This week’s post is a reprint of a post on voice and how we phrase things. It first appeared here on February 17, 2020.

Writing is journey.

When I began writing, the way I placed my words slowed my prose, made it more passive. As I have grown, I have learned to place my verbs in such a way that the prose is more active. I say the same things, but my style is leaner than it was.

My weekend was spent with my hubby at the hospital (all is well now) and I had no time or inclination to write a new take on how word choices form our writing voice. I hope you enjoy this second look at one of my favorite subjects.

We are drawn to the work of our favorite authors because we like their voice. An author’s voice is the unique, recognizable way they choose words and assemble them into sentences.

With practice, we become technically better at the mechanics (grammar and punctuation) but our natural speech habits shine through. Voice is how we bend the rules and is our authorly fingerprint.

With practice, we become technically better at the mechanics (grammar and punctuation) but our natural speech habits shine through. Voice is how we bend the rules and is our authorly fingerprint.

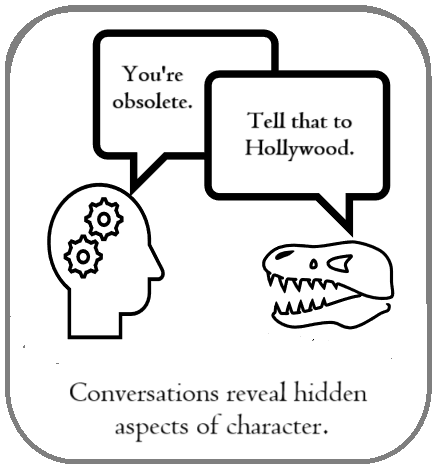

When we begin the editing process with a professional editor, most will ignore the liberties we take with dialogue but will point out our habitual errors in the rest of the narrative.

Many times, what we want to say is not technically correct, but we want that visual pause in that place, in that sentence. Casual readers who leave reviews will have gained some understanding of grammar but if your voice is consistent, they will accept your choice. However, they will notice inconsistencies and illiterate writing.

This is why the process of editing is so important. Knowledge of the mechanics of writing is crucial. If you don’t understand the rules, you can’t break them with authority. (For the first part of this series, see my post Revisions: Self-Editing.)

Consider Raymond Chandler’s dismay when he discovered his grammar had been heavily edited by a line editor and then published without his input in the corrections:

“By the way, would you convey my compliments to the purist who reads your proofs and tell him or her that I write in a sort of broken-down patois which is something like the way a Swiss waiter talks, and that when I split an infinitive, God damn it, I split it so it will stay split, and when I interrupt the velvety smoothness of my more or less literate syntax with a few sudden words of barroom vernacular, this is done with the eyes wide open and the mind relaxed but attentive. The method may not be perfect, but it is all I have.” – Raymond Chandler, in a letter to Edward Weeks, Editor of The Atlantic Monthly, dated 18 January 1947. (Read the letter in its entirety here.)

When we self-edit, we don’t have to wrestle for control of our work, true. But I have to be honest—I have worked with many editors over the past ten years, and only one tried to hijack my manuscript.

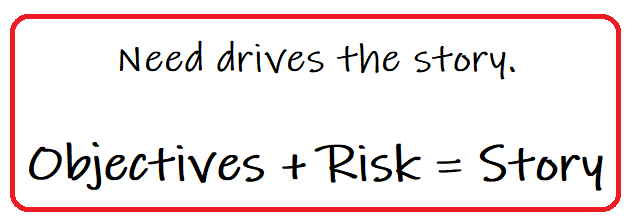

What is the mood you want to convey with your prose? Where you place the words in the sentence greatly affects the mood. Active prose is Noun-Verb centric. Compare these sentences, two of which are actively phrased, and two are passive. All say the same thing, and none are “wrong.”

I run toward danger, never away.

I never run away from danger.

Danger approaches, and I run to meet it.

If it’s dangerous, I run to it.

Can you tell which are passive and which are active? Which phrasing resonates with you? Could you write that idea in a different way?

Where we choose to place the core words, I run to danger, changes their voice but not their meaning. The words we choose to surround them with changes the mood but not their meaning.

Other ways to use the core concept of I run to danger:

Danger draws me. I race to embrace it, to make it mine.

If it’s dangerous or stupid, I will find it.

Danger—who cares. Running away is stupid; it always finds you. Meet it, grab it, and make it yours.

I saw him, and in that moment, I knew I’d met my destiny. He was the embodiment of danger, and I wanted him.

We could riff for half an hour on just four words, I run to danger. Each of us will write that idea with our own brand of brilliance, and none of us will sound exactly alike.

One of the things we must look at in our work is consistency. Is our narrative comprised of a smooth pattern? We don’t want our work to be jarring, so we want to think push, glide, push, glide.

Once you have established the mood you are trying to convey, look at how you have placed your verbs in the majority of your sentences.

Some are: noun – verb – modifier – noun. I run to danger when I see it. (Active)

Some are: infinitive – noun – verb – modifier – noun. When I see danger, I run toward it. (Passive)

NOTE: PASSIVE VOICE DOES NOT MEAN WRONG!

Good writing is about balance. How we combine active and passive phrasing is part of our signature, our voice. By mixing the two, we choose where we direct the reader’s attention.

Some work you want to feel highly charged, action-packed. Genres such as scifi, political thrillers, and crime thrillers need to be verb forward in the way the words are presented. These books seek to immerse the reader so more sentences should lead off with Noun – Verb, followed by modifiers.

If you clicked on the link and read Raymond Chandler’s letter in full, you will see it is aggressive and verb-forward, just the way his prose was.

In other genres, like cozy mysteries, you want to create a sense of comfort and familiarity of place with the mood. Perhaps you want to slightly separate the reader from the action to convey a sense of safety, of being an interested observer. You want the reader to feel like they are the detective with the objective eye, yet you want them immersed in the romance of it. To do that, you balance the active and passive sentence construction, so it is leaning slightly more toward the passive than a thriller.

Weak prose makes free with all the many forms of to be (is, are, was, were).

- He was happy.

- They were mad.

Bald writing tells only part of the story. For the reader to see and believe the entire story, we must choose words that show the emotions that underpin the story.

To grow in the craft, we learn to convey what we see through words.

Passive voice balances Active voice.

It is not weak, as weak prose distances the reader from the experience, and when active prose is interspersed with passive, it does not.

Voice is defined by word choice, and Passive or Active prose is defined by word placement, not how many words are used.

Weak prose usually uses too many words to convey an idea. So, we want to avoid wordiness no matter what mood we are trying to convey.

- One clue to look for is the overuse of forms of to be, which can lead to writing long, convoluted passages.

How many compound sentences do you use? How many words are in each sentence? Can you see ways to divide long sentences to make them more palatable?

How many compound sentences do you use? How many words are in each sentence? Can you see ways to divide long sentences to make them more palatable?

A wall of words turns away most readers. Look at your style, as you work your way through your revisions, and see what positive changes you can make in how you consistently phrase things.

Take a short paragraph from a work in progress and rewrite it. Try to convey that thought in both passive and active voice. Then blend the two. You might learn something about how you think as a writer when you try to write in an unfamiliar style.

The following is a list of words I habitually use in a first draft and then must look for in my own work. I look at each instance and decide if they work as they should or weaken the sentence. If they weaken the prose, I change or remove them.

Artist: Adolph Tidemand (1814–1876)

Artist: Adolph Tidemand (1814–1876)

Title: The Sycamores by Alexandre Calame

Title: The Sycamores by Alexandre Calame

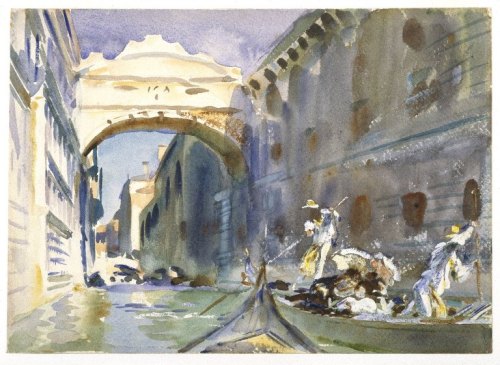

Artist: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)

Artist: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)

Artist:

Artist: