We often talk about the story arc and its component parts and features. But to explain depth, we must put all the parts and pieces back together and examine the story as a whole.

So, what is depth, exactly? It is the component of the narrative that supports and informs the story’s arc. It is also comprised of layers.

So, what is depth, exactly? It is the component of the narrative that supports and informs the story’s arc. It is also comprised of layers.

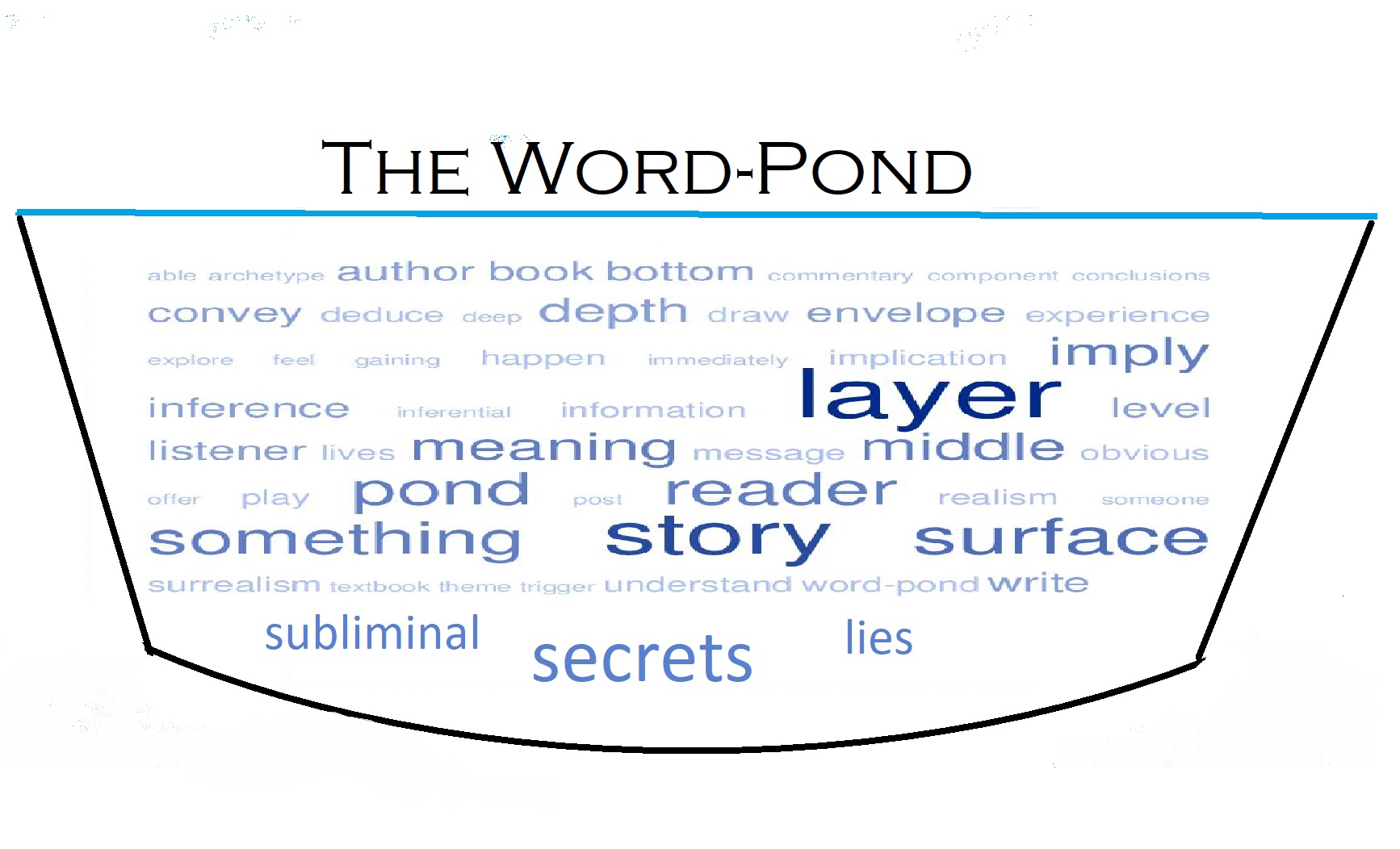

When you look at a pond, you see the surface. It could be calm, or if a storm is brewing, it will be ruffled and moving. But it is deep and conceals many things beneath that calm surface. A narrative also comprises several layers.

Layer One is the surface layer. It is the Literal Layer; the what-you-see-is-what-you-get layer. The components of the story’s surface are:

- the setting

- the action

- the visual/physical experience of the characters as they go about their lives.

When the reader sees something, they recognize it. Trees are trees, a bus is a bus, and we all recognize those aspects of worldbuilding. The surface layer also shows the characters’ actions in real time, so readers immediately feel they know what is going on.

The reader sees it when a figure steps from behind a tree. A gun was drawn and fired. What happened was clear and easy to understand.

The reader sees it when a figure steps from behind a tree. A gun was drawn and fired. What happened was clear and easy to understand.

Some authors play with the surface layer, choosing realism, surrealism, or a blend of the two.

- Realism is serious, a depiction of what undisputedly is.

- Surrealism takes what is real and warps it to convey a subtler meaning.

Layer Two: The layer below the surface is an area of unknown quantity. It is the Inferential Layer. This is the layer where inference and implication come into play, hints and allegations.

We show why the gun is drawn. Clues and hints imply reasons for the characters’ actions. The author offers ideas to explain how the shooter arrives at the point in the story where they squeeze the trigger, and the reader makes assumptions.

Authors drop clues and hints but allow the reader to draw their own conclusions.

In a murder mystery, the path to the moment the trigger was pulled is complicated. Perhaps no one knows exactly what led to it, but the author’s task is to include enough clues, hints, and allegations without an info dump.

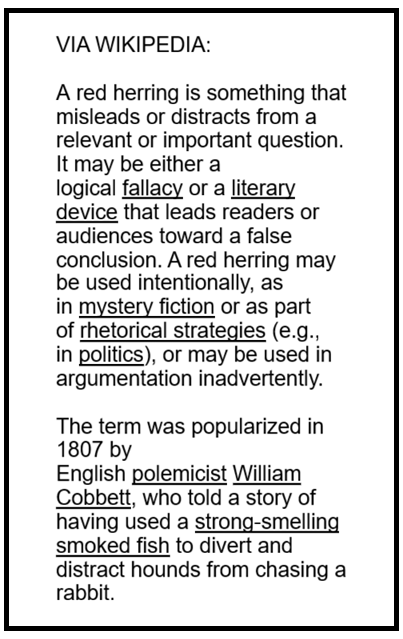

Authors insert clues that imply something to the reader, hints that may be red herrings. One meaning is displayed on the surface, but by using hints and clues, we enclose the secrets within the narrative. The message (inference) in the story is conveyed to the reader, but only if they pick up on the clues.

Authors insert clues that imply something to the reader, hints that may be red herrings. One meaning is displayed on the surface, but by using hints and clues, we enclose the secrets within the narrative. The message (inference) in the story is conveyed to the reader, but only if they pick up on the clues.

The author has to do their job well because we want the reader to feel as if they have earned the information they are gaining. They must be able to deduce what you imply. A reader can only extrapolate knowledge from the information the author offers them.

Serious readers want this layer to mean something on a level that isn’t obvious. They want to experience that feeling of triumph for having caught the meaning. That surge of endorphins keeps them involved and makes them want more of your work.

This middle layer is, in my opinion, the toughest layer for an author to get a grip on.

Below and sort of intertwined with the middle layer is Layer Three, the Interpretive Layer. This layer will be shallower in Romance novels because the point of the book isn’t a deeper meaning. It’s interpersonal relationships on a surface level. However, there will still be some areas of mystery that aren’t spelled out completely because the interpersonal intrigues are the story.

Books for younger readers might also be less deep on this level because they don’t yet have the real-world experience to understand what is implied.

Layer three is comprised of:

- Themes

- Commentary

- Message

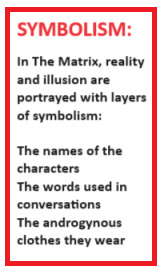

- Symbolism

- Archetypes

This layer is sometimes the easiest for me to discuss because we are dealing with finite concepts. Theme is one of my favorite subjects to write about, as is symbolism. It is an aspect of the narrative I haven’t talked about lately, nor have I really discussed conveying messages. Archetype is another facet I haven’t discussed recently, and yet it is a fundamental underpinning of character building.

This layer is sometimes the easiest for me to discuss because we are dealing with finite concepts. Theme is one of my favorite subjects to write about, as is symbolism. It is an aspect of the narrative I haven’t talked about lately, nor have I really discussed conveying messages. Archetype is another facet I haven’t discussed recently, and yet it is a fundamental underpinning of character building.

For the purposes of this post, commentary is the word that describes the expression of opinions or explanations about an event or situation. Perhaps you are writing a narrative that explores current real-world morals and hypocrisies. If so, this is an important aspect of your work.

I am looking forward to gaining a deeper understanding of the subtler, more abstract aspects of writing as I explore narrative depth. As always, when I come across a book or website with good information, I will share it with you.

In the meantime, a good core textbook is “Story” by Robert McKee. If you haven’t already gotten it, you might want to. It can be found second-hand at Amazon.

Another excellent and more affordable textbook for this is “Damn Fine Story” by Chuck Wendig. Chuck delivers his wisdom in pithy, witty, concise packets. If you fear potty-mouth, don’t buy it. However, if you have the courage to be challenged, this is the book for you.

Most of my novels and short stories begin life as exchanges of dialogue between two characters. Their conversations shed light on what each character’s role in the story might be.

Most of my novels and short stories begin life as exchanges of dialogue between two characters. Their conversations shed light on what each character’s role in the story might be. Action: She comes down for coffee. He holds a notebook, gathers pens, and stands.

Action: She comes down for coffee. He holds a notebook, gathers pens, and stands.