I was recently asked what I think the right chapter length should be in a novel. We haven’t talked about this in a while, so today is as good a day as any.

I like it when an author considers the comfort of their readers. Many readers, including me, want to finish a chapter in one sitting. We rarely have the time to sit and read all day, no matter that we wish we could.

I like it when an author considers the comfort of their readers. Many readers, including me, want to finish a chapter in one sitting. We rarely have the time to sit and read all day, no matter that we wish we could.

With that said, you must decide what your style is, and it will evolve as your writing career progresses.

Over the years, I’ve read and enjoyed many books where the authors made each scene a chapter, even if it was only two or three hundred words long. They ended up with over 100 chapters in their books, but because their story was so engaging, I barely noticed it.

In several seminars I’ve attended, the presenters suggested that we should have a specific word count limit for chapter length. One suggested 1500, while another said not more than 2500.

One of my favorite authors sometimes has chapters of only five or six hundred words, which keeps each character’s storyline separate and flows well. For my style of storytelling, 1,500 to 2,500 words is a good length.

As a reader, I have noticed that successful authors are careful to ensure that each chapter details the events of one scene or several closely related incidents. Chapters are like paragraphs in that cramming too many disparate ideas into one place makes the narrative feel erratic and disconnected.

As a reader, I have noticed that successful authors are careful to ensure that each chapter details the events of one scene or several closely related incidents. Chapters are like paragraphs in that cramming too many disparate ideas into one place makes the narrative feel erratic and disconnected.

My novel, Julian Lackland, has longer chapters. This is because the story arc details important events occurring over forty years of Julian’s life.

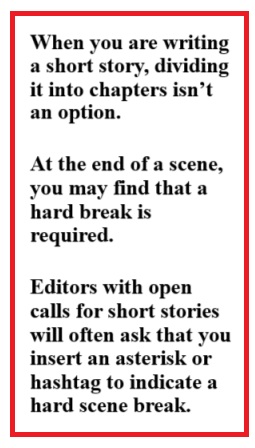

The novel follows the chronological order of his life, and the chapters detail the incidents that profoundly changed him. I inserted hard breaks within each chapter whenever a scene ended and a softer transition would have lent confusion to the narrative.

What is a soft transition? Conversations make good transitions to propel the story forward to the next scene. They also offer ways to end a chapter with a tidbit of information that will compel the reader to turn the page. Information is crucial, so we want to provide it when the protagonist and the reader require it.

Fade-to-black and hard scene breaks: I only use fade-to-black transitions as a finish to a chapter, as they leave the reader with something to think about.

Time must be considered too. When a real chunk of time has passed between the end of one scene and the beginning of the next, I suggest giving the scene a firm finish with a hook. That leads the reader to continue on to the next chapter.

Time must be considered too. When a real chunk of time has passed between the end of one scene and the beginning of the next, I suggest giving the scene a firm finish with a hook. That leads the reader to continue on to the next chapter.

With each scene, we push all the main characters forward and raise the stakes for each of them a little more. The action and dissemination of information entertain the reader. Good transitions allow the reader to reflect and absorb the information gained before moving on to the next scene.

This brings me to how the narrative point of view can influence the length of a scene or chapter. Some editors suggest you change chapters, no matter how short, when you switch to a different character’s point of view.

I (somewhat) agree with this stance, as a hard transition when you switch narrator-characters is the best way to avoid head-hopping and subsequent confusion.

But what is head-hopping? When you change the narrative point-of-view in the same scene, one paragraph to the next with no definite separation, you create a “viewpoint tennis match.”

First, you’re in Character A’s head hearing her thoughts, then you’re in Character B’s head hearing his. Then you’re back in A’s head. It becomes challenging to know who is speaking or thinking.

Also, the characters tend to lose their individuality. They begin to sound the same, further muddying the scene.

That is not to say that you should never switch viewpoints within a chapter. Sometimes, more than one character has a perspective that needs to be shown. However, readers will find it easier to follow the narrative if you are careful with how you handle the change of narrator.

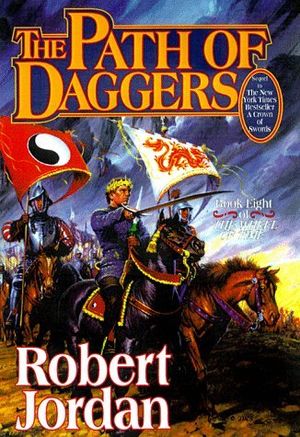

One of the problems some readers have with Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time Series is the way he wanders between storylines as if he couldn’t decide who the main character is. Rand al’Thor begins as the protagonist, but the narrative soon wanders far away from him as Matrim, Perrin, Nynaeve, Elayne, Aviendha, and Egwene are given prime storylines. Each thread comes together in the end, but this is the main criticism of the series.

One of the problems some readers have with Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time Series is the way he wanders between storylines as if he couldn’t decide who the main character is. Rand al’Thor begins as the protagonist, but the narrative soon wanders far away from him as Matrim, Perrin, Nynaeve, Elayne, Aviendha, and Egwene are given prime storylines. Each thread comes together in the end, but this is the main criticism of the series.

I’m a dedicated WoT fan, but even I found that exceedingly annoying by the time we reached book eight, Path of Daggers. I was halfway through reading that book when I realized there was a good chance that we would never see Rand do what he was reborn to do.

I try to concentrate on developing a single compelling, well-rounded main character, with the side characters well-developed but not upstaging the star. I kept reading the entire WoT series because Jordan’s (and later Sanderson’s) writing was brilliant, and the world and the events were intriguing.

It’s easier for the reader to follow the story when they are confined to one character’s perspective for the majority of the narrative. If you choose to switch POV characters, I suggest using a hard, visual break, such as two blank spaces between paragraphs or ending the chapter.

Now we come to a commonly asked question: Should I use numbers, or give each chapter a name?

What is your gut feeling for how you want to construct this book or series? If snappy titles pop up in your mind for each chapter, by all means, go for it. Otherwise, numbered chapters are perfectly fine and don’t throw the reader out of the book. Whichever style of chapter heading you choose, be consistent and stay with that choice for the entire book.

What is your gut feeling for how you want to construct this book or series? If snappy titles pop up in your mind for each chapter, by all means, go for it. Otherwise, numbered chapters are perfectly fine and don’t throw the reader out of the book. Whichever style of chapter heading you choose, be consistent and stay with that choice for the entire book.

To wind this up: Limit your point of view characters to one per scene. Each chapter should detail events that are related, rather than a jumble of unrelated happenings.

When it comes to chapter length, you must make the decision as to the right length and end chapters at a logical place. But do end each chapter with a hook that entices the reader to continue reading.

![I, Sailko [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/benozzo_gozzoli_corteo_dei_magi_1_inizio_1459_51.jpg?w=198&h=300)

![Sir Galahad, George Frederic Watts [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/220px-sir_galahad_watts.jpg?w=147&h=300)

![By Xpogo (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons Xpogo_Rio](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/xpogo_rio.png?w=300&h=197)