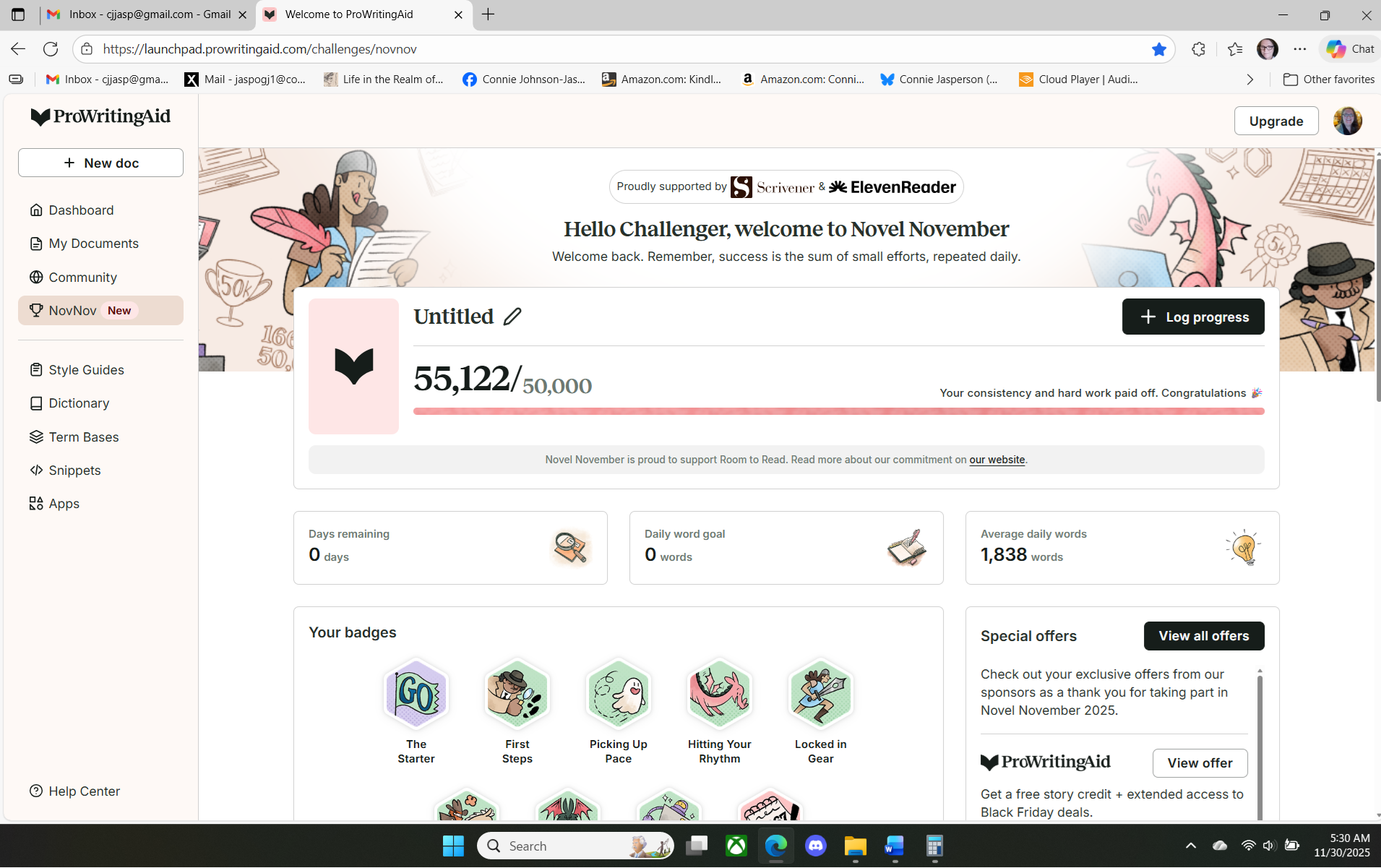

Today is the first day of December 2025. Over the last 30 days, I have written more than 50,000 words to finish the plot of a novel that is ½ of a duology. The story is too big and would make a giant doorstop of a book, so I am splitting it.

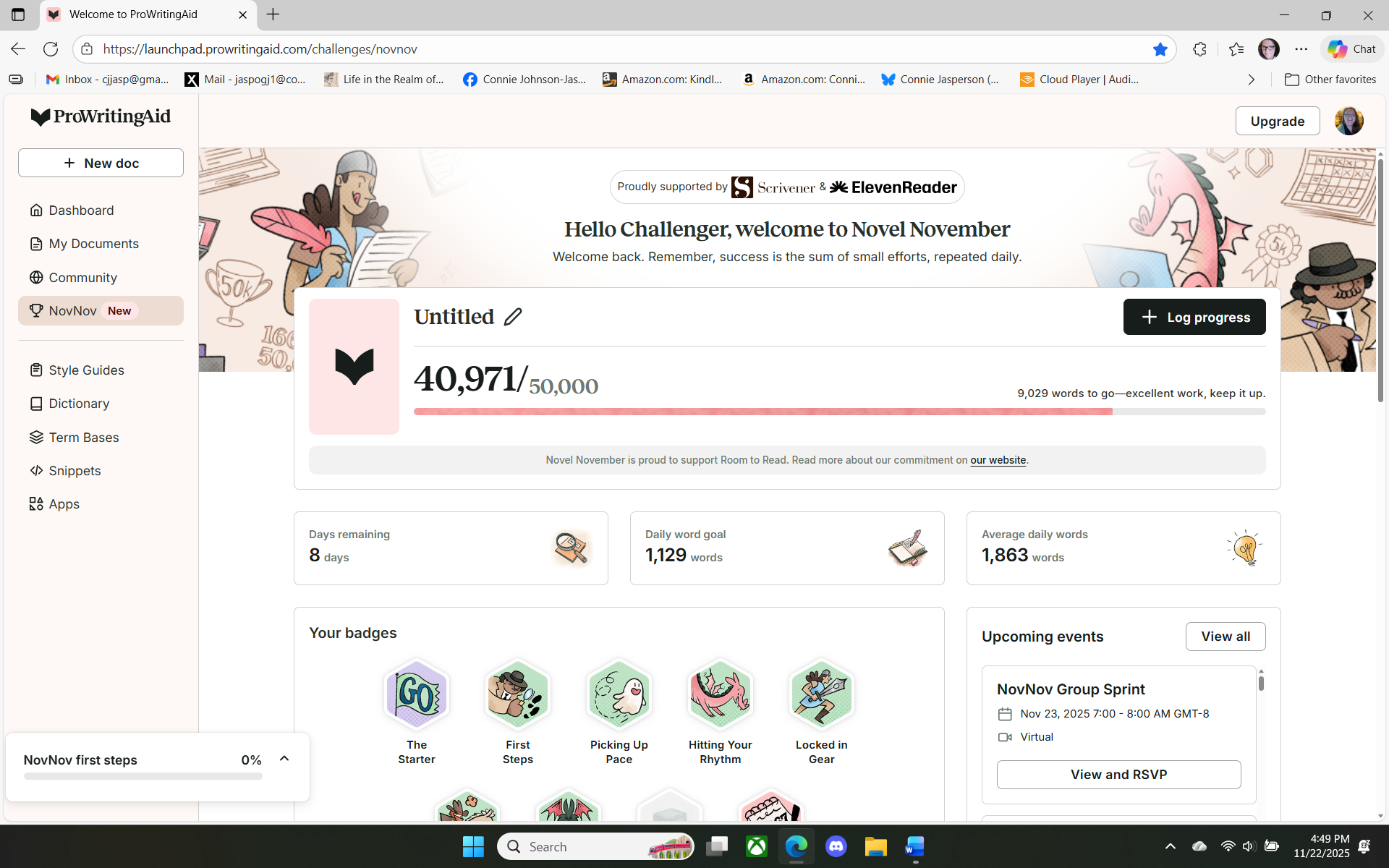

Book one is a complete first draft and desperately needs revising, but book two has barely begun. Here is the screenshot of my ProWritingAid’s NovelNovember dashboard yesterday, after I added my final wordcount for November.

I feel good about this experience, and I’ll probably do it again if they offer it next year.

I feel good about this experience, and I’ll probably do it again if they offer it next year.

As to my novel, I know how this story is supposed to end, as it is canon. The history mentioned in the series tells us that my protagonist is the founder of the Temple, and the College of Mages and Healers. The story told in these two books will end once my lovebirds clear the final hurdle to achieving those goals.

I have written the first draft of six complete chapters. It’s a good start in the main manuscript, so that is now at 16,010 words. I am now brainstorming the middle section in a separate manuscript. As of the time I am writing this post, that involves 39,112 words of thinking aloud and going back to the other books to ensure I don’t contradict myself.

Since I am rereading the main series that was published in my early days as a writer, I have found much that needs re-editing. Because I am an Indie, I can (and will) re-edit the entire series. I will do that whenever I am stalled on my current manuscript.

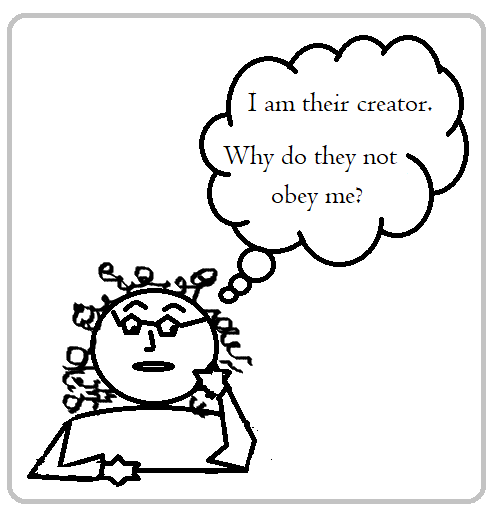

Unfortunately, the results of my written thinking aloud are good ideas that often don’t work for what I envision as the final product.

But they may become short stories set in that world. In the meantime, I have to make the answers to these two questions drive the plot:

- This is a continuation of the story that began in the previous book, so what do the characters want now that some of their goals have been achieved?

- What stands in the way of their achieving the final goal of defeating the Bull God’s stolen champion?

Thus, the background writing is moving along. I now have two major events to choreograph plot arcs for, and then I can connect the dots between my chosen scenes and give it an upbeat ending.

I do my mind-wandering in a separate document until I have concrete scenes. That brainstorming is productive because some of those rambles will become chapters.

The premise of books set in this world is that the gods are at war, and the world of Neveyah is the battleground. The gods cannot interact directly with each other or undo another god’s work, so the people of their worlds are the playing pieces, albeit pawns with free will and the option to struggle against their fate. My heroes and villains both see themselves as the protagonist because the fate of their world is at stake. There must be one god for each world, and the Bull God has imprisoned his brother in an attempt to steal his brother’s wife. He can’t kill Ariend but intends to claim Aeos and add their worlds to his. That was the Sundering of the Worlds, a catastrophic event nearly destroying three of the eleven worlds.

My heroes and villains both see themselves as the protagonist because the fate of their world is at stake. There must be one god for each world, and the Bull God has imprisoned his brother in an attempt to steal his brother’s wife. He can’t kill Ariend but intends to claim Aeos and add their worlds to his. That was the Sundering of the Worlds, a catastrophic event nearly destroying three of the eleven worlds.

Now, a thousand years have passed and he is once again on the move. If the protagonist wins, the Goddess of Hearth and Home will retain control of Ariend’s prison and the world Aeos created. Conversely, if the antagonist wins, the Bull God will claim it all, and the imbalance of the worlds will once again threaten the stability of their universe.

So, now I’m plotting the midpoint crisis. An important festival and a council of elders is held. My protagonist must work to sway the skeptics in his direction. In their personal arcs, he and his wife must overcome their own doubts and fears and make themselves stronger.

So, now I’m plotting the midpoint crisis. An important festival and a council of elders is held. My protagonist must work to sway the skeptics in his direction. In their personal arcs, he and his wife must overcome their own doubts and fears and make themselves stronger.

Then I must work on fleshing out the enemy. This mage is not a terrible person. Once a devoted follower of Aeos, he triggered a mage trap and was forcibly converted to the enemy’s side.

Now he is under an unbreakable spell and his loyalty is given to the Bull God, the Breaker of the Worlds. The god manipulates him. My antagonist’s motives stem from his imposed conviction that the Goddess is weak and that the tribes have strayed from the traditions that made them strong.

My antagonist is featured three times briefly in the first half of this tale. That story is devoted to the protagonist surviving several events that give rise to the tales that turn an ordinary warrior-shaman into the legendary hero the children’s books say he was. Now, I must write my antagonist with empathy because his fall from grace was a tragedy and a terrible personal loss to our protagonist.

Both intend to prevail at any cost. What is the final hurdle, and what will the characters lose in the process? Is the price physical suffering or emotional? Or both? This is an origin story, so history tells me who succeeds. But what is the personal cost of that success?

I know my protagonist and antagonist will meet in a large battle, face to face. Several people we love will die, enabling the desired ending. I know who must die, and I have an idea of where that will happen, because whenever I have a thought about any aspect of this story, I write it down.

I know my protagonist and antagonist will meet in a large battle, face to face. Several people we love will die, enabling the desired ending. I know who must die, and I have an idea of where that will happen, because whenever I have a thought about any aspect of this story, I write it down.

By the end of this book, all the threads that began in book one will have been drawn together and resolved for better or worse.

In real life, people live happily, but no one lives a deliriously happy-ever-after. Thus, the ending must be finite and wrap up the conflict. The future must look rosy for my protagonist and his companions.

Thank you all for listening to me rant about my work. What is your project and how is it progressing? What has been your greatest struggle?

Sometimes writing is a lonely craft. It helps to have a writing group to talk to. They help me reframe ideas in a way that works better than my original plan. And when it gets to the beta reading stage, they will be there with good suggestions.