Artist: Claude Lorrain (1604/1605–1682)

Artist: Claude Lorrain (1604/1605–1682)

Title: Seaport at sunset

Genre: landscape painting

Date: 1639

Medium: oil on canvas

Dimensions: height: 1 m (40.5 in); width: 1.3 m (53.9 in)

What I love about this painting:

Wow! Where to start? This is what true genius looks like. The overall scene is masterfully done, one of the best seascapes I have seen. The waters are calm, allowing for goods and passengers to be transferred safely to shore. The sky is that incredible quality that nature sometimes offers us on a summer evening. A haze is rising, and ships are still entering the harbor, waiting for their turn to offload their cargoes and passengers. Waves lap softly at the shore, a gentle rhythm.

Claude shows us a thriving, prosperous seaport under a glorious sunset. In fact, the scenery is so beautiful, it’s easy to overlook the dramas playing out in the foreground. However, we shouldn’t, as that is where the real story he wanted to show us lies.

In the bottom left, a family is seated on an upturned boat. Are they waiting to board a ship? They seem to be musicians, as the man plays a cittern, and a lute rests beside the woman and child, along with a pile of baggage.

To their right, a pair of merchants discuss business with a foreign trader, whose clothing suggests he is from Persia. Are they negotiating the purchase of rare spices? Or are they attempting to sell him something?

In the bottom center, violence has erupted as a pair of ruffians have decided to settle their dispute the old-fashioned way. Sailors on shore leave? Too much to drink? Fighting over a woman? The onlookers are disgusted but do not step in to break it up. Apparently, someone “had it coming.”

To the right of the combatants and knot of friends, a pair of well-dressed men, one seated on an upturned boat and one standing, are clearly waiting for something. Perhaps these people are all waiting to board the same ship.

And finally, on the far right, we have several ships, accompanied by small boats called tenders, which are going to and from them. In the foreground, sailors row tenders to the strand. Will our passengers be rowed out to board their ship? This is a bustling harbor, and it’s clear that berths along the quayside are at a premium. Perhaps, rather than paying for a berth when his cargo consists of passengers rather than goods, this ship’s owner keeps his costs down by bringing supplies on board by tender and ferrying passengers to and from the shore.

Claude’s glorious sunset hints that hope lies beyond the horizon. Are the passengers embarking on a journey to the New World? Perhaps they are going to India, or even to the French colonies in the South Pacific. Wherever they are going, I hope their journey is peaceful and ends well.

About the artist, via Wikipedia:

Claude Lorrain (born Claude Gellée), called le Lorrain in French; traditionally just Claude in English; c. 1600 – 23 November 1682) was a painter, draughtsman and etcher of the Baroque era originally from the Duchy of Lorraine. He spent most of his life in Italy, and is one of the earliest significant artists, aside from his contemporaries in Dutch Golden Age painting, to concentrate on landscape painting. His landscapes often transitioned into the more prestigious genre of history paintings by addition of a few small figures, typically representing a scene from the Bible or classical mythology. [1]

To learn more about this artist go to Claude Lorrain – Wikipedia

Credits and Attributions:

IMAGE: Seaport at sunset by Claude Lorrain 1682. Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:F0087 Louvre Gellee port au soleil couchant- INV4715 rwk.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:F0087_Louvre_Gellee_port_au_soleil_couchant-_INV4715_rwk.jpg&oldid=967103912 (accessed June 27, 2025).

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Claude Lorrain,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Claude_Lorrain&oldid=1298367934 (accessed July 2, 2025).

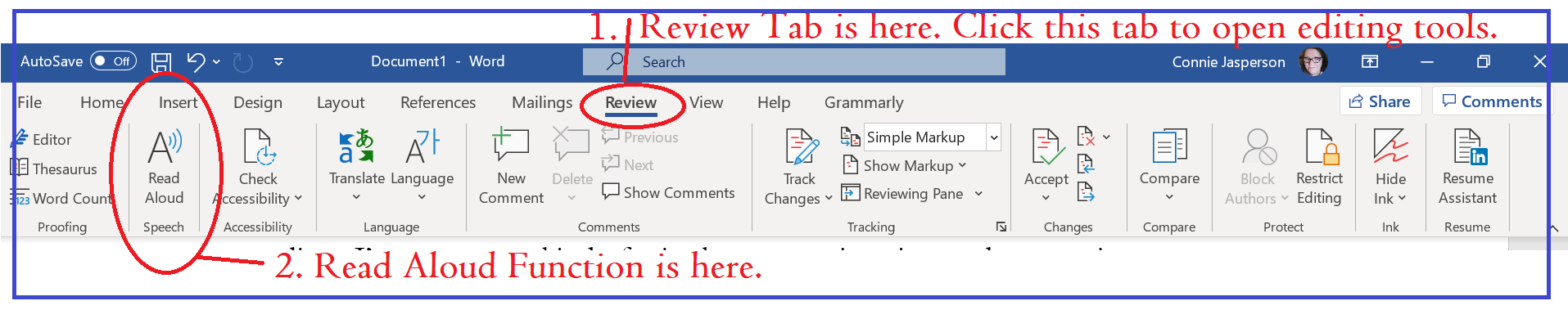

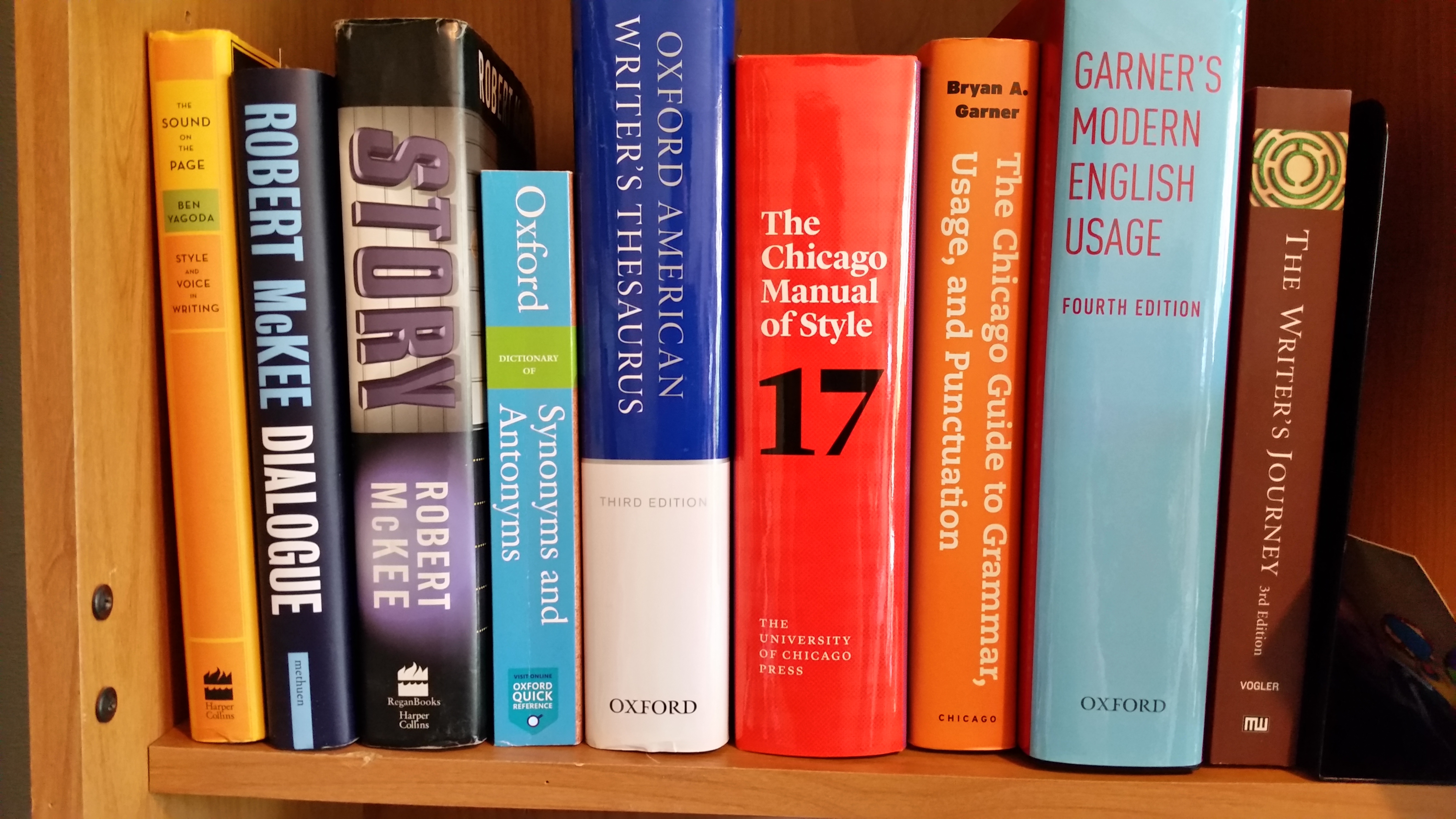

When prepping a novel to send to Irene, I use a three-part method. This requires specific tools that come with Microsoft Word, my word-processing program. I believe these tools are available for Google Docs and every other word-processing program. Unfortunately, I am only familiar with Microsoft’s products as they are what the companies that I worked for used.

When prepping a novel to send to Irene, I use a three-part method. This requires specific tools that come with Microsoft Word, my word-processing program. I believe these tools are available for Google Docs and every other word-processing program. Unfortunately, I am only familiar with Microsoft’s products as they are what the companies that I worked for used. Part two: Once I have ironed out the rough spots noticed by my beta readers, this second stage is put into action. Yes, on the surface the manuscript looks finished, but it has only just begun the journey.

Part two: Once I have ironed out the rough spots noticed by my beta readers, this second stage is put into action. Yes, on the surface the manuscript looks finished, but it has only just begun the journey. The most frustrating part is the continual stopping, making corrections, and starting.

The most frustrating part is the continual stopping, making corrections, and starting.

I am wary of relying on

I am wary of relying on  If you read as much as I do (and this includes books published by large Traditional publishers), you know that a few mistakes and typos can and will get through despite their careful editing. So, don’t agonize over what you might have missed. If you’re an indie, you can upload a corrected file.

If you read as much as I do (and this includes books published by large Traditional publishers), you know that a few mistakes and typos can and will get through despite their careful editing. So, don’t agonize over what you might have missed. If you’re an indie, you can upload a corrected file.