces. The final quarter winds our soldier’s story up.

- HINT: If you are writing a historical novel, your plot will follow the historical calendar of actual events. For our sample, the Battle of the Bulge was fought between 16 December 1944 and 25 January 1946. Reams of documentation still exist detailing that terrible month.

- 2nd HINT:our soldier will either be with the US 30th Infantry Division at the Battle for St. Vith (Americans) or the Meuse River bridges (British 29th Armoured Brigade of 11th Armoured Division).

Remember, the historical events are NOT movable or changeable if you want to remain in the historical fiction genre. Once you change the timeline or alter events in any way, you have ventured into alternate history and are writing speculative fiction.

I confess, spec-fic is my kind of book. But accuracy counts for readers of historical fiction.

Readers are smart. Military buffs will know that a soldier can’t be at both St. Vith and the Meuse River, unless he was in the US Army Air Force.

So, our four quarters can be divided this way if our soldier is American:

- Attack in the south

- Allied counteroffensive

- German counterattack

- Allies prevail

We will write the scenes that connect those events, and that is where we take a deep dive into history. We can invent characters and use our imagination to flesh out their lives within as accurate a WWII context as possible.

To complete our story arc, we will

- Take each incident and write the scenes that our soldier experiences.

- We might also write scenes showing the commanders planning the offensives and switch to show the enemy’s plans.

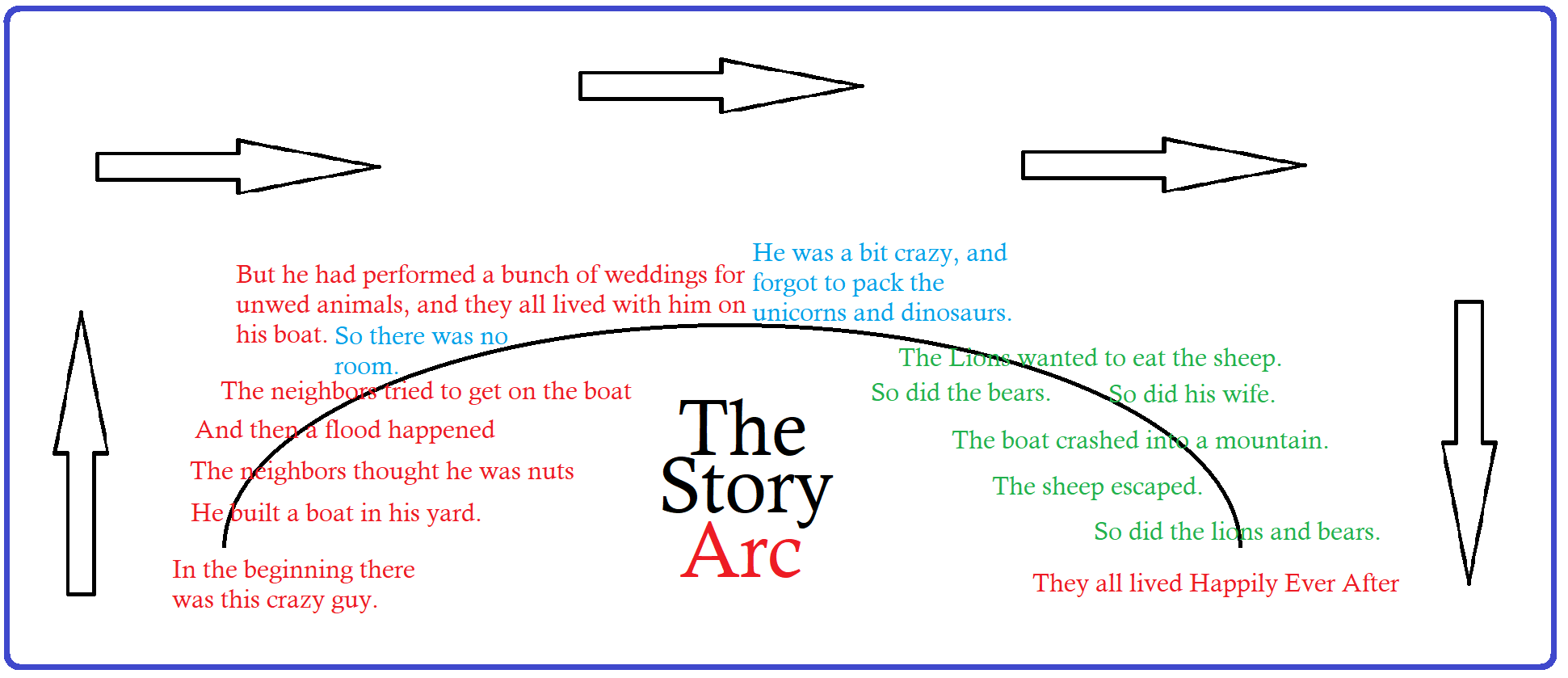

No matter what genre of book you plan to write, all you need is a skeleton of the plot, just a series of events for you to connect. You will write the scenes between these events, connecting them to form a story with an arc to it.

No matter what genre of book you plan to write, all you need is a skeleton of the plot, just a series of events for you to connect. You will write the scenes between these events, connecting them to form a story with an arc to it.

As we write, our soldier’s thoughts and interactions will illuminate and color the scenes. His encounters, how he saw the enemy. Were they people like him or were they faceless? All his emotions will emerge as you write his story.

But maybe you aren’t writing a historical fiction. Some things are universal.

No matter what genre we are writing in, we start with a worthy problem, a test that will propel the protagonist to the middle of the book.

This event is the inciting incident and could be the hook. We discover a problem and set our heroine on the trail of the answer. In finding that answer, she is thrown into the action.

Drop the protagonist into the action as soon as possible, even if the conflict is interpersonal. It could be a minor hiccup that spirals out of control with each attempt to resolve it.

- This is the place where the characters are set on the path to their destiny.

Some plots are action and adventure. Other books explore a relationship that changes a character’s life in one direction or another. Others, like our war story, explore surviving extreme hardship.

The inciting incident is the moment when the protagonists first realize they’re utterly blocked from achieving their desired goal. Note this event on your outline early in the first quarter. Then the trouble escalates, so make a note of the moment our protagonist realizes their situation is much worse than they initially thought.

At this point, our people have little information regarding the magnitude of their problem. One thing that I do is make notes that help limit my tendency toward heavy-handed foreshadowing. Most of what I write in the first draft will be severely cut back by the time I’m done with the final revisions.

Subplots will emerge once I begin writing. I note them on the outline as soon as I can, but sometimes I do forget.

The last weeks of Preptober are upon us and this is a good time to visit the brick-and-mortar bookstore and look at the books currently being offered in the genre you are writing in. Then you’ll know what you need to achieve in your work if you want to sell that story.

Every year I participate in

Every year I participate in  Who are the players?

Who are the players? Characters usually arrive in my imagination as new acquaintances inhabiting a specific environment. That world determines the genre.

Characters usually arrive in my imagination as new acquaintances inhabiting a specific environment. That world determines the genre. Today, we continue that discussion with four more genres, each with many subgenres. First up is westerns. This is a popular genre with several common tropes and can be tricky to write respectfully and find a publisher for.

Today, we continue that discussion with four more genres, each with many subgenres. First up is westerns. This is a popular genre with several common tropes and can be tricky to write respectfully and find a publisher for. However, more and more, we are finding stories with female protagonists. An excellent example of this is the novel,

However, more and more, we are finding stories with female protagonists. An excellent example of this is the novel,  The Agatha Christie / Sherlock Holmes style of novel is the classic whodunnit. They feature a private detective with close ties to law enforcement but who is still an outsider. The detective sometimes has a sidekick who chronicles their cases. At times, the detectives butt heads with the police as resentment of the protagonist’s stepping on their turf crops up. This jealousy hinders the investigation. Clues are always inserted so that the reader doesn’t notice them until the denouement, and the sidekick never guesses right either.

The Agatha Christie / Sherlock Holmes style of novel is the classic whodunnit. They feature a private detective with close ties to law enforcement but who is still an outsider. The detective sometimes has a sidekick who chronicles their cases. At times, the detectives butt heads with the police as resentment of the protagonist’s stepping on their turf crops up. This jealousy hinders the investigation. Clues are always inserted so that the reader doesn’t notice them until the denouement, and the sidekick never guesses right either. Definitions differ as to what constitutes a historical novel. On the one hand, the

Definitions differ as to what constitutes a historical novel. On the one hand, the  To know that, you must know the genre of the work you are trying to sell. So, what exactly are genres? Publisher and author

To know that, you must know the genre of the work you are trying to sell. So, what exactly are genres? Publisher and author  Mainstream (general) fiction—Mainstream fiction is a general term that publishers and booksellers use to describe works that may appeal to the broadest range of readers and have some likelihood of commercial success. Mainstream authors often blend genre fiction practices with techniques considered unique to literary fiction. It will be both plot- and character-driven and may have a style of narrative that is not as lean as modern genre fiction but is not too stylistic either. The novel’s prose will at times delve into a more literary vein than genre fiction. The story will be driven by the events and actions that force the characters to grow.

Mainstream (general) fiction—Mainstream fiction is a general term that publishers and booksellers use to describe works that may appeal to the broadest range of readers and have some likelihood of commercial success. Mainstream authors often blend genre fiction practices with techniques considered unique to literary fiction. It will be both plot- and character-driven and may have a style of narrative that is not as lean as modern genre fiction but is not too stylistic either. The novel’s prose will at times delve into a more literary vein than genre fiction. The story will be driven by the events and actions that force the characters to grow. Fantasy is a fiction genre that commonly uses magic and other supernatural phenomena as a primary plot element, theme, or setting. Like sci-fi and literary fiction, fantasy has its share of snobs when it comes to defining the sub-genres. The tropes are:

Fantasy is a fiction genre that commonly uses magic and other supernatural phenomena as a primary plot element, theme, or setting. Like sci-fi and literary fiction, fantasy has its share of snobs when it comes to defining the sub-genres. The tropes are: Literary fiction can be adventurous with the narrative. The style of the prose has prominence and may be experimental, requiring the reader to go over certain passages more than once. Stylistic writing, heavy use of allegory, the deep exploration of themes and ideas form the core of the piece.

Literary fiction can be adventurous with the narrative. The style of the prose has prominence and may be experimental, requiring the reader to go over certain passages more than once. Stylistic writing, heavy use of allegory, the deep exploration of themes and ideas form the core of the piece.