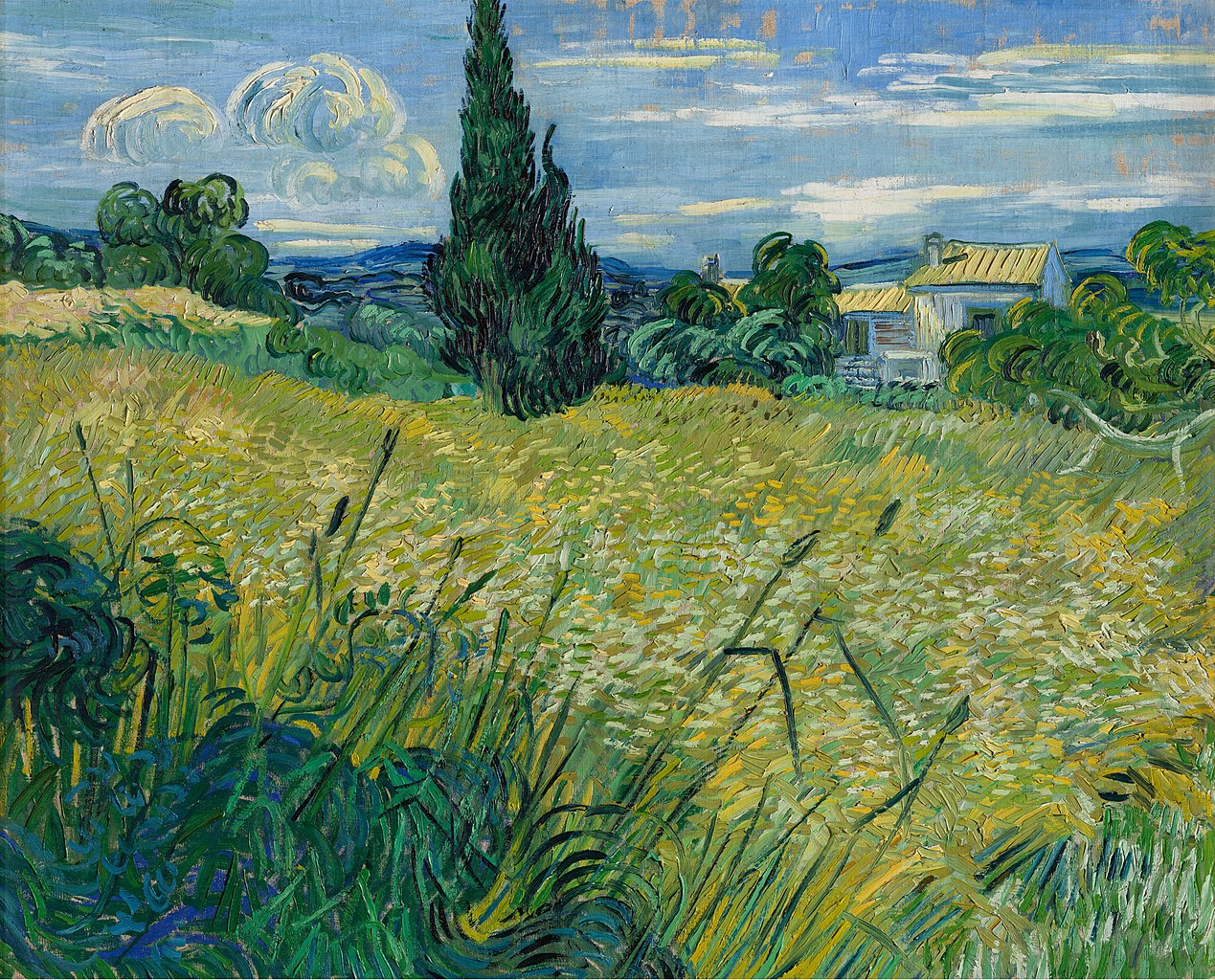

Artist: Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

Artist: Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

Title: Green Wheat Field with Cypress / Green Wheat

Date: mid June 1889

Medium: oil on canvas

Dimensions: height: 73 cm (28.7 in); width: 92.5 cm (36.4 in)

Collection: National Gallery Prague

What I love about this painting:

This painting is an example of the quintessential Vincent van Gogh view of his world. He shows us a sunny afternoon in swirls and strong colors, painting it the way he experienced it.

Vincent’s superpower was the ability to show us the emotions he felt as he painted a scene. In this case, I think he was feeling a sense of peace at being outdoors.

If you have stopped by this blog before, you know I am a writer. Art inspires me and I’m always imagining the story behind each painting I feature here. As a dedicated Vincent Fangirl, I can picture him having a good day, enjoying the harmony of a sunny afternoon in June, however fleeting those moments of peace were for him.

This painting was done one year before his suicide, during a brief a time when he was relatively happy, just before his final breakdown. The clouds, the blades of grass—each thing he saw that day is there, depicted with the emotions he experienced.

About this painting via Wikipedia:

The painting depicts golden fields of ripe wheat, a dark fastigiate Provençal cypress towering like a green obelisk to the right and lighter green olive trees in the middle distance, with hills and mountains visible behind, and white clouds swirling in an azure sky above. The first version (F717) was painted in late June or early July 1889, during a period of frantic painting and shortly after Van Gogh completed The Starry Night, at a time when he was fascinated by the cypress. It is likely to have been painted “en plein air“, near the subject, when Van Gogh was able to leave the precincts of the asylum. Van Gogh regarded this work as one of his best summer paintings. In a letter to his brother, Theo, written on 2 July 1889, Vincent described the painting: “I have a canvas of cypresses with some ears of wheat, some poppies, a blue sky like a piece of Scotch plaid; the former painted with a thick impasto like the Monticelli‘s, and the wheat field in the sun, which represents the extreme heat, very thick too.” [1]

Wheat fields via Wikipedia:

The wheat field with cypresses paintings were made when van Gogh was able to leave the asylum. Van Gogh had a fondness for cypresses and wheat fields of which he wrote: “Only I have no news to tell you, for the days are all the same, I have no ideas, except to think that a field of wheat or a cypress well worth the trouble of looking at closeup.”

In early July, Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo of a work he began in June, Wheat Field with Cypresses: “I have a canvas of cypresses with some ears of wheat, some poppies, a blue sky like a piece of Scotch plaid; the former painted with a thick impasto … and the wheat field in the sun, which represents the extreme heat, very thick too.” Van Gogh who regarded this landscape as one of his “best” summer paintings made two additional oil paintings very similar in composition that fall. One of the two is in a private collection. London’s National Gallery A Wheat Field, with Cypresses painting was made in September which Janson & Janson 1977, p. 308 describes: “the field is like a stormy sea; the trees spring flamelike from the ground; and the hills and clouds heave with the same surge of motion. Every stroke stands out boldly in a long ribbon of strong, unmixed color.”

There is also another version of Wheat Fields with Cypresses made in September with a blue-green sky, reportedly held at the Tate Gallery in London. [2]

About the Artist, via Wikipedia:

Vincent Willem van Gogh, 30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who posthumously became one of the most famous and influential figures in Western art history. In a decade, he created about 2,100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings, most of which date from the last two years of his life. They include landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and self-portraits, and are characterised by bold colours and dramatic, impulsive and expressive brushwork that contributed to the foundations of modern art. He was not commercially successful, struggled with severe depression and poverty, and committed suicide at the age of 37.

Van Gogh was born into an upper-middle-class family, While a child he drew and was serious, quiet and thoughtful. As a young man he worked as an art dealer, often traveling, but became depressed after he was transferred to London. He turned to religion and spent time as a Protestant missionary in southern Belgium. He drifted in ill health and solitude before taking up painting in 1881, having moved back home with his parents. His younger brother Theo supported him financially; the two kept a long correspondence by letter. His early works, mostly still lifes and depictions of peasant labourers, contain few signs of the vivid colour that distinguished his later work. In 1886, he moved to Paris, where he met members of the avant-garde, including Émile Bernard and Paul Gauguin, who were reacting against the Impressionist sensibility. As his work developed he created a new approach to still lifes and local landscapes. His paintings grew brighter as he developed a style that became fully realised during his stay in Arles in the South of France in 1888. During this period he broadened his subject matter to include series of olive trees, wheat fields and sunflowers.

Van Gogh suffered from psychotic episodes and delusions, and though he worried about his mental stability, he often neglected his physical health, did not eat properly and drank heavily. His friendship with Gauguin ended after a confrontation between the two when, in a rage, Van Gogh severed a part of his own left ear with a razor. He spent time in psychiatric hospitals, including a period at Saint-Rémy. After he discharged himself and moved to the Auberge Ravoux in Auvers-sur-Oise near Paris, he came under the care of the homeopathic doctor Paul Gachet. His depression persisted, and on 27 July 1890, Van Gogh is believed to have shot himself in the chest with a revolver, dying from his injuries two days later. [3]

Credits and Attributions:

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Vincent van Gogh – Green Wheat Field with Cypress (1889).jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Vincent_van_Gogh_-_Green_Wheat_Field_with_Cypress_(1889).jpg&oldid=670096634 (accessed March 13, 2025).

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Wheat Field with Cypresses,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wheat_Field_with_Cypresses&oldid=1222477822 (accessed March 13, 2025).

[2] Wikipedia contributors, “Wheat Fields,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wheat_Fields&oldid=1277932418 (accessed March 13, 2025).

[3] Wikipedia contributors, “Vincent van Gogh,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Vincent_van_Gogh&oldid=1279502999 (accessed March 13, 2025).

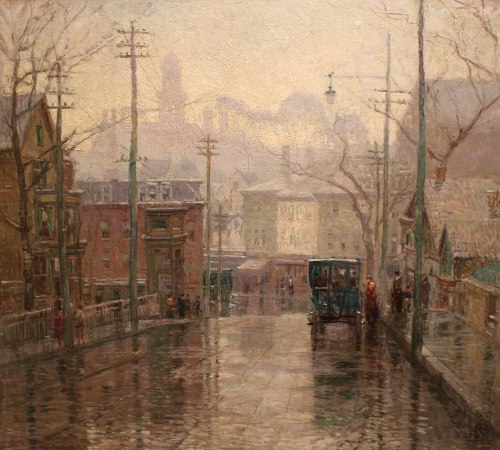

Title: After the Rain Gloucester

Title: After the Rain Gloucester