This last week I was asked what it takes for an ordinary person to be an author. My first thought was, no one is more ordinary than an author.

But I didn’t say that.

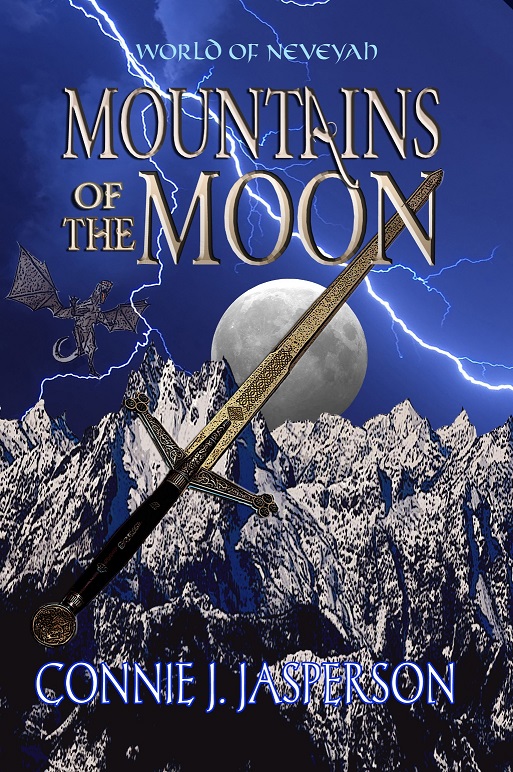

Authors are crafts folk, people who work at the craft of writing and take the time to turn out a finished product that is as good as we can make it. You wouldn’t enter a half-finished quilt at the county fair. You would go through all the steps to finish the job and take pride in your creation.

A serious writer takes the book through all the steps needed to make it readable, salable, and enjoyable because we love what we do, and we take pride in it.

It’s a lot of work.

Some writers are better than others, not unlike those crafters who work with wood. A good author is like a carpenter who makes a piece of furniture that will be handed down for generations.

Today seems a good day to revisit an article from February of 2020 on this very subject. Nothing has changed since I wrote this article, so here it is, a rerun that I hope you enjoy.

People often say they want to write a book. I used to say that too.

People often say they want to write a book. I used to say that too.

In 1985 I came across my first stumbling block on my path to becoming a writer. I didn’t know it, but to go from dreamer to storyteller is easy. Anyone can do it.

But if we choose to become an author, we’re taking a walk through an unknown landscape.

And the place where we go from dreamer to storyteller to author is the hardest part.

At first the path is gentle and easy to walk. As children, we invent stories and tell them to ourselves. As adults, we daydream about the stories we want to read, and we tell them to ourselves.

That part of the walk is easy. At some point, we become brave enough to sit down and put the story on paper.

The blank screen or paper is like an empty pond. All we have to do is add words, and the story will tell itself.

The first impedance that would-be authors come to on their way to filling the word-pond with words is a wide, deep river. It’s running high and fast with a flood of “what ifs” and partially visualized ideas.

If you truly want to become a writer, you must cross this river. If you don’t, the path ends here. While this river flows into the word-pond, the real path that takes us to a finished story is on the other side of this stream.

Fortunately, the river has several widely spaced steppingstones. Landing squarely on each one requires effort and a leap of faith, but the determined writer can do it.

The last thing you do before you step off the bank and begin crossing that river is this: visualize what your story is about.

The first stone you must leap to is the most difficult to reach. It is the one most writers who remain only dreamers falter at:

- You must give yourself permission to write.

We have this perception that it is selfish to spend a portion of our free time writing. It is not self-indulgent. We all must earn a living because very few writers are able to live on their royalties. If writing is your true craft, you must carve the time around your day job to do it. All you need is one undisturbed hour a day.

The second stone is an easy leap:

- Become literate. Educate yourself.

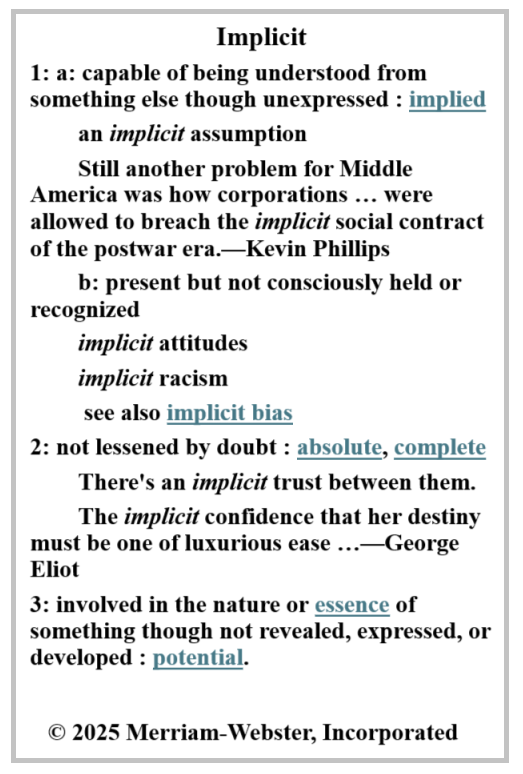

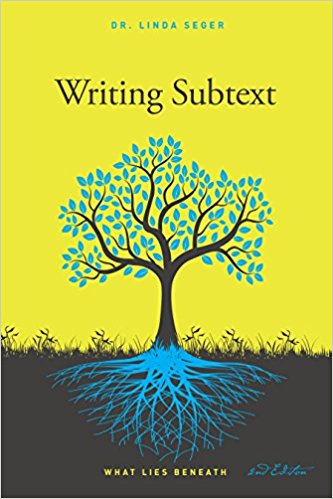

Buy books on the craft of writing. Buy and use the Chicago Manual of Style. You can usually find used copies on Amazon for around $10 – $15, passed on by those who couldn’t quite make the first leap.

I freely admit to using the internet for research, often on a daily basis, and I buy eBooks. However, my office bookshelves are filled with reference books on the craft of writing. I buy them as paper books because I am always looking things up. The Chicago Manual of Style is one of the most well-worn there.

Most professional editors rely on the CMOS because it’s the most comprehensive style guide—it has the answer for whatever your grammar question is. Best of all, it’s geared for writers of all streaks: essays, novels, all varieties of fiction, and nonfiction.

The third stone is the reason we decided to write in the first place:

- Good writers never stop reading for pleasure.

We begin as avid readers. A book resonates with us, makes us buy the whole series, and we never want to leave that world.

We soon learn that books like that are few and far between.

The fourth stone is an easy leap from that:

- We realize that we must write the book we want to read.

As we reach the far bank, we climb up and across the final hurdle:

- We finish the work, whether it’s a novel or short story.

Over the years since I first began writing, I’ve labored under many misconceptions. It was a shock to me when I discovered that we who write aren’t really special.

Over the years since I first began writing, I’ve labored under many misconceptions. It was a shock to me when I discovered that we who write aren’t really special.

Who knew?

We’re extremely common, as ordinary as programmers and software engineers. Everyone either wants to be a writer, is a writer, has a writer in the the family, or knows one.

Even my literary idols aren’t superhuman.

Because there are so many of us, it’s difficult to stand out. We must be highly professional, easy to work with, and literate.

Filling the pond with words and creating a story that hooks a reader is as easy as daydreaming and as difficult as giving birth.

Because writers are so numerous, every idea has been done. Popular tropes soon become stale and fall out of fashion.

A study by the University of Vermont says there are “six core trajectories which form the building blocks of complex narratives.” These are:

- Rags to riches (protagonist starts low and rises in happiness)

- Tragedy, or riches to rags (protagonist starts high and falls in happiness)

- Man in a hole (fall–rise)

- Icarus (rise–fall)

- Cinderella (rise–fall–rise)

- Oedipus” (fall–rise–fall)

No stale idea has ever been done your way.

No stale idea has ever been done your way.

We give that idea some thought. We apply a thick layer of our own brand of “what if.”

It’s our different approaches to these stories that make us each unique.

Sure, we’re writing an old story. But with a fresh angle, perseverance, and sheer hard work, we might be able to sell it.

And that is what makes the effort and agony of getting that book published and into the hands of prospective readers worthwhile.

Artist: John Williamson (1826–1885)

Artist: John Williamson (1826–1885)