What does “voice” refer to in literature? It is an author’s habit, their fingerprint, a recognizable “sound” in the way they communicate their stories.

When we speak aloud, we habitually use certain words and phrase our thoughts a particular way. The physiology of our throats is unique to us. While we may sound very similar to other members of our family, pitch monitoring software will show that our speaking voice is distinctive to us.

When we speak aloud, we habitually use certain words and phrase our thoughts a particular way. The physiology of our throats is unique to us. While we may sound very similar to other members of our family, pitch monitoring software will show that our speaking voice is distinctive to us.

For some of us, the moment we say “hello,” our friends and family know it’s us on the other end of the telephone, even without caller ID.

The same is true for our writing.

Our voice is comprised of the way we construct paragraphs, the words we choose, and the narrative mode and time/tense we prefer to write in.

Our content is shaped by our deeply held beliefs and attitudes. Those values change and evolve over time. Content includes the themes we instinctively write into our work and the ideals we subconsciously hold dear. Those elements shape a story’s character and plot arcs and represent who we were at the time we wrote it.

Our voice or style is the visual sound of our words as they appear on the page.

Let’s take another look at Gillian Flynn’s novel, Gone Girl.

Flynn’s style of prose is rapid-fire, almost stream-of-consciousness, and yet it is controlled and deliberate. She is creative in how she uses the literary device of narrative mode. Primarily, Gone Girl is written in the first person present tense. But sometimes Flynn breaks the fourth wall by flowing into the second person present tense and speaking directly to us, the reader.

Flynn’s style of prose is rapid-fire, almost stream-of-consciousness, and yet it is controlled and deliberate. She is creative in how she uses the literary device of narrative mode. Primarily, Gone Girl is written in the first person present tense. But sometimes Flynn breaks the fourth wall by flowing into the second person present tense and speaking directly to us, the reader.

This seamless manipulation of narrative tense reveals Flynn’s thought process.

One criticism you might hear about her style is that, at times, her characters all sound alike. Only the chapter title and subjects covered in that section let you know which person is speaking, Nick or Amy. That means we are hearing the author’s own voice in the role of the characters.

When Flynn slips into the second person mode and speaks directly to the reader, she forces us to consider the ideas she is presenting, involving us in the story.

That flowing from mode to mode is a literary device she is good at, and speaking as an editor, it is neither good nor bad. Whether it works depends on an author’s skill.

Your enjoyment of that kind of narrative depends on your personal taste. Flynn’s style of writing is unique, but her exploration of dark, unlikeable characters makes this a difficult novel for some readers.

A writer’s personal ethics and taste and the kernel of “what if” shape how they approach the subject matter and the themes of their work. Their knowledge of craft is demonstrated in the construction of sentences, paragraphs, and scenes. Skill in the craft shapes the overall arc of a story.

courtesy Office 360 graphics

The words we gravitate to and reuse and how we unconsciously punctuate our sentences combine to form our voice, our style.

This personal sound evolves as we develop more skills and knowledge of writing craft.

My own style has changed dramatically since my first novel. When I began writing seriously, I was in the habit of using italicized thoughts and characters talking to themselves to express what was happening inside them. I often employed compound sentences that, when I look back on them now, were too long.

Using italics for thoughts is an accepted practice and is not wrong. When used sparingly, italicized thoughts and internal dialogue have their place. However, thoughts can be used as a means for dumping information, which then becomes a wall of italicized words.

In the last few years, I’ve evolved in my writing habits. I am increasingly drawn to writing shorter sentences, but I vary sentence length to avoid choppiness.

When conveying my character’s internal dialogue, I use the various forms of free indirect speech to show who my characters think they are and how they see their world. So, in that regard, my author voice has changed.

We write for ourselves first. Then, we revise and edit for the enjoyment of other readers.

We do not iron the life out of our work, because that spark of joy that was instilled the moment we laid down those words must still shine through. It takes thought and the ability to recognize and cast aside prose that doesn’t say what we want it to, yet still have it sound like our writing and not someone else’s.

Be consistent with punctuation, whether you are right or wrong. If you “hate the Oxford comma” or some other widely accepted rule of grammar, you must be consistent when you avoid its use.

Inconsistency in a manuscript is not a voice or style.

It’s a mess.

Ernest Hemmingway rarely used commas. However, he was consistent in how he composed his sentences, and his work was original and readable.

“I was learning something from the painting of Cézanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them. I was learning very much from him but I was not articulate enough to explain it to anyone. Besides it was a secret.”

~~Ernest Hemmingway, A Movable Feast

Some authors’ voices really stand out, and their writing skills are up to the task of conveying what they intend their words to say. Their stories find an important place in our hearts.

They are the writers that agents are desperately seeking.

The final aspect of narrative voice or style arises from our deeply held beliefs and attitudes. We may or may not consciously intend to do it, but our convictions emerge in our writing, shaping character and plot arcs.

The final aspect of narrative voice or style arises from our deeply held beliefs and attitudes. We may or may not consciously intend to do it, but our convictions emerge in our writing, shaping character and plot arcs. Whether or not we are aware of it, our societal and religious beliefs emerge in our writings. Subliminal fears of climate change, worry about a world on the edge of economic collapse, and our hopes for a better society come out in our plot arcs and world-building. How they appear may have nothing to do with real life, but they add color to our worlds.

Whether or not we are aware of it, our societal and religious beliefs emerge in our writings. Subliminal fears of climate change, worry about a world on the edge of economic collapse, and our hopes for a better society come out in our plot arcs and world-building. How they appear may have nothing to do with real life, but they add color to our worlds.

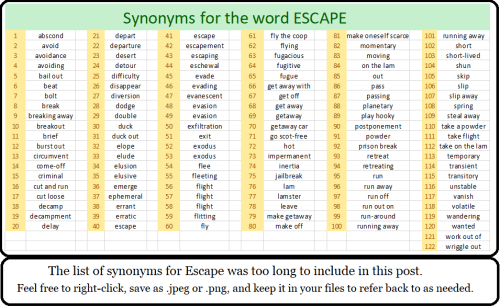

Why do I say such a terrible thing? It’s true. All stories are derived from a few basic plots, and we have only so many words in the English language with which to tell them.

Why do I say such a terrible thing? It’s true. All stories are derived from a few basic plots, and we have only so many words in the English language with which to tell them. Overcoming the monster

Overcoming the monster For that reason, I have the

For that reason, I have the  Noisy

Noisy My Texan editor refers to those convoluted morsels of madness as “

My Texan editor refers to those convoluted morsels of madness as “

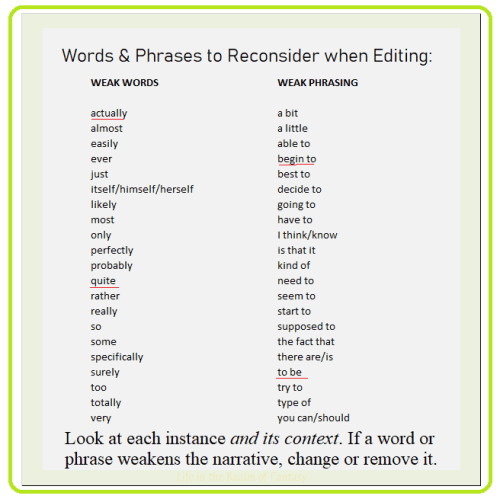

Today’s post focuses on word choice. What do you want to convey with your prose? This is where the choice and placement of words come into play. Active prose is constructed of nouns followed by verbs or verbs followed by nouns.

Today’s post focuses on word choice. What do you want to convey with your prose? This is where the choice and placement of words come into play. Active prose is constructed of nouns followed by verbs or verbs followed by nouns. The second draft revisions are where I do the real writing. It involves finetuning the plot arc, character arcs, and most importantly, adjusting phrasing.

The second draft revisions are where I do the real writing. It involves finetuning the plot arc, character arcs, and most importantly, adjusting phrasing. Some types of narratives should feel highly charged and action-packed. Most of your sentences should be constructed with the verbs forward if you write in genres such as sci-fi, political thrillers, and crime thrillers.

Some types of narratives should feel highly charged and action-packed. Most of your sentences should be constructed with the verbs forward if you write in genres such as sci-fi, political thrillers, and crime thrillers. What clues should you look for when trying to see why someone says you are too wordy?

What clues should you look for when trying to see why someone says you are too wordy?

Some authors are forceful in their style and throw you into the action. They have an in-your-face, hard-hitting style that comes on strong and doesn’t let up until the end.

Some authors are forceful in their style and throw you into the action. They have an in-your-face, hard-hitting style that comes on strong and doesn’t let up until the end. “I’m going to send you over. The chances are you’ll get off with life. That means you’ll be out again in twenty years. You’re an angel. I’ll wait for you.” He cleared his throat. “If they hang you I’ll always remember you.” [1]

“I’m going to send you over. The chances are you’ll get off with life. That means you’ll be out again in twenty years. You’re an angel. I’ll wait for you.” He cleared his throat. “If they hang you I’ll always remember you.” [1] But I prefer to keep my research in hardcopy form, rather than digital.

But I prefer to keep my research in hardcopy form, rather than digital.  As we become confident in our writing, we learn more about grammar and punctuation in our native languages. We learn to write so others can understand us.

As we become confident in our writing, we learn more about grammar and punctuation in our native languages. We learn to write so others can understand us. However, quantifiers have a bad reputation because they can quickly become habitual, such as the word very.

However, quantifiers have a bad reputation because they can quickly become habitual, such as the word very. Our narrative voice comes across in our choice of hard or soft words and where we habitually position verbs in a sentence. Where we automatically place the words in the sentence is a recognizable fingerprint.

Our narrative voice comes across in our choice of hard or soft words and where we habitually position verbs in a sentence. Where we automatically place the words in the sentence is a recognizable fingerprint.