Note to self: write dynamic prose and avoid crutch words.

One thing I notice when listening to an audiobook is crutch words. One of my favorite authors uses the descriptor “wry” in all its forms, just a shade too frequently. As a result, I have scrubbed it from my own manuscript, except for one instance.

One thing I notice when listening to an audiobook is crutch words. One of my favorite authors uses the descriptor “wry” in all its forms, just a shade too frequently. As a result, I have scrubbed it from my own manuscript, except for one instance.

Wry is a modifier. It means using or expressing dry, especially mocking, humor: “a wry smile.”

“Sardonic,” a word he also uses a bit too frequently, is a relative of the word “wry” and means grimly mocking or cynical.

Both are good words, but they are easily overused when we are trying to show a character’s mood in a bleak situation.

Grin and smile are also first draft crutch words we use to show a mood. I do a global search and then tear my hair out trying to show my protagonist’s mood without getting hokey.

The way we use modifiers and descriptors (and their frequency) plays a significant role in how our work is received by a reader.

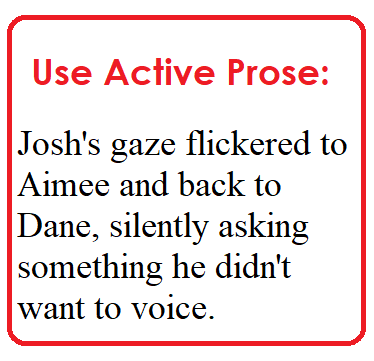

The words authors choose add depth and shape their prose in a recognizable way—their voice. They “paint” a scene showing what the point-of-view character sees or experiences.

The words authors choose add depth and shape their prose in a recognizable way—their voice. They “paint” a scene showing what the point-of-view character sees or experiences.

And yes, in order to do that, they must use modifiers and descriptors, also known as adjectives and adverbs.

Modifiers are like any other medicine: a small dose can cure illnesses. A large dose will kill the patient. The best use of them is to find words that convey the most information with the most force.

What do we mean when we refer to modifiers?

A modifier is any word that modifies (alters, changes, transforms) the meaning and intent of another word. These words change, clarify, qualify, or limit a particular word in a sentence to add emphasis, explanation, or detail.

Some of these words are useful as conjunctions, words to connect thoughts: “otherwise,” “then,” and “besides.”

What are descriptors? Adverbs and adjectives, known as descriptors, are helper nouns or verbs—words that help describe other words.

What are descriptors? Adverbs and adjectives, known as descriptors, are helper nouns or verbs—words that help describe other words.

What is a quantifier? They are nouns (or noun phrases) meant to convey a vague number or an abstract impression, such as very, a great deal of, a good deal of, a lot, many, much. The important word there is abstract. It is a thought or idea describing something without physical or concrete existence.

Modifiers, descriptors, and quantifiers are easily overused, so these words are often reviled by authors armed with a little dangerous knowledge.

One of the cautions those of us new to the craft frequently hear are criticisms about the number of “ly” words we habitually use. The forms we use can weaken our narrative.

First, examine the context. Have you used the word “actually” in a conversation? You may want to keep it, as dialogue must sound natural, and many people use that word when speaking.

However, if you have used “actually” to describe an object, take a second look to see if it is necessary.

However, if you have used “actually” to describe an object, take a second look to see if it is necessary.

- The tree was actually covered in red leaves.

Would the sentence be stronger without it?

- Red leaves covered the tree.

Some descriptors are easy to spot, especially those ending in “ly.” When I begin revising a first draft, I do a global search for the letters “ly.” A list will pop up in my lefthand margin. My manuscript will become a mass of yellow highlighted words.

This is where I look at each instance because “ly” words are code words the subconscious mind uses in the first draft. They are a kind of mental shorthand that tells us what we need to expand on to fully explore the scene we envisioned.

Or they tell me something needs to be cut.

Context is everything. Please take the time to look at each example of the offending words and change them individually. I’ve said this many times, but I like to nag: You have already spent months writing that novel. Why not take a few days to do the job well?

Sentence structure matters. The placement of an adjective in relation to the noun it describes affects a reader’s perception. Modifiers often work best when showing us what the point-of-view characters see, hear, smell, touch, and taste.

Sunlight glared over the ice, a cold fire that cast no warmth but burned the eyes.

In the above sentence, the essential parts are structured this way: noun – verb (sunlight glared), adjective – noun (cold fire), verb – adjective – noun (cast no warmth), and finally, verb – article – noun (burned the eyes).

So, we try to lead with the action or noun, followed by a strong modifier (one without the “ly” ending). The sentence conveys what is intended. It has modifiers but isn’t weakened by them.

The scene I detailed above could be shown in many ways. I took a paragraph’s worth of world-building and pared it down to 19 words, three of which are action words.

The scene I detailed above could be shown in many ways. I took a paragraph’s worth of world-building and pared it down to 19 words, three of which are action words.

So, now you know what occupies most of my attention during revisions.

As writers, we all want to be accepted and have others like our work, which means we must meet our reader’s expectations.

Writers must write from the heart, or there is no joy in writing.

That means using modifiers, descriptors, or quantifiers when they are needed. It’s a balancing act. We must be mindful of the form and the context of how a modifier fits into our phrasing.

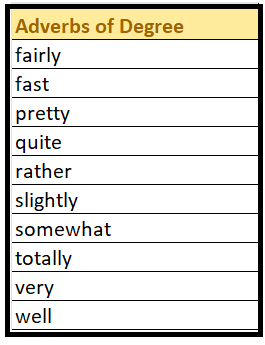

Below are two images. They are lists of code words I seek out and re-examine when I begin revising a first draft. Some words are quantifiers. They are adverbs of degree, words that describe how much of something, such as “I’m dreadfully unhappy.” Quantifiers (also known as adverbs of degree) have their place but can weaken a sentence. So, they are code words for you to look closely at when you get to the revision stage.

“Adverbs of manner” are qualifiers, words that “qualify the manner of what we are talking about.” They can intensify or decrease the degree of something, such as “I rarely go out.”

It seems like an overwhelming task, but it isn’t. I look at each instance of a modifier and see how it fits into that context. If a word or phrase weakens the narrative, I rewrite the sentence. I either change it to a more straightforward form or remove it. For example, bare is an adjective, as is barely. Both can be used to form a strong image, depending on the words we surround them with.

I have found that participating in a critique group has been crucial to my growth as an author. Most writing groups are made up of people who love reading and want your work to succeed. They won’t micromanage your manuscript because they are aware that too much input can remove the author’s unique voice from a piece.

Credits and Attributions:

IIMAGE: Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:2014-10-30 11 09 40 Red Maple during autumn on Lower Ferry Road in Ewing, New Jersey.JPG,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:2014-10-30_11_09_40_Red_Maple_during_autumn_on_Lower_Ferry_Road_in_Ewing,_New_Jersey.JPG&oldid=751843290 (accessed April 28, 2024).

An excellent post, Connie. I am often guilty of overusing some words. Search about to begin for those pesky -ly words!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, V! Scrubbing crutch words from my manuscript feels exhausting. I hope you have a great week!

LikeLike

‘…context is everything…’ Absolutely. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello, and thank you!

LikeLike