Last week’s post, Idea to story, part 2: thinking out loud #writing, discussed how plots evolve as I design the main characters for a story. Our two main characters are Val (Valentine), a lady knight, and the enemy, Kai Voss, court sorcerer. Both are regents for the sickly, underage king.

The plot as it stood last week: Kai Voss has tired of being merely a co-regent. Twelve-year-old Edward has been steadily declining in health since the deaths of his parents. His bodyguards, led by Val, believe the sorcerer is the cause. This idea of the plot will evolve as we get to know our bad boy better.

The plot as it stood last week: Kai Voss has tired of being merely a co-regent. Twelve-year-old Edward has been steadily declining in health since the deaths of his parents. His bodyguards, led by Val, believe the sorcerer is the cause. This idea of the plot will evolve as we get to know our bad boy better.

At this point in our ruminations, we think we’re writing a novel, but we won’t know the final length until we’re much further along in this process.

Today, we’re going to design the plot for Val and Kai Voss’s story.

You’ll note that I say it is also the antagonist’s story. I say this because his story is why Val has a quest. So, today, we’re going to do a little more thinking out loud. Let’s take the notebook and the pencil out to the balcony and let Val’s story ferment a bit.

We had a good look at Val last week, so now we’ll meet and get to know Kai Voss. I know it seems backwards, but this is how I work. Good villains are the fertile soil from which a great plot can grow. Once we know who he is and how he thinks, we can help him make plans to stop Val and her soldiers.

We had a good look at Val last week, so now we’ll meet and get to know Kai Voss. I know it seems backwards, but this is how I work. Good villains are the fertile soil from which a great plot can grow. Once we know who he is and how he thinks, we can help him make plans to stop Val and her soldiers.

First, I assign nouns that tell us how he sees himself at the story’s outset. I also look at sub-nouns and synonyms, which means I must put my thesaurus to work. The sorcerer’s nouns are bravado (boldness, brashness), daring, and courtliness.

Our lad is definitely a charmer.

Kai also has verbs that show us his gut reactions: defend, fight, desire, preserve.

You will note the word defend is the lead verb in Kai’s description. What must he defend, and how does Valentine threaten him? At the age of sixteen, Val ran away from an arranged marriage, abandoning a woman’s traditional role. As such, Kai believes she is a bad influence on all the women she comes into contact with.

As we flesh out his character, we realize that he fears what Val’s very existence represents—a woman who escaped being forced into marriage and who successfully makes her own way in the world. Now thirty-five, she is captain of the royal guard and is a co-regent of the young, sickly king. Most importantly, her advice has a substantial impact on the young king, who sees her as a mother figure.

Kai is also thirty-five and while he has never found the right time for marriage, he feels compelled to defend the traditional roles of male supremacy. He must preserve what he believes is best for the young king and, through him, the country.

As you can see, the plot idea has already changed, veering away from a simple good vs. evil hero’s journey. I am finally realizing what kind of story is really trying to emerge.

A character’s preconceptions color their experience of events. We see the story through their eyes, which colors how we see the incidents.

- Val is a commoner who came up through the ranks of the royal guard and found favor with the young king’s parents. She has a great deal of disdain for the feckless nobility that inhabits the court and Kai can sense it. Her goal is to keep young King Edward alive and raise him to have compassion even for the least of his subjects.

- Kai is a privileged noble with no idea of how the ordinary people really live. He also has one more noun, one that overrides all the others and informs his subsequent actions: fear. Kai’s goal is the same as Val’s, which is to keep young Edward alive, and failing that, to make sure the traditional ways continue.

However, Kai sees a dark future and must teach Edward the values of his ancestors, to ensure that the nobility retains their rights of absolute power.

He believes that the peasantry must be guided by their betters and will be cared for by the nobility. After all, his family treats their serfs well, so he is under the impression that the other lords also act fairly. Fear of what the future holds for the country means he must also position himself to step into the role of king if Edward dies of his wasting illness.

Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will always gloss over their own failings. The story moves ahead each time they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

What are their voids? What words describe the primary weaknesses of your characters, the thing that could be their ultimate ruin?

Val – Arrogance, pigheadedness, and fear of being tied to a brute.

Kai Voss – Arrogance, obsession, and a misplaced sense of honor.

Now that we know our two characters share some of the same flaws, we can set them both up for some hard lessons in reality. What those lessons are will emerge as we progress.

But now I know that, in the end, they will find common ground, as the true enemy has been hiding in plain sight all along, pulling their strings.

In the next installment of this series, we’ll look at plotting the side characters. We’ll discuss the ways they can be used, not only to deliver needed information and provide moments of humor, but in other, more nefarious ways as well.

In the next installment of this series, we’ll look at plotting the side characters. We’ll discuss the ways they can be used, not only to deliver needed information and provide moments of humor, but in other, more nefarious ways as well.

I know we haven’t delved into designing how Kai’s sorcerous skills work or explored Val’s ability in the martial arts. Trust me, we will get there before we wind up this series.

I quickly regretted that decision.

I quickly regretted that decision. Arthur and his court originated as ordinary 5th or 6th-century warlords. But the tales featuring them were written centuries later. Their 11th-century chroniclers presented them in contemporary armor as worn by

Arthur and his court originated as ordinary 5th or 6th-century warlords. But the tales featuring them were written centuries later. Their 11th-century chroniclers presented them in contemporary armor as worn by

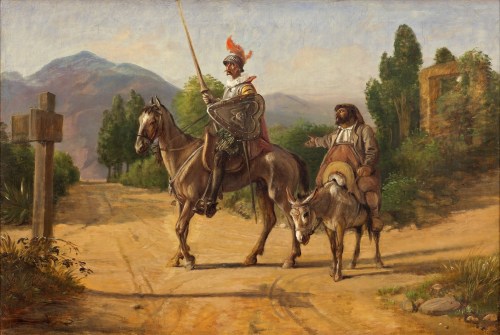

I am an abject fangirl for Don Quixote, so different versions of both Galahad and Quixote appear regularly in my work.

I am an abject fangirl for Don Quixote, so different versions of both Galahad and Quixote appear regularly in my work.

And sometimes a theme refuses to let go of me. I took Arthurian myth and the chivalric code and turned them inside out with the characters of Lancelyn and Galahad in

And sometimes a theme refuses to let go of me. I took Arthurian myth and the chivalric code and turned them inside out with the characters of Lancelyn and Galahad in