Proofreading is not editing, nor is beta reading. These are three different stages of preparing a manuscript for publication.

Beta Reading is the first look at a manuscript by someone other than the author. The first reading by an unbiased eye is meant to give the author a view of their story’s overall strengths and weaknesses so that the revision process will go smoothly. This phase should be done before you submit the manuscript to an editor. It’s best when the reader is a person who reads for pleasure and can gently express what they think about a story or novel. Also, look for a person who enjoys the genre of that particular story. If you are asked to be a beta reader, you should ask several questions of this first draft.

Beta Reading is the first look at a manuscript by someone other than the author. The first reading by an unbiased eye is meant to give the author a view of their story’s overall strengths and weaknesses so that the revision process will go smoothly. This phase should be done before you submit the manuscript to an editor. It’s best when the reader is a person who reads for pleasure and can gently express what they think about a story or novel. Also, look for a person who enjoys the genre of that particular story. If you are asked to be a beta reader, you should ask several questions of this first draft.

Setting: Does the setting feel real?

Characters: Is the point of view character (protagonist) clear? Did you understand what they were feeling? Were they likable? Did you identify with and care about them? Were there various character types, or did they all seem the same? Were their emotions and motivations clear and relatable?

Dialogue: Did the dialogue and internal narratives advance the plot?

Pacing: How did the momentum feel?

Does the ending surprise and satisfy you? What do you think might happen next?

What about grammar and mechanics? At this point, a beta reader might comment on whether or not you have a basic understanding of grammar and industry practices that suits your genre.

I am fortunate to have excellent friends willing to do this for me. Their suggestions are thoughtful and spot-on.

Editing is a process unto itself and is the final stage of making revisions. The editor goes over the manuscript line-by-line, pointing out areas that need attention: awkward phrasings, grammatical errors, missing quotation marks—many things that make the manuscript unreadable. Sometimes, major structural issues will need to be addressed. Straightening out all the kinks may take more than one trip through a manuscript.

Editing is a process unto itself and is the final stage of making revisions. The editor goes over the manuscript line-by-line, pointing out areas that need attention: awkward phrasings, grammatical errors, missing quotation marks—many things that make the manuscript unreadable. Sometimes, major structural issues will need to be addressed. Straightening out all the kinks may take more than one trip through a manuscript.

There are different kinds of editing, as the various branches of literature have requirements that are unique to them. In creative writing, editing is a stage in which a writer and editor work together to improve a draft by ensuring consistency in style and grammatical usages.

The editor does not try to change an author’s voice but does point out errors. When an author’s style goes against convention and it is their choice, the editor ensures it does so consistently from page one to the end of the manuscript. At the same time, attention is paid to transitions and the overall story arc.

Proofreading is its own thing.

A good proofreader understands that the author has already been through the editing gauntlet with that book and is satisfied with it in its current form. A proofreader will not try to hijack the process and derail an author’s launch date by nitpicking their genre, style, and phrasing.

A good proofreader understands that the author has already been through the editing gauntlet with that book and is satisfied with it in its current form. A proofreader will not try to hijack the process and derail an author’s launch date by nitpicking their genre, style, and phrasing.

The proofreader must understand that the author has hired a professional line editor and is satisfied that the story arc is what they envisioned. The author is confident that the characters have believable and unique personalities as they are written. The editor has worked with the author to ensure the overall tone, voice, and mood of the piece is what the author envisioned.

I used the word ‘envisioned‘ twice in my previous paragraph because the work is the author’s creation, a product of their vision. By the time we arrive at the proofing stage, the prose, character development, and story arc are intentional. The author and their editor have considered the age level of the intended audience.

If you feel the work is too dumbed down or poorly conceived and you can’t stomach it, simply hand the manuscript back and tell them you are unable to do it after all.

If you have been asked to proofread a manuscript, please DON’T mark it up with editorial comments. Don’t critique their voice and content because it will be a waste of time for you and the author.

- And, if your comments are phrased too harshly at any point during this process, you could lose a friend.

If the person who has agreed to proof your work cannot refrain from asking for significant revisions regarding your style and content, find another proofreader, and don’t ask them for help again.

The problem that frequently rears its head among the Indie community occurs when an author who writes in one genre agrees to proofread the finished product of an author who writes in a different genre. People who write sci-fi or mystery often don’t understand or enjoy paranormal romances, epic fantasy, or YA fantasy.

The problem that frequently rears its head among the Indie community occurs when an author who writes in one genre agrees to proofread the finished product of an author who writes in a different genre. People who write sci-fi or mystery often don’t understand or enjoy paranormal romances, epic fantasy, or YA fantasy.

Also, some people can’t proofread because they are fundamentally driven to critique and edit.

Indies must hope their intended proofreader is aware of what to look for. In traditional publishing houses, proofreading is done after the final revisions have been made. Hopefully, it is done by someone who has not seen the manuscript before. That way, they will see it through new eyes, and the small things in your otherwise perfect manuscript will stand out.

What The Proofreader Should Look For:

Spelling—misspelled words, autocorrect errors, and homophones (words that sound the same but are spelled differently). These words are insidious because they are real words and don’t immediately stand out as being out of place. The human eye is critical for this.

- Wrong: There cat escaped, and he had to chase it.

- Wrong: The dog ran though the house

- Wrong: He was a lighting.

Repeated words and cut-and-paste errors. These are sneaky and dreadfully difficult to spot. Spell-checker won’t always find them. To you, the author, they make sense because you see what you intended to see. For the reader, they appear as unusually garbled sentences.

Repeated words and cut-and-paste errors. These are sneaky and dreadfully difficult to spot. Spell-checker won’t always find them. To you, the author, they make sense because you see what you intended to see. For the reader, they appear as unusually garbled sentences.

- Wrong: It is accepted thoughts italicize thoughts.

Missing punctuation and closed quotes:

- Wrong: “What do you know about the dead man? asked Officer Shultz.

Numbers that are digits:

Miss keyed numbers are difficult to spot when they are wrong unless they are spelled out.

- Wrong number: There will be 30000 guests at the reception.

Dropped and missing words:

- Wrong: Officer Shultz sat at my kitchen table me gently.

I have to be extra vigilant when making corrections my proofreader has asked for. Each time I change something in my already-edited manuscript, I run the risk of creating another undetected error.

At some point, your manuscript is finished. Your beta readers pointed out areas that needed work. The line editor has beaten you senseless with the Chicago Manual of Style. The content and structure are as good as you can get them. Your proofreader has found minor flaws that were missed.

At some point, your manuscript is finished. Your beta readers pointed out areas that needed work. The line editor has beaten you senseless with the Chicago Manual of Style. The content and structure are as good as you can get them. Your proofreader has found minor flaws that were missed.

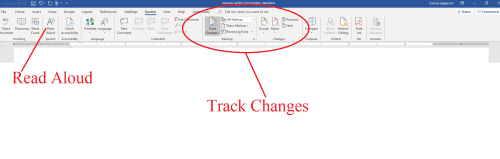

If you don’t have access to a proofreader, there is a way to proof your own work. I find that making a printout of each chapter and reading it aloud helps me to see the flaws I have missed when reading my work on the screen. I hope this helps you on your writing journey!

CREDITS/ATTRIBUTIONS:

The Passion of Creation, Leonid Pasternak [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Writing letter, By Kusakabe_Kimbei [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Today we are discussing a particular kind of editor: the submissions editor. When I first began this journey, I didn’t understand how specifically you have to tailor your submissions for literary magazines, contests, and anthologies. Each publication has a specific market of readers, and their editors look for new works their target market will buy.

Today we are discussing a particular kind of editor: the submissions editor. When I first began this journey, I didn’t understand how specifically you have to tailor your submissions for literary magazines, contests, and anthologies. Each publication has a specific market of readers, and their editors look for new works their target market will buy. The quality of your work isn’t the problem, and you have selected a publication that features work in your chosen genre. But your subgenre may not match what the readers of that publication want to see. After all, both spaghetti Bolognese and bruschetta are created out of ingredients made from wheat and tomatoes, but the finished meals are vastly different.

The quality of your work isn’t the problem, and you have selected a publication that features work in your chosen genre. But your subgenre may not match what the readers of that publication want to see. After all, both spaghetti Bolognese and bruschetta are created out of ingredients made from wheat and tomatoes, but the finished meals are vastly different. Some hobbyists expect special consideration and are offended when they don’t get it. Egos are rampant in this business, but in reality, no one gets to be treated like a princess.

Some hobbyists expect special consideration and are offended when they don’t get it. Egos are rampant in this business, but in reality, no one gets to be treated like a princess. er sending your work.

er sending your work. Please, if you consider yourself a professional, format your submissions properly. You want to stand out but getting fancy with your final manuscript is not the way to do that—you will be rejected out of hand if you don’t make this effort.

Please, if you consider yourself a professional, format your submissions properly. You want to stand out but getting fancy with your final manuscript is not the way to do that—you will be rejected out of hand if you don’t make this effort. Most editors will ask to see the first twenty pages of your manuscript before they agree to accept the job. Sometimes, significant issues will need to be addressed. If so, an editor will probably refuse to accept your manuscript. However, they will tell you why and give you pointers on how to resolve the problems.

Most editors will ask to see the first twenty pages of your manuscript before they agree to accept the job. Sometimes, significant issues will need to be addressed. If so, an editor will probably refuse to accept your manuscript. However, they will tell you why and give you pointers on how to resolve the problems. For new and beginning authors, it may take an editor more than one trip through a manuscript to straighten out all the kinks. This may be a three-step process involving you making the first round of revisions and/or explanations, sending them back to the editor, who will make final round of suggestions. At that point, the editor is done. You have the choice to either accept or reject those suggestions in your final manuscript.

For new and beginning authors, it may take an editor more than one trip through a manuscript to straighten out all the kinks. This may be a three-step process involving you making the first round of revisions and/or explanations, sending them back to the editor, who will make final round of suggestions. At that point, the editor is done. You have the choice to either accept or reject those suggestions in your final manuscript. For creative writing, editing is a stage of the writing process. A writer and editor work together to improve a draft by correcting punctuation and making words and sentences clearer, more precise. Weak sentences are made stronger, info dumps are weeded out, and important ideas are clarified. At the same time, strict attention is paid to the overall story arc.

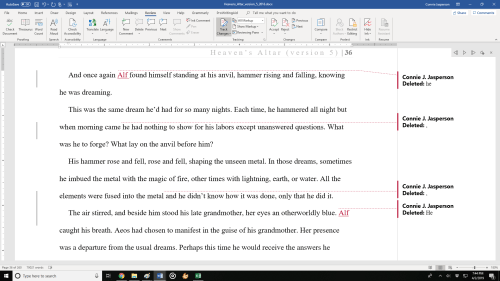

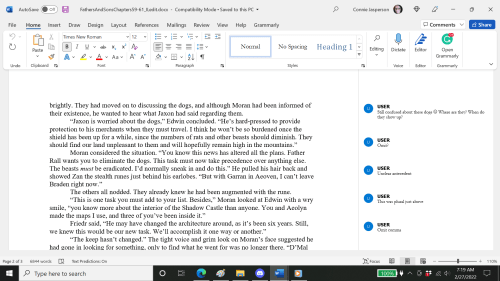

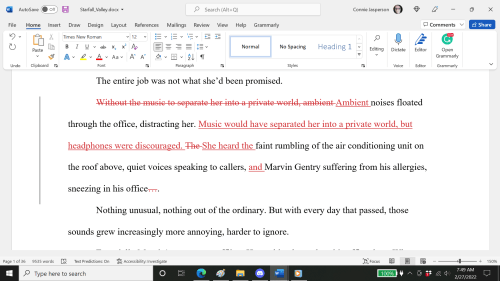

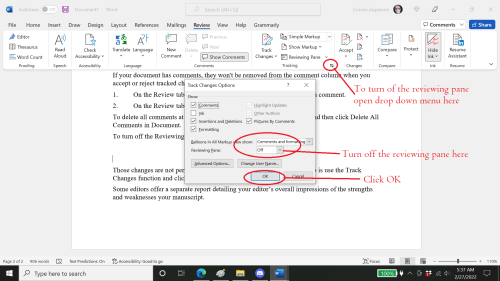

For creative writing, editing is a stage of the writing process. A writer and editor work together to improve a draft by correcting punctuation and making words and sentences clearer, more precise. Weak sentences are made stronger, info dumps are weeded out, and important ideas are clarified. At the same time, strict attention is paid to the overall story arc. Editors who have been in the business for a long time find it much faster to use the markup function and insert inline changes. A new author or someone unfamiliar with how word-processing programs work might find it confusing and difficult to understand.

Editors who have been in the business for a long time find it much faster to use the markup function and insert inline changes. A new author or someone unfamiliar with how word-processing programs work might find it confusing and difficult to understand. Inserting the changes and using Tracking cuts the time an editor spends on a manuscript. Writing comments takes time, and suggestions may not always be clear to the client.

Inserting the changes and using Tracking cuts the time an editor spends on a manuscript. Writing comments takes time, and suggestions may not always be clear to the client.

However, many authors don’t have the money to hire an editor. If that is the case, you may have a friend in your writing group who has some experience editing, and they will often help you at no cost. Your writing group is a well of inspiration, support, and wisdom, and they are invested in your book. They want you to succeed and most will gladly trade services.

However, many authors don’t have the money to hire an editor. If that is the case, you may have a friend in your writing group who has some experience editing, and they will often help you at no cost. Your writing group is a well of inspiration, support, and wisdom, and they are invested in your book. They want you to succeed and most will gladly trade services.