This last week, I edited a paper that my grandson had to submit to his literature class at his college. That experience sparked the realization that many people make it all the way through school without learning even a few of the more common rules for punctuating written English.

Yet many of these people have stories they are bursting to write. But they are embarrassed to share them. Or perhaps they shared their first attempt with someone who either brushed them off or was harshly critical.

Yet many of these people have stories they are bursting to write. But they are embarrassed to share them. Or perhaps they shared their first attempt with someone who either brushed them off or was harshly critical.

Many authors just out of school know they lack knowledge of punctuation mechanics but feel unworthy and a little traumatized. They don’t know where to get the information they need. If that is your situation, I have compiled a list of 7 easy-to-remember rules of punctuation, which was posted on May 26, 2025.

Feel free to bookmark that post and refer back to it as needed.

I have learned a great deal by reading the Chicago Manual of Style. It’s a behemoth of a book. Just the thought of reading, much less understanding this doorstop, is daunting to a new writer, and the price for the latest hardcover version is steep.

However, if you learn the seven basic rules discussed in my May 26th post, your work will be acceptable to most people. I will add links to several other good, affordable books on craft at the end of this post.

First of all, good writing conveys the most information with no unnecessary words. Bad writing is not a sin, if we understand that many problems can be resolved in the second draft, the stage known as revisions.

Passive phrasing, skipped punctuation, and garbled cut-and-paste issues are all codes for the author. The overuse of modifiers and descriptors are first-draft signals that tell us what we need to rephrase or show more clearly.

For example:

-

The tree was actually covered in red leaves.

This is a simple, passively phrased sentence, but it is properly punctuated. The sentence begins with a capital letter, as it should, and ends with a period (full stop). However, it is an example of bad writing, the kind of thing we lay down in the first draft when we are just trying to get the whole story down.

It is passive rather than active, and the word “actually” isn’t necessary.

-

Red leaves covered the tree.

The revision expresses the same idea, using many of the same words. It is active, and by rephrasing it, we conveyed the same idea with fewer words. The author moved the noun and its descriptor (red leaves) to the front of the sentence, followed by the verb (covered) and the subject of the sentence (the tree). The author also removed the words “was” and “in” because they aren’t needed and would have fluffed up the word count.

- Using too many words to convey an idea leads to run-on sentences. It confuses the reader and makes what could be good scenes uninteresting.

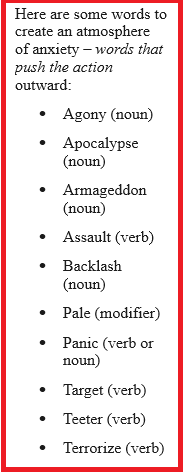

The order in which you place your words changes the tone of the narrative. When I begin revisions, I do a global search for “ly” words. I look at each instance and see how they fit into that context.

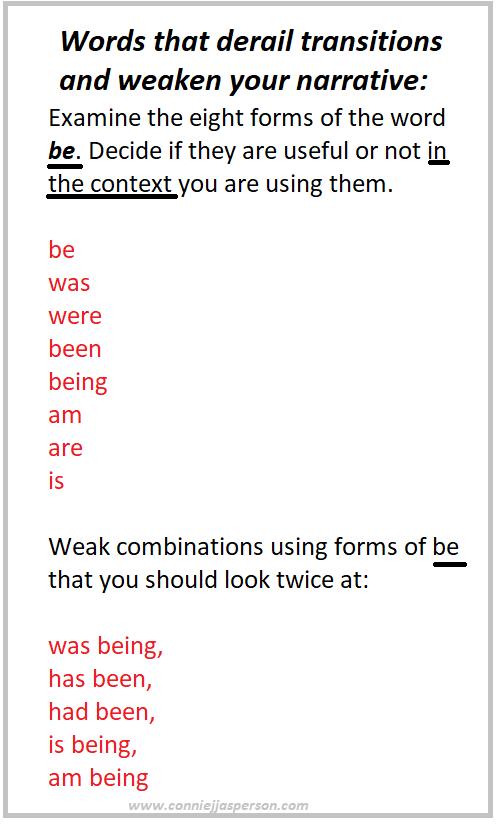

I also look for passive phrasing and the various forms of “to be,” such as was, were, and had been. They are needed in some places, but overuse of them weakens the prose.

If a word or phrase weakens the narrative, I change it to a simpler form or remove it and rewrite the sentence.

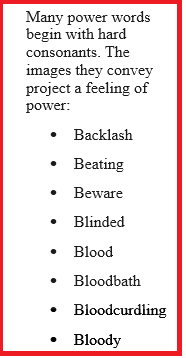

I DON’T recommend going through and getting rid of every adjective or adverb, although some gurus will say just that. They forget that words like bare are adjectives, and so is barely. Many descriptors and modifiers are power words.

I DON’T recommend going through and getting rid of every adjective or adverb, although some gurus will say just that. They forget that words like bare are adjectives, and so is barely. Many descriptors and modifiers are power words.

- If you take out the power words, you gut your prose.

- Also, words like every and very are part of larger words, such as everything. Cutting those words via a global search will ruin your manuscript.

Context is everything. Take the time to look at each example of the offending words and change them individually. You have already spent months writing that novel. Why not take a few days to do the job well?

Sentence structure matters. Where you place an adjective relative to the noun they are describing affects a reader’s perception. Adjectives work best when showing us what the point-of-view characters see, hear, smell, touch, and taste. The following sentence is an example I have used before:

Sunlight glared over the ice, a cold fire in the sky that cast no warmth but burned the eyes.

In the above sentence, the essential parts are structured this way: noun – verb (sunlight glared), adjective – noun (cold fire), verb – adjective – noun (cast no warmth), and finally, verb-article-noun (burned the eyes). Lead with the action or noun, follow with a strong modifier, and the sentence conveys what is intended but isn’t weakened by the modifiers.

The above scene could be shown in many ways, but a paragraph’s worth of world-building is pared down to 19 words, three of which are action words.

William Shakespeare understood the beauty and strength that powerful words written with minimal fluff can add to ordinary prose. Consider this line from his play, As You Like It, written in 1599:

It strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room. — As You Like It, Wm. Shakespeare, 1599.

What brilliant imagery Shakespeare employed in that sentence. He used strong words with powerful meaning: strikes, dead, great, reckoning, and little. Those words have visual impact. They convey emotion, which is what we all hope to do with our work.

What brilliant imagery Shakespeare employed in that sentence. He used strong words with powerful meaning: strikes, dead, great, reckoning, and little. Those words have visual impact. They convey emotion, which is what we all hope to do with our work.

As your reward for reading this post, here is the list of my current favorite books on the craft of writing. I suggest getting these in hardback, as it is much easier to find what you need. They can also be found used on Amazon, an option for cash-strapped authors.

To learn the basics:

The Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation ($11.99 US for Kindle, $22.11 hardcover). Great reference material at much lower cost than the Chicago Manual of Style, which runs around $55.00 or more.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms: ($5.99 Kindle, $19.99 hardcover). Find the alternatives to crutch words and learn to use them to the best effect.

To learn ways to fine-tune your manuscript:

Activate: a thesaurus of actions & tactics for dynamic genre fiction ($7.99 Kindle, $23.99 paperback). Written by Damon Suede, this is a great primer to help you write lean, descriptive prose.

Damn Fine Story ($15.99 Kindle, $18.99 paperback). Written by Chuck Wendig, this book is filled with information about how stories are constructed to help you write a cohesive narrative.

Another very interesting post, Connie! I think i have to restart learning the English language. There are so many things which I had not taken into account until now. Thanks also for the very useful book recommendations. Best wishes, Michael

LikeLiked by 1 person

hello, Michael! You speak English well and you are fluent and write well in your native language, so don’t worry too much. English is my native language, and even so, I have to work at retaining the information I was taught when I was young. 😀

LikeLike

Thanks for the honor, Connie! You hadn`t heard me speaking English, yet. Lol I better should have learned it in younger years. But now i am swallowing whatever i can get about better English reading, writing and speaking. 😉 Best wishes, Michael

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤

LikeLiked by 1 person