I do a lot of rambling in my first drafts because I’m trying to visualize the story. While I try to write this mental blather in separate documents, the random thought processes often bleed over into my manuscript.

I do a lot of rambling in my first drafts because I’m trying to visualize the story. While I try to write this mental blather in separate documents, the random thought processes often bleed over into my manuscript.

During the editing process, I sometimes find that besides the four chapters that don’t fit the plot anymore, perhaps three more chapters will expand on background info. They can be condensed or cut.

I’m a wordy writer, but sometimes the finished work is shorter than I’d planned—a lot shorter. Sometimes, I get to the end of a story, but it’s only at the 40,000-word mark (or less).

Then I have to make a decision. I could choose to leave it at the length it is now and have it edited. If I am married to the idea of a novel, I could try to stretch the length, but why?

If I know anything, it’s this. When I have nothing of value to add to the tale, it’s best to stop. Fluff weakens the story, and I’d prefer to write a powerful novella rather than a weak novel.

In the second draft of any manuscript, I change verbs to be more active and hunt for unnecessary repetitions of information. At that stage, the manuscript will expand and contract. It hurts the novelist in my soul, but the story may only be 35,000 words long when the second draft is complete.

40,000 words in fantasy is less than half a book. That makes it a novella. But I send it to my beta reader to see what she thinks. If she feels the plot lacks substance at that length, I let it rest for a while, then come back to it. Then, I can see where to add new scenes, events, and conversations to round out the story arc. That might bring it up to the 60,000-word mark.

40,000 words in fantasy is less than half a book. That makes it a novella. But I send it to my beta reader to see what she thinks. If she feels the plot lacks substance at that length, I let it rest for a while, then come back to it. Then, I can see where to add new scenes, events, and conversations to round out the story arc. That might bring it up to the 60,000-word mark.

If Sherrie (my sister and beta reader) says the story is good and ends well, I stop adding content and move to the editing process.

So, what sort of scenes do I cut?

A detailed history of everyone’s background is unnecessary. Readers only want to hear a brief mention of historical information. It should be delivered in conversation and only when the protagonist needs to know it.

Unfortunately, when I am building the basic structure of the novel, I sometimes forget to write the cast members’ history in a separate document. Once I shrink or cut those rambling paragraphs, I have a scene that moves the story forward but is much shorter.

In the second draft, I will discover passages where I have repeated myself but with slightly different phrasing. My editor is brilliant at spotting these, which is good because I miss plenty of them when I am preparing my manuscript for editing. I wrote that mess, so even though I try to be vigilant, repetitions tend to blend into the scenery.

In the second draft, I will discover passages where I have repeated myself but with slightly different phrasing. My editor is brilliant at spotting these, which is good because I miss plenty of them when I am preparing my manuscript for editing. I wrote that mess, so even though I try to be vigilant, repetitions tend to blend into the scenery.

Once Irene points them out, I decide which wording I like the best and go with that.

Also, in the first draft, I find a lot of “telling” words and phrases I will later change or cut. I look for active alternatives for words and phrases that weaken the narrative:

- There was

- To be

I change my weak, telling sentences to more active phrasing. This means I sometimes gain a few words because showing a scene as it happens requires more words than giving a brief “they did this.”

But then I lose words in other areas—lots of words.

I feel that when writing in English, the use of contractions makes conversations feel more natural and less formal. It shortens the word count because two words become one: was not is shortened to wasn’t, has not is changed to hasn’t, etc.

Reading my manuscript out loud is a real eye-opener. I print each chapter out and read it aloud. I find words to cut, sentences and entire paragraphs that make no sense. The story is stronger without them.

In the first draft, I look for crutch words and remove them. This lowers my word count. My personal crutch words are overused words that fall out of my head along with the good stuff as I’m sailing along:

- So (my personal tic)

- Very (Be wary if you do a global search – don’t press “replace all” as most short words are components of larger words, and ‘very’ is no exception.)

- That

- Just

- Literally

I try to plot my books in advance, but my characters have agency. This means the character arcs and the story evolves as I write the first draft. New events emerge, and I find better ways to get to the end than what was first planned.

I have learned to be brutal. I might have spent days or even weeks writing a chapter that now must be cut.

I have learned to be brutal. I might have spent days or even weeks writing a chapter that now must be cut.

It hurts when a perfect chapter no longer fits the story. But maybe it bogs things down when you see it in the overall context. It must go, but that chapter will be saved. Those cut pieces often become the core of a new story, a better use for those characters and events.

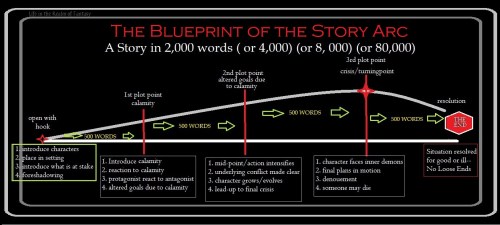

Once that first draft is complete, no matter how short or long, I measure it against the blueprint of the story arc. I ask the following questions about every story:

- How soon does my inciting incident occur? It should be near the front, as this will get the story going and keep the reader involved.

- How soon does the first pinch point occur? This roadblock will set the tone for the rest of the story.

- What is happening at the midpoint? Are the events of the middle section moving the protagonist toward their goal? Did the point of no return occur near or just after the midpoint?

- Where does the third pinch point occur? This event is often a catastrophe, a hint that the protagonist might fail.

- Is the ending solid, and does it resolve the major problems?

Even if this story is one part of a series, we who are passionate about the story we’re reading need firm endings.

Even if this story is one part of a series, we who are passionate about the story we’re reading need firm endings.

Novellas occupy a special place in my heart. A powerful, well-written novella can be a reading experience that shakes a reader’s world. The following is a list of my favorite novellas. And yes, you’ve seen this list before, and also yes, some are considered literary fiction:

The Emperor’s Soul, by Brandon Sanderson

The Emperor’s Soul, by Brandon Sanderson- A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens

- Breakfast at Tiffany’s, by Truman Capote

- Candide, by Voltaire

- Three Blind Mice, by Agatha Christie

- The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Robert Louis Stevenson

- The Time Machine, by H.G. Wells

- Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck

- The Old Man and the Sea, by Ernest Hemingway

- Animal Farm, by George Orwell

- The Turn of the Screw, by Henry James

Read.

Read widely and try to identify the tricks that impressed you. The real trick is figuring out how to put what you learn to good use.

In some circles, 40,000 words is a novel, but in fantasy, it is less than half a book.

In some circles, 40,000 words is a novel, but in fantasy, it is less than half a book. A detailed history of everyone’s background isn’t required. As a reader, all we need is a brief mention of historical information in conversation and delivered only when the protagonist needs to know it.

A detailed history of everyone’s background isn’t required. As a reader, all we need is a brief mention of historical information in conversation and delivered only when the protagonist needs to know it.