In the previous post, we talked about scene framing. Scenes are word pictures, portraits of a moment in a character’s life framed by the backdrop of the world around them. Everything depicted in that scene has meaning.

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

Transitions bookend each scene, and the way we use those transitions determines the importance of the passage. The bookends determine the narrative’s pacing.

Transition scenes get us smoothly from one event or conversation to the next. They push the plot forward. Action, transition, action, transition—this is pacing.

The pacing of a story is created by the rise and fall of action.

- Action: Our characters do

- Visuals: We see the world through their eyes; they show us something.

- Conversations: They tell us something, and the cycle begins again.

Do.

Show.

Tell.

I picked up my kit and looked around. No wife to kiss goodbye, no real home to leave behind, nothing of value to pack. Only the need to bid Aeoven and my failures goodbye. The quiet snick of the door closing behind me sounded like deliverance.

The character in the above transition scene completes an action in one scene and moves on to the next event. It reveals his mood and some of his history in 46 words and propels him into the next scene.

He does something: I picked up my kit and looked around.

He shows us something: No wife to kiss goodbye, no real home to leave behind, nothing of value to pack. Only the need to bid Aeoven and my failures goodbye.

He tells us something: The quiet snick of the door closing behind me sounded like deliverance.

The door has closed, there is no going back, and he is now in the next action sequence. We find out who and what is waiting for him on the other side of that door.

All fiction has one thing in common regardless of the genre: characters we can empathize with are thrown into chaos with a plot.

Remember the blank wall from above and the random pictures placed on it?

Our narrative begins as a blank wall strewn with pictures. We take those pictures and add transition pictures to create a coherent story out of the visual chaos.

This is where project management comes into play—we assign an order to how the scenes progress.

- Processing the action.

- Action again.

- Processing/regrouping.

Our job is to make the transitions subliminal. We are constantly told, “Don’t waste words on empty scenes.” To be honest, I know a lot of words, and wasting them is my best skill.

Our bookend scenes are not empty words. They should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They lay the groundwork for what comes next.

Our bookend scenes are not empty words. They should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They lay the groundwork for what comes next.

What makes a memorable story? In my opinion, the emotions it evoked are why I loved a particular novel. The author allowed me to process the events and gave me a moment of rest and reflection between the action.

I was with the characters when they took a moment to process what had just occurred. That moment transitions us to the next scene.

These information scenes are vital to the reader’s understanding of why these events occur. They show us what must be done to resolve the final problem.

The transition is also where you ratchet up the emotional tension. As shown in the example above, introspection offers an opportunity for clues about the characters to emerge. A “thinking scene” opens a window for the reader to see who they are and how they react. It illuminates their fears and strengths, and makes them seem real and self-aware.

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals.

With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. (Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.)

Fade-to-black is a time-honored way of moving from one event to the next. However, I dislike using fade-to-black scene breaks as transitions within a chapter. Why not just start a new chapter once the scene has faded to black?

One of my favorite authors sometimes has chapters of only five or six hundred words, keeping each character thread separate and flowing well. A hard scene break with a new chapter is my preferred way to end a nice, satisfying fade-to-black.

One of my favorite authors sometimes has chapters of only five or six hundred words, keeping each character thread separate and flowing well. A hard scene break with a new chapter is my preferred way to end a nice, satisfying fade-to-black.

Chapter breaks are transitions. I have found that as I write, chapter breaks fall naturally at certain places.

Every author develops habits that either speed up or slow down the workflow. I use project management skills to keep every aspect of life moving along smoothly, and that includes writing.

In my world, the first draft of any story or novel is really an expanded outline. It is a series of scenes that have characters talking or doing things. But those scenes are disconnected. The story is choppy, nothing but a series of events. All I was concerned about was getting the story written from the opening scene to the last page and the words “the end.”

The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next.

The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next.

Yes, that first draft manuscript was finished in the regard that it had a beginning, middle, and ending.

But I was too involved and couldn’t see that while each scene was a picture of a moment in time, it was only a skeleton, a pile of bones.

By setting it aside for a while, I’m able to see it still needs muscles and heart and flesh. Transitions layer those elements on, creating a living, breathing story.

Credits and attributions:

IMAGE: Title: The Sciences and Arts

Artist: Hieronymous Francken II (1578–1623) or Adriaen van Stalbemt (1580–1662)

Genre: interior view

Date: between 1607 and 1650

Medium: oil on panel

Dimensions: height: 117 cm (46 in); width: 89.9 cm (35.3 in)

Collection: Museo del Prado

Notes: This work’s attribution has not been determined with certainty with some historian preferring Francken over van Stalbemt. See Sotheby’s note. Sold 9 July 2014, lot 57, in London, for 422,500 GBP

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Stalbent-ciencias y artes-prado.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Stalbent-ciencias_y_artes-prado.jpg&oldid=699790256 (accessed March 12, 2024).

In writing, this happens when the narrative keeps expanding, and expanding, and expanding … and what was canon in chapter 4 is contradicted in chapter 44. The story grows as we write it.

In writing, this happens when the narrative keeps expanding, and expanding, and expanding … and what was canon in chapter 4 is contradicted in chapter 44. The story grows as we write it.

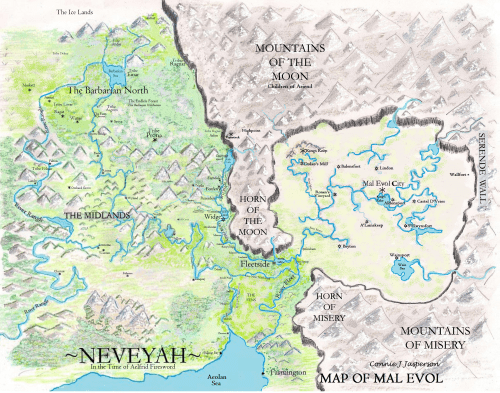

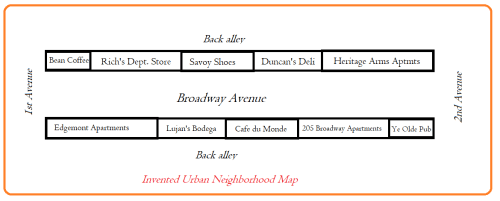

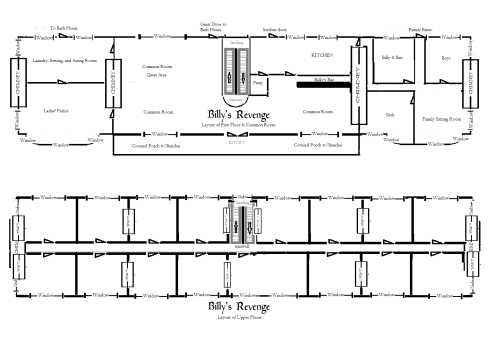

If you are writing a tale set in a fantasy or sci-fi setting, you are creating that world.

If you are writing a tale set in a fantasy or sci-fi setting, you are creating that world.

Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. Use a pencil to easily update your map if something changes during revisions. You want to know:

Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. Use a pencil to easily update your map if something changes during revisions. You want to know: The plan or design is submitted to the client, who likes it. A mockup of the first iteration is submitted to the client, who still likes it, but … their needs have changed a little, and a new adjustment must be incorporated.

The plan or design is submitted to the client, who likes it. A mockup of the first iteration is submitted to the client, who still likes it, but … their needs have changed a little, and a new adjustment must be incorporated. Books are one area where project creep is not only appreciated but encouraged. Stories are particularly prone to this continual expansion of the original ideas. Short stories grow into novellas and then into novels, becoming a series of books.

Books are one area where project creep is not only appreciated but encouraged. Stories are particularly prone to this continual expansion of the original ideas. Short stories grow into novellas and then into novels, becoming a series of books. The first aspect of this is to Identify your Project Goals – create a rudimentary outline with names, who they are in relation to the protagonist, and decide who is telling the story. Remember, your story is your invention. Some inventions are in development for years before they get to market. Others are complete and ready to market in a relatively short time. Regardless of your production timeline, this is where project management skills really come into play.

The first aspect of this is to Identify your Project Goals – create a rudimentary outline with names, who they are in relation to the protagonist, and decide who is telling the story. Remember, your story is your invention. Some inventions are in development for years before they get to market. Others are complete and ready to market in a relatively short time. Regardless of your production timeline, this is where project management skills really come into play. Your map doesn’t have to be fancy – all you need are some lines and scribbles telling you all the essential things, like which direction is north and what certain towns are named. Use a pencil, to easily update your map if something changes during revisions.

Your map doesn’t have to be fancy – all you need are some lines and scribbles telling you all the essential things, like which direction is north and what certain towns are named. Use a pencil, to easily update your map if something changes during revisions. Time can get a little mushy when we are winging it through a manuscript. A calendar gives us a realistic view of how long it takes to travel from point A to point B, or how much time it will take to complete a task.

Time can get a little mushy when we are winging it through a manuscript. A calendar gives us a realistic view of how long it takes to travel from point A to point B, or how much time it will take to complete a task.