Many authors are just starting out in the craft and have never written anything longer than a memo or a social-media post before the novel they just finished. Once their manuscript is revised to their satisfaction, they might try to self-edit it rather than hire a freelance editor.

This can work if they took writing courses or had an education that included creative writing.

This can work if they took writing courses or had an education that included creative writing.

But I don’t recommend it. We see what we believe is there, not what is there.

A majority of new writers haven’t written since they left school. They don’t remember how to write a readable sentence or what a paragraph should (or should not) contain.

I certainly didn’t retain those skills. However, while I couldn’t afford to go back to college, I did go out of my way to educate myself.

First, we must think of punctuation as the traffic signal that keeps the words flowing and the intersections manageable.

Trying to learn from a grammar manual is daunting, to say the least. I learned by looking things up in the Chicago Manual of Style (CMoS), which is the rule book for American English, and from working with my editor. Most editors in the large traditional publishing houses refer to the CMoS when they have questions.

Trying to learn from a grammar manual is daunting, to say the least. I learned by looking things up in the Chicago Manual of Style (CMoS), which is the rule book for American English, and from working with my editor. Most editors in the large traditional publishing houses refer to the CMoS when they have questions.

I use Bryan A. Garner’s “the Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation.”

Maybe (like me) you came up in the world of business before the computer revolution. If so, you may be familiar with several other grammar style guides. Each is tailored to a particular kind of writing:

- The AP manual is for journalism.

- The Gregg manual for business writing.

- The CMoS is specifically for creative writing, such as fiction, memoirs, and personal essays, but also includes business and journalism rules.

You don’t need to know everything in the CMoS. If you know the fundamentals and are consistent with how you use them, your writing will pass most tests.

You don’t need to know everything in the CMoS. If you know the fundamentals and are consistent with how you use them, your writing will pass most tests.

Punctuation appears complicated when one is new to it. This confusion occurs because some advanced usages are open to interpretation. The way you habitually use them is your voice.

One thing remains clear: the foundational laws of comma use are not open to interpretation.

If you consistently follow seven simple rules, your work will look professional.

Rule one: commas and the fundamental rules for their use exist for a reason. If we want the reading public to understand our work, we need to follow them. Let’s get the “don’ts” out of the way:

- DO NOT insert commas “where you take a breath” because that many commas are unnecessary, and the habit creates run-on sentences.

- DO NOT insert commas where you think a sentence should pause because every reader sees the pauses differently.

Rule two: Commas can join two independent but related clauses with the aid of a conjunction. (I repeat: independent but related with the help of a conjunction.)

The independent clause is a complete standalone sentence.

- Boris worships the ground I walk on. His adoration tires me. (Two sentences.)

- Boris worships the ground I walk on, but his adoration tires me. (One sentence.)

Dependent clauses are unfinished and can’t stand on their own. Join them in the sentence with a conjunction and omit the comma this way:

- Boris worships the ground I walk on and brings me margaritas by the pool. (And is a conjunction, a joining word.)

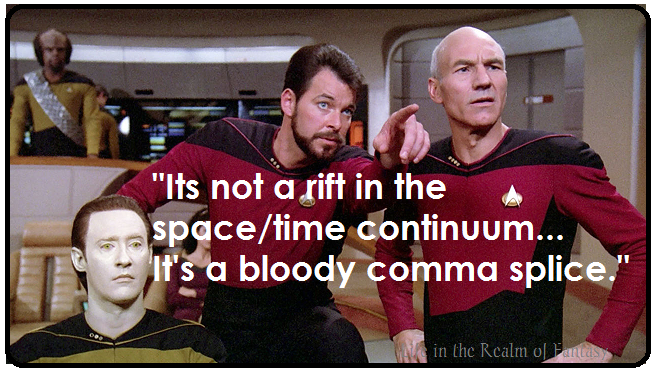

You do not join unrelated independent clauses (clauses that can stand alone as separate sentences) with commas as that creates a rift in the space/time continuum: the Comma Splice.

You do not join unrelated independent clauses (clauses that can stand alone as separate sentences) with commas as that creates a rift in the space/time continuum: the Comma Splice.

- Boris kissed the hem of my garment, Woofer, my dog, likes to ride shotgun.

What we have there is a wandering, run-on sentence created by the casual use of the comma splice. The dog has little to do with Boris other than the fact they both worship me. They should not be in the same paragraph, much less the same sentence. Here is the same thought, written correctly:

Boris kissed the hem of my garment.

Woofer, my dog, likes to ride shotgun.

- The dog riding shotgun is an independent clause and does not relate at all to Boris and his adoration of me. It is a different idea and should be in a separate paragraph. If you want Boris and the dog in the same sentence, you must rewrite it:

Boris and Woofer worship me and fight for the right to ride shotgun.

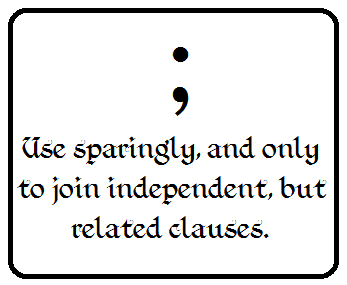

Rule three: a semicolon in an untrained hand is a dangerous thing. Some people (including Microsoft Word) think a semicolon signifies an extra-long pause but not a hard ending. The Chicago Manual of Style says that belief is wrong. Don’t blindly accept what Spellcheck or the AI editor app tells you!

Rule three: a semicolon in an untrained hand is a dangerous thing. Some people (including Microsoft Word) think a semicolon signifies an extra-long pause but not a hard ending. The Chicago Manual of Style says that belief is wrong. Don’t blindly accept what Spellcheck or the AI editor app tells you!

So, when do we use them? We only use them when two clauses are short, complete sentences that relate to each other. Here are two brief sentences that would be too choppy if left separate.

- The door swung open at a touch. Light spilled into the room. (2 related short standalone sentences.)

- The door swung open at a touch; light spilled into the room. (2 related short sentences joined by a semicolon.)

- The door swung open at a touch, and light spilled into the room. (1 compound sentence made from 2 related standalone clauses joined by a comma and a conjunction.) (A connector word.)

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

I don’t hate semicolons, although some editors do. However, I generally look for alternatives to them.

Rule four: Colons. These tidbits of punctuation commonly head lists found in technical writing. Colons are rarely needed in narrative prose. In technical writing, you might say something like:

For the next step, you will need:

- four nails,

- two feet of rope,

- one banana, whole and unpeeled.

I have no idea what they are building, but I can’t wait to see it.

Rule five: Oxford commas, also known as serial commas. This is the one war authors will never win or find common ground, a true civil war.

Rule five: Oxford commas, also known as serial commas. This is the one war authors will never win or find common ground, a true civil war.

When listing a string of things in a narrative, we separate them with commas to prevent confusion. I like people to understand what I mean, so I always use the Oxford Comma/Serial Comma.

If there are only two things in a list, they do not need to be separated by a comma. If there are more than two items, separate them with a comma.

We sell dogs, cats, rabbits, and birds.

Why do we need clarity? You might know what you mean, but not everyone thinks the same way.

- I accept this award and thank my late parents, Tad Williams and Poseidon.

That sentence might make sense to some readers, but not all. The intention of it is to thank my late parents, my favorite author, and the god of the sea. If I don’t thank Poseidon, my next fishing trip could end badly.

- I accept this award and thank my late parents, Tad Williams, and Poseidon.

Regardless of which stance you take on the Oxford/serial comma, choose your poison and be consistent.

Rule six: We use commas after introductory clauses.

After dark, Boris changes into his bat form and goes hunting for enchiladas.

Rule seven: When writing dialogue, all punctuation goes inside the quotation marks.

Rule seven: When writing dialogue, all punctuation goes inside the quotation marks.

- A comma follows the spoken words, separating the dialogue from the speech tag.

- The clause containing the dialogue is enclosed, punctuation and all, within quotes.

- The speech tag is the second half of the sentence, and a period ends the entire sentence.

The editor said, “I agree with those statements.”

- When dialogue is split by the speech tag, do not capitalize the first word in the second half.

“I agree with those statements,” said the editor, “but I wish you’d stop repeating yourself.”

If you follow these seven simple rules, your work will be readable. If your story is as original as you think it is, it will be acceptable to acquisitions editors.

Next week, we will continue our look at effective self-editing.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them. If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in  Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice. Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.