Narration is the use of a written or spoken commentary to convey a story to an audience. Wikipedia explains that a narrative consists of three components:

Narration is the use of a written or spoken commentary to convey a story to an audience. Wikipedia explains that a narrative consists of three components:

-

Narrative point of view: the perspective (or type of personal or non-personal “lens”) through which a story is communicated.

-

Narrative voice: the format (or type presentational form) through which a story is communicated.

-

Narrative time: the grammatical placement of the story’s time-frame in the past, the present, or the future.

We want to create a sense of intimacy, of being in the character’s head. One way to do that is to use stream of consciousness, a narrative mode that offers a first-person perspective by attempting to replicate the thought processes as well as the actions and spoken words of the narrative character.

This device incorporates interior monologues and inner desires or motivations, as well as pieces of incomplete thoughts that are expressed to the audience but not necessarily to other characters. Consider this passage from James Joyce’s Ulysses:

“A dwarf’s face, mauve and wrinkled like little Rudy’s was. Dwarf’s body, weak as putty, in a whitelined deal box. Burial friendly society pays. Penny a week for a sod of turf. Our. Little. Beggar. Baby. Meant nothing. Mistake of nature. If it’s healthy it’s from the mother. If not from the man. Better luck next time.

—Poor little thing, Mr Dedalus said. It’s well out of it.

The carriage climbed more slowly the hill of Rutland square. Rattle his bones. Over the stones. Only a pauper. Nobody owns.”

In this narrative mode, we see the POV character’s rambling thoughts, as well as witness their conversations and actions. This is a tricky device to do well, and the only time I have employed it was in a writing class.

When they want to tell a story though the protagonist’s eyes, many authors employ the first-person point of view to convey intimacy. With the first-person point of view, a story is revealed through the thoughts and actions of the protagonist within his or her own story. The waves carried me, and I fell upon the shore, a drowning man, clutching at the stones with a desperation I had never before known.

I have used first-person, and find it easy to write. I prefer to read a third-person narrative so that is what I write in most often.

If you prefer, as I do, to write in an omniscient voice, the story is told from an outside, overarching point of view. The narrator sees and knows everything that happens within the world of the story, including what each of the characters is thinking and feeling. A way to convey intimacy when writing in third person omniscient is to use the third-person subjective.

Again, Wikipedia says, “The third-person subjective is when the narrator conveys the thoughts, feelings, opinions, etc. of one or more characters. If there is just one character, it can be termed third-person limited, in which the reader is “limited” to the thoughts of some particular character (often the protagonist) as in the first-person mode, except still giving personal descriptions using “he”, “she”, “it”, and “they”, but not “I”. This is almost always the main character (e.g., Gabriel in Joyce’s The Dead, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Young Goodman Brown, or Santiago in Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea). Certain third-person omniscient modes are also classifiable as “third person, subjective” modes that switch between the thoughts, feelings, etc. of all the characters.”

This mode is also referred to as close 3rd person. I like this mode and frequently use it. At its narrowest and most subjective, the story reads as though the viewpoint character were narrating it. This is comparable to the first person, in that it allows an in-depth revelation of the protagonist’s personality, but differs as it always uses third-person grammar. Because it is always told in the third person, this is an omniscient mode. I like reading works written in this mode as it is easy for me as reader to form a deep attachment to the protagonist.

Some writers will shift perspective from one viewpoint character to another, such as George R. R. Martin does. I admit I don’t care for that but occasionally find myself falling into it. I then have to stop and make hard scene breaks, because it’s easy to fall into head-hopping, which is a serious no-no.

Head-hopping occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene and happens most frequently when using a Third-Person Omniscient narrative because the thoughts of every character are open to the reader.

Experiment with POV. Write a scene from one of your works in progress using a different narrative mode. You might be surprised what insights you will gain in regard to your own work.

Sources and Attributions:

Wikipedia contributors, “Narration,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Narration&oldid=777375141 (accessed May 7, 2017).

Quote from Ulysses, by James Joyce, published 1922 by Sylvia Beach

Wikipedia contributors, “Ulysses (novel),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ulysses_(novel)&oldid=777540958 (accessed May 7, 2017).

![Dragon By Linda BlackWin24 Jansson [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons Dragon-Linda_BlackWin24_Jansson](https://conniejjasperson.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/dragon-linda_blackwin24_jansson.jpg?w=266&h=300)

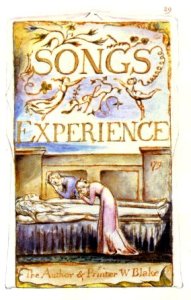

![[[File:Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy AA, object 1.jpg|Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy AA, object 1]] 384px-songs_of_innocence_and_of_experience_copy_aa_object_1](https://conniejjasperson.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/384px-songs_of_innocence_and_of_experience_copy_aa_object_1.jpg?w=192&h=300)

![[[File:William Blake - Death on a Pale Horse - Butlin 517.jpg|William Blake - Death on a Pale Horse - Butlin 517]] william_blake_-_death_on_a_pale_horse_-_butlin_517](https://conniejjasperson.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/william_blake_-_death_on_a_pale_horse_-_butlin_517.jpg?w=236&h=300)

![By Robertgrassi (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/villa_diodati_2008-07-27_rg_5.jpg?w=300&h=225)

However, that which was once canon regarding vampires is no longer set in stone.

However, that which was once canon regarding vampires is no longer set in stone. My main, desktop computer died on Saturday. It’s been limping along for a while. We had into the shop about six months ago, and should have known then it was terminal. The thing is, while I love Sturm und Drang in my literature, I prefer my electronic life to be stress-free.

My main, desktop computer died on Saturday. It’s been limping along for a while. We had into the shop about six months ago, and should have known then it was terminal. The thing is, while I love Sturm und Drang in my literature, I prefer my electronic life to be stress-free.