I love words. I love the way they rhyme, the way they sound, and the way they feel when they roll off the tongue of a gifted narrator. I love words that sound alike but mean different things, words that describe colors, smells, and sounds.

I love words.

The English language is full of words that mean the same as other words. Even common names are like that. For instance, “Jones” is a surname of Welsh origin that dates back to the Middle Ages. It means “John’s son.” So, Jones is Welsh for Johnson, and the two usages evolved on the same island.

The English language is full of words that mean the same as other words. Even common names are like that. For instance, “Jones” is a surname of Welsh origin that dates back to the Middle Ages. It means “John’s son.” So, Jones is Welsh for Johnson, and the two usages evolved on the same island.

Who knew? Jones seems so dissimilar to Johnson that I (an American) would never have guessed.

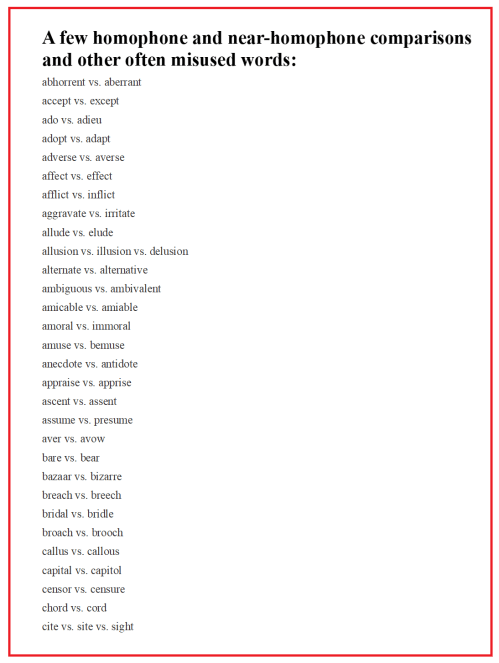

In a strange twist of irony, English is also full of words that sound nearly alike and look very similar but mean very different things. Even though many of these words are often used interchangeably in casual conversation, they are NOT alike or similar in meaning.

I always notice when an author confuses near-homophones. That is the technical term for words that sound closely alike, are spelled differently, and have different meanings. When we read widely, we’re more likely to notice the difference between words like accept and except when they are written.

The different meanings of seldom-used sound-alike words can become blurred among people who have little time to read. They don’t see how a word is written, so they speak it the way they hear it. This is how wrong usage becomes part of everyday English.

The different meanings of seldom-used sound-alike words can become blurred among people who have little time to read. They don’t see how a word is written, so they speak it the way they hear it. This is how wrong usage becomes part of everyday English.

For this reason, new and beginning writers often don’t realize the ways in which they habitually misuse common words until they begin to see the differences in how they are written.

Let’s look at two of the most commonly confused words: accept and except. People, even those with some higher education, frequently mix these two words up in their casual conversation.

Accept (definition) to take or receive (something offered); receive with approval or favor.

- I accept this award.

- We should accept this proposal.

Except (definition) not including, other than, leave out, exclude.

- We’re old, present company excepted.

- Everyone is welcome, with the exclusion of drunks and other miscreants.

Used together in one sentence, they look like this:

We accept that our employees work every day except Sunday.

The following quote is one I have used before, but it’s a good one, so I’ll just repeat myself here.

Farther vs. Further: (Grammar Tips from a Thirty-Eight-Year-Old with an English Degree | The New Yorker by Reuven Perlman, posted February 25, 2021:

Farther describes literal distance; further describes abstract distance. Let’s look at some examples:

-

I’ve tried the whole “new city” thing, each time moving farther away from my hometown, but I can’t move away from . . . myself (if that makes sense?).

-

How is it possible that I’m further from accomplishing my goals now than I was five years ago? Maybe it’s time to change goals? [1]

Consider these three very different words:

- Ensure

- Insure

- Assure

Ensure: When we use these sound-alike words, we want to ensure (make certain something happens) that we are using them correctly.

Insure: We insure our home and auto. In other words, we arrange for compensation in the event of damage or loss of property or the injury to (or the death of) someone. We arrange for compensation should the family breadwinner die (life insurance). Also, we arrange to pay in advance for medical care we may need in the future (health insurance).

Insure: We insure our home and auto. In other words, we arrange for compensation in the event of damage or loss of property or the injury to (or the death of) someone. We arrange for compensation should the family breadwinner die (life insurance). Also, we arrange to pay in advance for medical care we may need in the future (health insurance).

Assure: We assure our listeners that everything is correct. In other words, we explain things in a way that dispels any doubts our listeners may have. If we have to, we reassure them by explaining it twice.

It never hurts to have a wide vocabulary, but we must know the meaning and correct uses of words. For the moment, let’s not worry about grandiose (magnificent, complex, ostentatious, pretentious) words that only inflate our prose. We who write must learn how to use all our words accurately and in a context that says what we mean.

The words listed in the following image are often used interchangeably in common speech, and while it may sound normal when your friend says persecute when she means prosecute, incorrect usage conveys the wrong meaning.

I think it helps if a writer is also a poet. When writing a narrative, we have room for a lot more words, which can lead to inflated prose. But when writing poetry, we must do more with less, so the words we choose must have a visual, sensory impact.

Isn’t that what we hope to achieve with all our work?

I have one manuscript in the final revision stage and am working on shrinking the prose while conveying the story. The real struggle for me is achieving uninflated yet visual prose.

I have a lot of words to choose from, and the Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms to help me out. It’s full to overflowing with lovely, visual, sensory words, and like an addict, I have the urge to use them all.

I have a lot of words to choose from, and the Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms to help me out. It’s full to overflowing with lovely, visual, sensory words, and like an addict, I have the urge to use them all.

But I won’t. Today, I will write lean, descriptive prose. If I don’t, my editor will ensure that I pare the fluff down.

Discipline feels good.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Farther vs. Further: (Grammar Tips from a Thirty-Eight-Year-Old with an English Degree | The New Yorker by Reuven Perlman, posted February 25, 2021 (accessed 18 May 2024).

However, obscure and pretentious prose (such as I enjoyed laying down in the preceding sentence) annoys the majority of readers. I want my work to please a reader, so I don’t indulge in ostentatious phrasing except in poetry.

However, obscure and pretentious prose (such as I enjoyed laying down in the preceding sentence) annoys the majority of readers. I want my work to please a reader, so I don’t indulge in ostentatious phrasing except in poetry. Mama and Dad both invented words and twisted others: a screwdriver was a skeejabber. Any object can be a doo-dad, but they were often doodle-be-dads in our house. When one or the other parent was mystified, they were bumfuzzled.

Mama and Dad both invented words and twisted others: a screwdriver was a skeejabber. Any object can be a doo-dad, but they were often doodle-be-dads in our house. When one or the other parent was mystified, they were bumfuzzled. The trick is to understand that, while the first draft has many passages that shine, more of what we have written is only promising. The first draft contains the seeds of what we believe we have written. Like a sculptor, we must work to shave away the detritus and reveal the truth of the narrative.

The trick is to understand that, while the first draft has many passages that shine, more of what we have written is only promising. The first draft contains the seeds of what we believe we have written. Like a sculptor, we must work to shave away the detritus and reveal the truth of the narrative. The best resource you can have in your personal library is a dictionary of synonyms and antonyms. Your word processing program may offer you some synonyms when you right click on a word. However, to develop a wide vocabulary of commonly understood words, you should try to find a book like the

The best resource you can have in your personal library is a dictionary of synonyms and antonyms. Your word processing program may offer you some synonyms when you right click on a word. However, to develop a wide vocabulary of commonly understood words, you should try to find a book like the