I have a favorite author, one who writes both sci-fi and fantasy. I really enjoy all his work, in both genres. However, I’m not going to name him because I am going to dissect what I love and don’t love about his work.

I never write a review for books I don’t love, and I have reviewed most, but not all, of his work. In this post, I’m going to point out things I notice with my editorial eye and which I want to avoid in my own work, so I’m not naming names.

I never write a review for books I don’t love, and I have reviewed most, but not all, of his work. In this post, I’m going to point out things I notice with my editorial eye and which I want to avoid in my own work, so I’m not naming names.

Let’s start by saying this: the things I don’t love about his work come from having a contract with deadlines to produce two books every year, installments for two widely differing series. That is a commitment he is well able to honor, as he has been publishing two and sometimes three a year since the late 1980s.

The upside of his meeting his deadlines is this: I get an installment in my favorite series every year.

But the downside is that he has a contract and deadlines he must meet.

First, let’s talk about what I like:

His main characters are engaging from page one. I’m always hooked and want to see where he is going to take them.

The main character always has a good arc of growth and is easy to like.

In most installments of my favorite series, the author’s worldbuilding is excellent. One can easily visualize the settings, whether we are in a future space environment or a world where magic exists. He creates mood and atmosphere with an economy of words.

In most installments of my favorite series, the author’s worldbuilding is excellent. One can easily visualize the settings, whether we are in a future space environment or a world where magic exists. He creates mood and atmosphere with an economy of words.

Science is always grounded in known and theoretical physics.

He has excellent systems for the two types of magic inherent in his fantasy world. They fit seamlessly into the story and feel plausible. They both have a learning curve, and even inadvertent misuse of magic can be lethal, so learning is required.

The societies in all his worlds, whether sci-fi or fantasy, are shown through the main character’s eyes. They are believable and feel personal.

What I don’t love about his work:

While I deeply enjoy his work, the author could use a sharp editor, one who’s not swamped with deadlines. The line editing is mostly adequate, but in recent books, one descriptor (sweetly) is used more than a few times and not to good advantage. “I thought so,” she said sweetly.

I dislike that phrasing because it diminishes the female love interest, making her sound a little snarky, as if she feels superior to the protagonist. I doubt that is the author’s intention, but that turn of phrase occurs more than a few times in more than one novel. Whether the main character is a man or a woman, the love interest is often two-dimensional, and this has been a thing throughout the last five or six books in this series.

I forgive that, because I like the main characters, the world, and love the plots.

Structurally, things can be a bit rough. The characters repeat what they have already done at every opportunity, covering old ground and stalling the momentum. Also, they frequently use the phrase “you deserve it” whenever the rewards of their accomplishments come up in conversation.

Structurally, things can be a bit rough. The characters repeat what they have already done at every opportunity, covering old ground and stalling the momentum. Also, they frequently use the phrase “you deserve it” whenever the rewards of their accomplishments come up in conversation.

The main flaw that is showing up in the most recent installments would be fatal in an Indie’s work. It is something that would be ironed out if our author had a full year to take his manuscript through revisions, rather than only six months. Each time the MC is introduced to someone, his accomplishments are brought up and discussed with awe. Whenever he runs into a fellow officer, which is fairly often, they have heard of his exploits through the grapevine and feel compelled to rehash them.

This is aggravating and slows the pacing.

Finally, proofing the finished product seems to have been rushed. This author has a big-name publisher, so one would think they would put a little effort into the final product.

Overall, this author’s work is good and deserves publication. None of these issues occurs often enough to derail the books, and a reader who isn’t a writer would likely never notice them. I can see how they flew under the radar.

It is important for authors to re-read the books they fall in love with. We rarely notice flaws on a first time through. If we do, we ignore them in favor of the story.

![]() When you read a beloved book a second time, look at it with a critical eye.

When you read a beloved book a second time, look at it with a critical eye.

Analyze what you like about the structure, worldbuilding, and character creation, and apply those principles to your work.

Recognize what doesn’t work and make notes when you come across something that slows the pacing or diminishes a character. Look for those flaws in your own work during revisions.

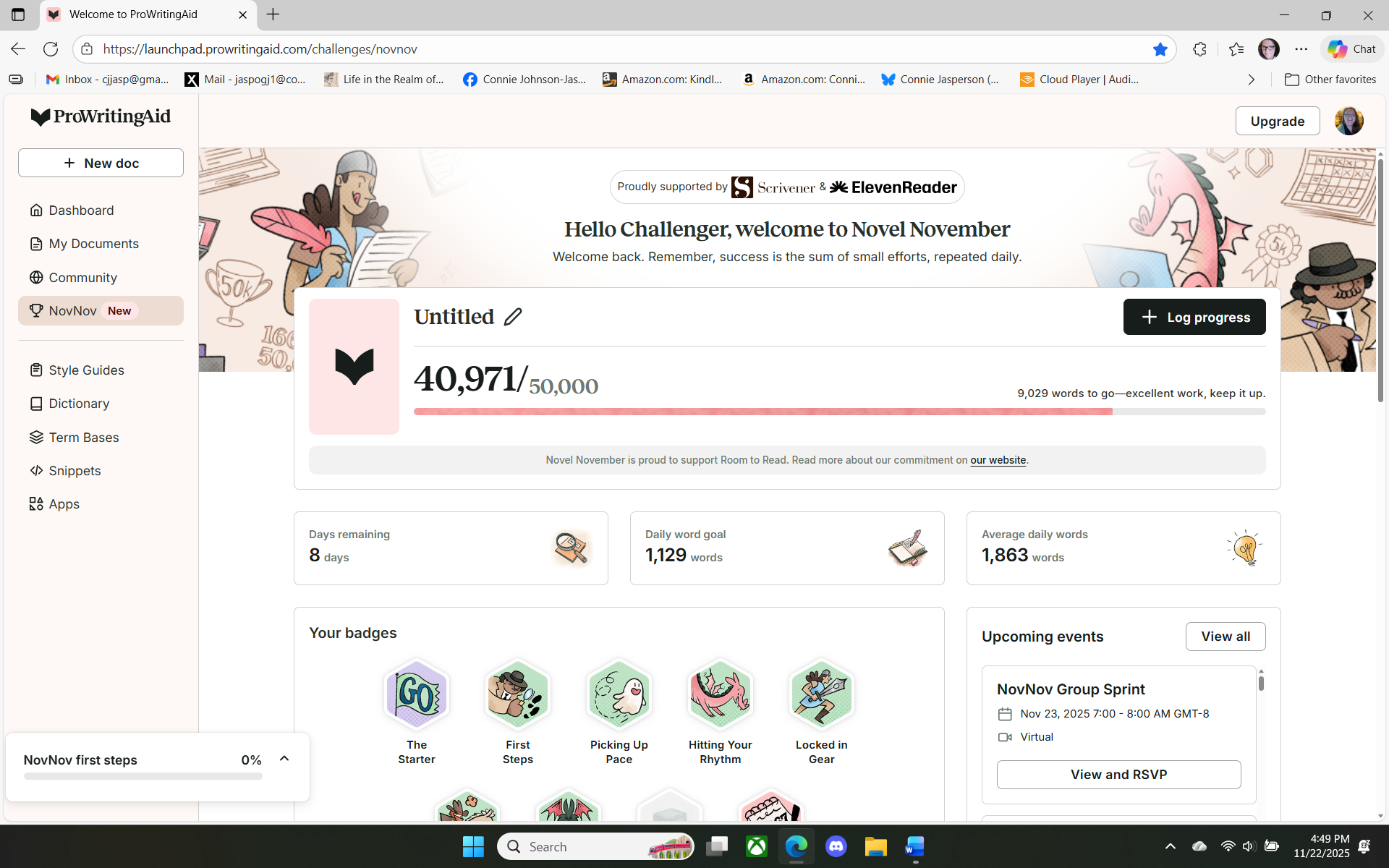

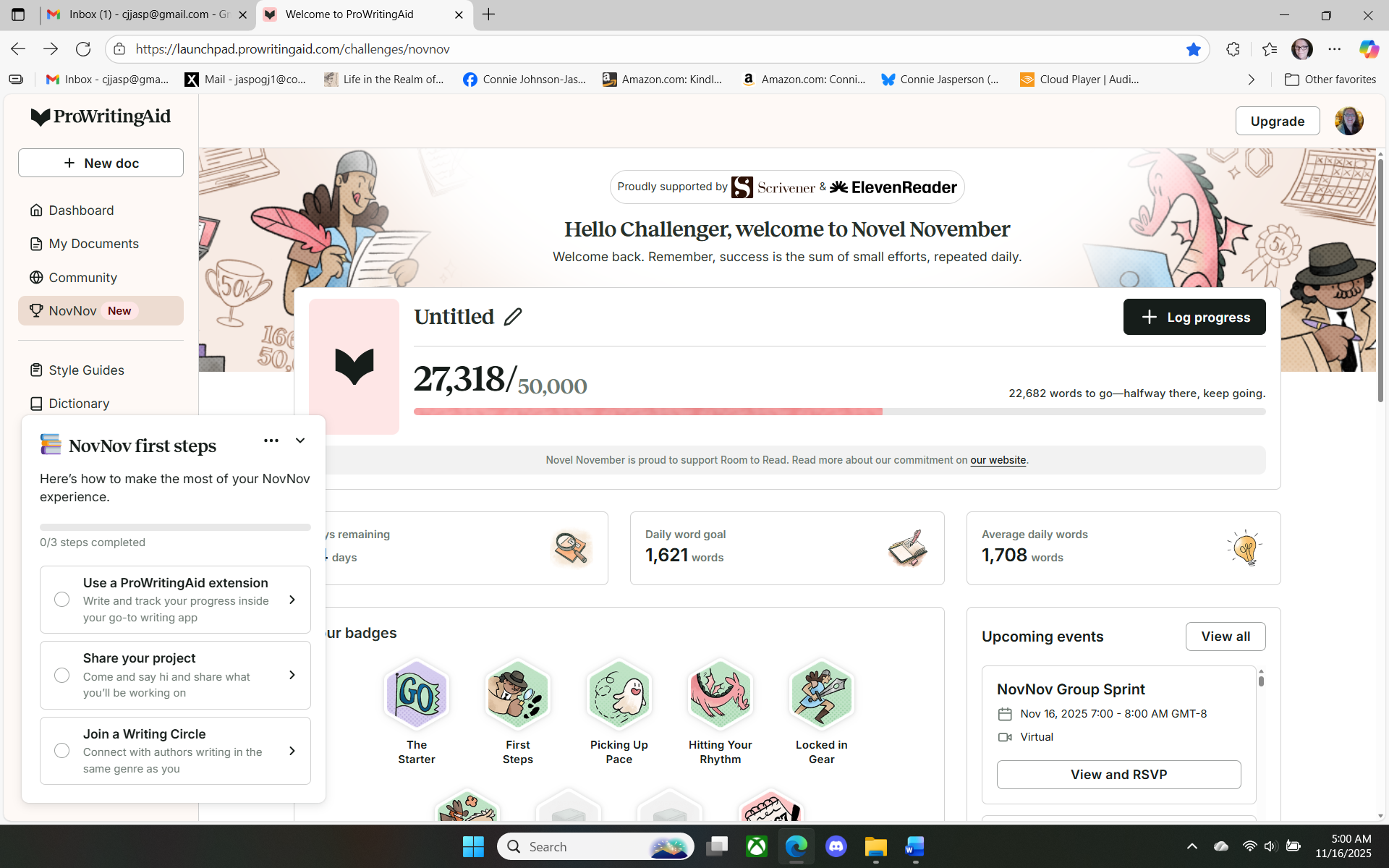

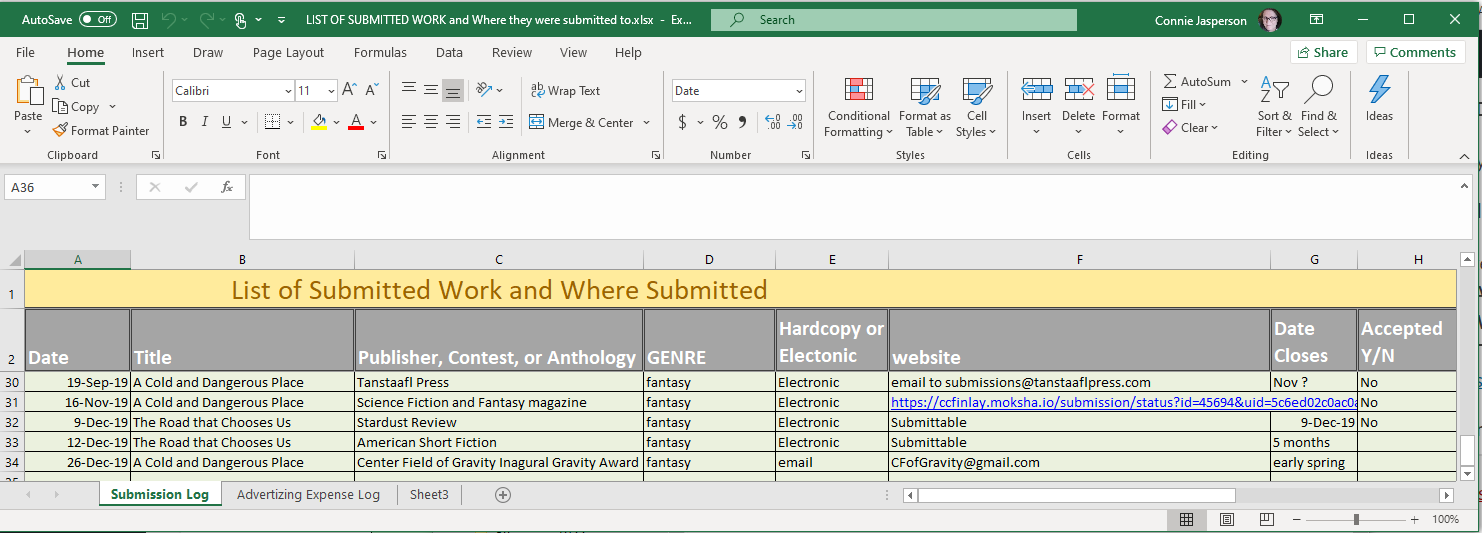

I have been making headway with my writing goals this November. Most of the plot is finalized, but it is still in outline form and will likely change as the story evolves.

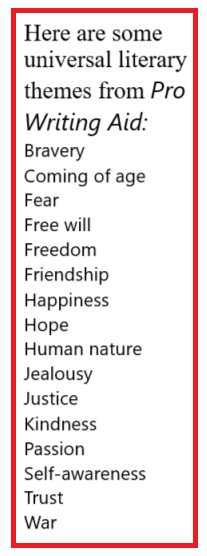

On Saturday, I crossed the 40,000-word mark at ProWritingAid’s Novel November. Most of what I’ve written (30,000 or so words) is background, stuff that won’t make it into the story but which helps me sort out the plot.

I have learned to write the background fluff in a separate document. When I begin filling out a now-skeletal plot, I have the information I need to flesh out a scene.

And hopefully, when I finally get this novel to the revisions stage, I will have an eye for the flaws. My writing group is sharp and when they beta read one of my manuscripts, they give me good advice.

The real trick is keeping the lid on my own repetitive words and gratuitous rehashing. Hopefully, in a year or two, my finished product will be a smooth read.