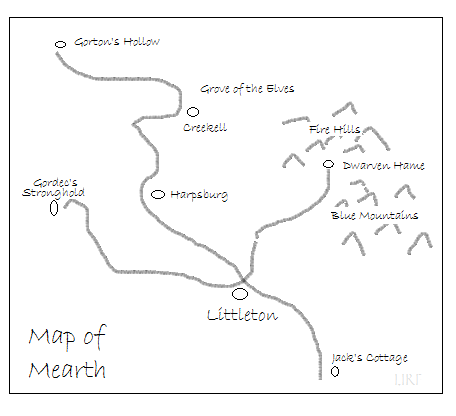

Time can get a little mushy when I am winging it through a manuscript. I discovered early on that keeping a calendar and a map gives me a realistic view of how long it takes my characters to travel from point A to point B.

Also, the two combine to help in deciding how long it will take to complete a task.

Also, the two combine to help in deciding how long it will take to complete a task.

It helps to know what season your events occur in, as foliage changes with the seasons, and weather is a part of worldbuilding. But there are other reasons for keeping a calendar as well as sketching a map.

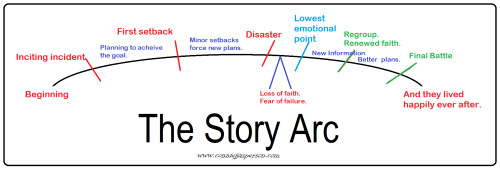

A calendar helps you with pacing and consistency. In conjunction with a map, a calendar keeps the events moving along the story arc. It ensures you allow enough time to reasonably accomplish large tasks, enabling a reader to suspend their disbelief.

They ensure you don’t inadvertently jump from season to season when describing the scenery surrounding the characters.

The calendar keeps the timeline believable. Here is where I confess my great regret: in 2008, a lunar calendar seemed like a good thing while creating my first world.

- Thirteen months, twenty-eight days each,

- One extra day at the end of the year, which ends on the Winter solstice.

- Winter solstice is called Holy Day. Every four years, they have two Holy Days and a big party.

That arrangement of thirteen months is easy to work with because it is on paper. However, the names I assigned to the dates and months are problematic.

While I had finished the RPG game’s plot and the synopsis, I didn’t have some details of the universe and the world figured out. So, in a burst of creative predictability, I went astrological in naming the months. I thought it would give the player a feeling of familiarity.

While I had finished the RPG game’s plot and the synopsis, I didn’t have some details of the universe and the world figured out. So, in a burst of creative predictability, I went astrological in naming the months. I thought it would give the player a feeling of familiarity.

We were only beginning to design the game when it was scrapped. Fortunately, I retained the rights to my work. Unfortunately, the calendar I had invented for the RPG was incorporated into the world of Neveyah, and now (while I wish it wasn’t) it is canon.

In a bout of desperate unoriginality, I went with the names we currently use when I named the days, except—I twisted them a bit and gave them the actual Norse god’s name. The gods and goddesses of Neveyah are not Norse.

I could have changed all of that when the game was abandoned, but it didn’t occur to me. That lapse is an example of how what seems like a good idea at the time might not be workable in practice.

One thing I did right was sticking to a 24-hour day and a standard 12-hour clock. Experience is a cruel teacher. I can’t stress enough how important it is to keep things simple when we are world-building. Simplicity minimizes chaos when the plot gets complicated.

Time has a tendency to be elastic when we are writing the first draft of a story where many events must occur. Sometimes, many things are accomplished in too short a period for a reader to suspend their disbelief.

Time has a tendency to be elastic when we are writing the first draft of a story where many events must occur. Sometimes, many things are accomplished in too short a period for a reader to suspend their disbelief.

Calendars are maps of time. They turn the abstract concept of time into an image we can understand.

Even though I regret how I named the days in Mountains of the Moon, I have a calendar, so my characters progress through their space-time continuum at a rate I can comprehend. I can adjust events in the first and second drafts, moving them forward or back in time by looking at and updating their calendar. The sequence of events forming the plot arc remains believable.

I heartily suggest you stick to a simple calendar. That is the advice I would give any new writer—stick to something close to the calendar we’re familiar with, and don’t get too fancy.

Speaking of fancy, what about distance? Stories often involve traveling, and in fantasy tales, one could be walking or riding a horse. The distance a person can walk in one hour depends on the walking speed and the terrain. People can walk between 2.0 miles (3.22 K) and 5.0 miles (8.47 K) in 1 hour (60 minutes) depending on walking speed. A healthy person can probably walk 5 to 7 miles (8.04 to 11.256 K) in two hours of walking at a steady pace.

What if your fantasy world uses leagues as a measure of distance? A league is 3.452 miles or 5.556 kilometers. Generally speaking, a horse can walk 32 miles or 51.5 K in a day.

What if your fantasy world uses leagues as a measure of distance? A league is 3.452 miles or 5.556 kilometers. Generally speaking, a horse can walk 32 miles or 51.5 K in a day.

Thus, a day of walking or riding a horse on a level road can take one quite a distance.

But roads are NOT always level, and they don’t always cross flat ground.

As I said above, the distance a person can walk in one hour depends on the walking speed and the terrain. But let’s say you settle down and walk at a steady speed. If you go at the typical walking pace of 15 to 20 minutes per mile, it could take you 2–3 hours to get to your destination if it is ten miles (16 K) away on a good road.

If you are writing sci-fi or fantasy, calendars, and rudimentary maps work together to keep the plot moving and believable. Will your characters encounter forests? Mountains? Rivers?

Maybe they live in a city.

Each of these areas will impact how long it takes to go from one place to another. This is where a calendar comes into play.

Many readers have a route they walk or run daily to maintain their health. These readers will know how long it takes to walk ten blocks. They will also know how far a healthy person can walk in one hour on a good road.

Many readers have a route they walk or run daily to maintain their health. These readers will know how long it takes to walk ten blocks. They will also know how far a healthy person can walk in one hour on a good road.

This is where the map comes into play. You can’t travel in a straight line over mountains or forests. Sometimes, you must travel parallel to a river for a long way until you come to a place shallow enough to cross.

The part of the world where I live has large tracts of forests, many wide rivers, and is mountainous, with numerous volcanos. Our roads are often winding and sometimes travel in switchbacks up and over many of these obstacles. It takes time to go places even though the original road-builders plotted the roads through the most accessible paths.

The part of the world where I live has large tracts of forests, many wide rivers, and is mountainous, with numerous volcanos. Our roads are often winding and sometimes travel in switchbacks up and over many of these obstacles. It takes time to go places even though the original road-builders plotted the roads through the most accessible paths.

And we’ll just toss this out there – while you can drop a tall tree across a narrow creek, building bridges over rivers requires a certain amount of engineering. Cultures from the Neolithic to modern times have had the skills needed to make bridges.

We are creative, and archaeology shows us that our ancestors were capable of far more than we have traditionally believed. Archeology and history both tell us that humans, as a species, are tribal by nature. We band together for protection, shelter, better access to resources, and companionship, and these gathering places become towns.

Humans have always created communities where resources are plentiful, but climate changes over time.

Your maps should take into consideration all the terrain your characters must deal with.

Travel and events take time. A calendar, either fantasy or the standard Gregorian calendar we use today, and a simple hand-drawn map will help you maintain the logic of your plot.

Travel and events take time. A calendar, either fantasy or the standard Gregorian calendar we use today, and a simple hand-drawn map will help you maintain the logic of your plot.

And what of my female protagonist? Where does her story begin?

And what of my female protagonist? Where does her story begin? I must introduce a story-worthy problem in those pages, a test propelling the protagonist to the middle of the book. The opening paragraphs are vital. They are the hook, the introduction to my voice, and must offer a reason for the reader to continue past the first page.

I must introduce a story-worthy problem in those pages, a test propelling the protagonist to the middle of the book. The opening paragraphs are vital. They are the hook, the introduction to my voice, and must offer a reason for the reader to continue past the first page. My favorite books open with a minor conflict, evolving to a series of more significant problems, working up to the first pinch point, where the characters are set on the path to their destiny.

My favorite books open with a minor conflict, evolving to a series of more significant problems, working up to the first pinch point, where the characters are set on the path to their destiny.

Volume control is a crucial part of the overall pacing of your story. “Loud” deafens us and loses its power when it’s the only sound. However, like the opening movement of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, the entire range of volume can be effectively used to create a masterpiece.

Volume control is a crucial part of the overall pacing of your story. “Loud” deafens us and loses its power when it’s the only sound. However, like the opening movement of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, the entire range of volume can be effectively used to create a masterpiece. Dark emotions, such as depression, can be shown through a character’s reactions to things that once pleased them. Perhaps they no longer find beauty in the things they once enjoyed.

Dark emotions, such as depression, can be shown through a character’s reactions to things that once pleased them. Perhaps they no longer find beauty in the things they once enjoyed. Visceral reactions are involuntary—we can’t stop our face from flushing or our heart from pounding. We can pretend it didn’t happen or hide it, but we can’t stop it. An internal physical gut reaction is difficult to convey without offering the reader some information, a framework to hang the image on.

Visceral reactions are involuntary—we can’t stop our face from flushing or our heart from pounding. We can pretend it didn’t happen or hide it, but we can’t stop it. An internal physical gut reaction is difficult to convey without offering the reader some information, a framework to hang the image on. Conflict keeps the protagonist from achieving their goals. Significant conflicts and emotions are easy to write about. But in real life, our smaller, more internal conflicts frequently create more significant roadblocks to success than any antagonist might present.

Conflict keeps the protagonist from achieving their goals. Significant conflicts and emotions are easy to write about. But in real life, our smaller, more internal conflicts frequently create more significant roadblocks to success than any antagonist might present.

![I, Sailko [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/benozzo_gozzoli_corteo_dei_magi_1_inizio_1459_51.jpg?w=198&h=300)

![Sir Galahad, George Frederic Watts [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/220px-sir_galahad_watts.jpg?w=147&h=300)