I’ve been struggling to find the place where the narrative of my new novel actually begins. Is it the day of his divorce? Is it the day of his brother’s death? Or is it the day he is released from the care of the healers after his breakdown?

And what of my female protagonist? Where does her story begin?

And what of my female protagonist? Where does her story begin?

And the other pair—the ones that really need their own book but aren’t going to get it. What about them?

At this point, all I have is a mountain of backstory. It’s important because it tells me who my people are the day the novel begins.

It doesn’t need to be the opening chapter.

Every story begins with an opening act. The characters are introduced, and the scene is set. These paragraphs establish the tone of what is to follow, and if I have gotten my phrasing and pacing right, they will hook the reader.

This is where pacing comes into it. The intended impact of the book can and should be established in the first pages—but it takes work. I am writing a first draft right now, so most of what I write is a code telling me what I need to know when I get to the revision process.

I have introduced the setting. Where are the characters? Well, in this case, it’s easy. They are in the World of Neveyah, and fortunately for me, the world, the society, and the magic systems are already built. Some things are canon, which forces me to be creative and work within those limits.

Finally, I must introduce the conflict. What does the protagonist want? What hinders them?

My female protagonist must learn to live with her limits and trust her team. She must learn to delegate.

While she is doing that, my male protagonist must move beyond what he has lost and learn to appreciate what he still has.

My other female lead must be the friend the protagonist needs and make a choice between her career as a soldier or choosing to leave and raise a family.

Conversely, the other male lead must emerge from his father’s domination and choose to make his career as an artisan.

Not only that, but I must use my words in such a way that my readers don’t want to put the book down.

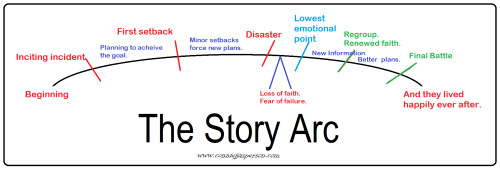

Novels are built the same way as a Gothic cathedral. Small arcs support other arcs in layers, creating an intricate structure that rises high and withstands all that nature can throw at it for the centuries to come.

Like our cathedral, the strength of a novel’s story arc depends on the foundation you lay in the book’s first quarter.

I must introduce a story-worthy problem in those pages, a test propelling the protagonist to the middle of the book. The opening paragraphs are vital. They are the hook, the introduction to my voice, and must offer a reason for the reader to continue past the first page.

I must introduce a story-worthy problem in those pages, a test propelling the protagonist to the middle of the book. The opening paragraphs are vital. They are the hook, the introduction to my voice, and must offer a reason for the reader to continue past the first page.

So, I must find where that story really begins, and trust me, it isn’t with a mental breakdown. The story begins with each character arriving at their new duty stations, each with a history that makes them who they are that day. Their pasts are known to others and do come out, but only when the other characters and the reader needs it.

I find pacing is the most challenging part of writing a first draft. Eighty percent of my writing will not make it into the final manuscript.

But it will be available in a file labeled ‘backstory’ for me to access when needed. I note names and relationships in my stylesheet and outline as I go.

One character is dark and brooding. I won’t explain why at the outset, as his backstory must emerge gradually, each morsel emerging when my female character must know. My side characters have an easier path, but their task is to provide information when required and to assist in the surface quest—catching a murderer.

With the back history in a separate file, I must open the novel with my characters in place. A question must be raised, or I must introduce the inciting incident. This sets the four on the trail of the answer, throwing them into the action.

It’s too easy to frontload the opening pages with a wall of backstory. We always think, “Before you learn this, you must know that.”

All of that is true, but the history belongs in a separate file. I learned this the hard way—long lead-ins don’t hook the reader.

If my characters don’t need to hear the history of the Caverns of Despair, it’s likely that the readers also don’t care. The name is a pretty descriptive indicator of what lies ahead, so the twelve paragraphs detailing how the caves got their name are probably unnecessary.

My favorite books open with a minor conflict, evolving to a series of more significant problems, working up to the first pinch point, where the characters are set on the path to their destiny.

My favorite books open with a minor conflict, evolving to a series of more significant problems, working up to the first pinch point, where the characters are set on the path to their destiny.

I will open with a strong scene, an arc of action that

- illuminates the characters’ motives,

- allows the reader to learn things as the protagonist does, and

- offers clues regarding things the characters do not know that will affect the plot.

- The end of one scene is the launching pad for the next scene, propelling the story arc.

The clues I offer at the beginning are foreshadowing. Through the book’s first half, foreshadowing is important, as it piques the reader’s interest and makes them want to know how the book will end.

In the opening paragraphs, I will focus on the protagonists and hint at their problems. Subplots, if there are any, will be introduced after the inciting incident has taken place. They must relate to that incident in some way.

If you introduce side quests too soon, they are distracting. They make for a haphazard story arc if they don’t relate to the central quest. I think side quests work best if they are presented once the book’s tone and the central crisis have been established. Good subplots are excellent ways of introducing the emotional part of the story.

Even if I were to open the story by dropping my characters into the middle of an event, I’d need a pivotal event at the 1/4 mark that completely rocks their world. The event that changes everything is the core of the story.

Following the inciting incident is the second act: more action occurs, leading to more trouble and rising to a severe crisis.

I know how long I plan the book to be. I will take that word count and divide it by 4. I place the first significant event in the first quarter, presenting it after I introduce the characters. The following two quarters form the second act, the middle. If I have plotted well, the middle of the story arc should fall into place like dominoes.

We’ll talk about that in my next post.