Many authors are just starting out and have never written anything longer than a memo or a tweet. Once that first manuscript is finished, they will self-edit it. But what if they didn’t have the luxury of a college education in journalism? Many new writers don’t know how to write a readable sentence or what constitutes a paragraph.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them.

Most public schools in the US no longer teach creative writing. While some do have some writing classes, the majority of students leave school with a minimal understanding of basic grammar mechanics.

- They know when they read something that is poorly written, but they don’t know what grammar error makes it wrong. It just feels awkward, so they stop reading.

We who love to read know good writing when we read it. We might have the idea for the best story and the dedication and desire to write it.

However, getting our thoughts onto paper so other readers can enjoy it is not our best skill—yet.

But it soon will be. First, we must think of punctuation as the traffic signal that keeps the words flowing and the intersections manageable.

Trying to learn from a grammar manual can be complicated. I learned by reading the Chicago Manual of Style, which is the rule book for American English. Most editors in the large traditional publishing houses refer to this book when they have questions.

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in Bryan A. Garner’s Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation. This is a resource with all the answers to questions about grammar and sentence structure. It takes the Chicago Manual of Style and boils it down to just the grammar.

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in Bryan A. Garner’s Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation. This is a resource with all the answers to questions about grammar and sentence structure. It takes the Chicago Manual of Style and boils it down to just the grammar.

There are other style guides, each of which is tailored to a particular kind of writing, such as the AP manual for journalism and the Gregg manual for business writing. The CMoS is specifically for creative writing, such as fiction, memoirs, and personal essays, but also includes business and journalism rules.

However, the basic rules are simple.

Punctuation seems complicated because some advanced usages are open to interpretation. In those cases, how you habitually use them is your voice. Nevertheless, the foundational laws of comma use are not open to interpretation.

Consistently follow these rules, and your work will look professional.

First, commas and the fundamental rules for their use exist for a reason. If we want the reading public to understand our work, we need to follow them.

Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

- Never insert commas “where you take a breath” because everyone breathes differently.

- Do not insert commas where you think it should pause because every reader sees the pauses differently.

Second: How do we use commas and coordinating conjunctions?

A comma should be used before these conjunctions: and, but, for, nor, yet, or, and so to separate two independent clauses. They are called coordinating conjunctions because they join two elements of equal importance.

However, we don’t always automatically use a comma before the word “and.” This is where it gets confusing.

Compound sentences combine two separate ideas (clauses) into one compact package. A comma should be placed before a conjunction only if it is at the beginning of an independent clause. So, use the comma before the conjunction (and, but, or) if the clauses are standalone sentences. If one of them is not a standalone sentence, it is a dependent clause, and you do not add the comma.

Take these two sentences: She is a great basketball player. She prefers swimming.

- If we combine them this way, we add a comma: She is a great basketball player, but she prefers swimming.

- If we combine them this way, we don’t: She is a great basketball player but prefers swimming.

The omission of one pronoun makes the difference.

You do not join unrelated independent clauses (clauses that can stand alone as separate sentences) with commas as that creates a rift in the space/time continuum: the Dreaded Comma Splice.

Boris kissed the hem of my garment, the dog likes to ride shotgun.

The dog has little to do with Boris other than the fact they both worship me. The same thought, written correctly:

Boris kissed the hem of my garment.

The dog likes to ride shotgun.

The dog riding shotgun is an independent clause and does not relate at all to Boris and his adoration of me. It should be in a separate paragraph. If you want Boris and the dog in the same sentence, you must rewrite it:

Boris and the dog worship me, and both like to ride shotgun.

Third, a semicolon in an untrained hand is a needle to the eye of the reader. Use them only when two standalone sentences or clauses are short and relate directly to each other.

Some people (including Microsoft Word) think a semicolon signifies an extra-long pause but not a hard ending. The Chicago Manual of Style and Bryan A Garner say that belief is wrong. Don’t blindly accept what Spellcheck tells you!

Semicolons join short independent clauses that can stand alone but which relate to each other. When do we use semicolons? Only when two clauses are short and are complete sentences that relate to each other. Here are two brief sentences that would be too choppy if left separate.

-

The door swung open at a touch. Light spilled into the room. (2 related short standalone sentences.)

-

The door swung open at a touch; light spilled into the room. (2 related short sentences joined by a semicolon.)

-

The door swung open at a touch, and light spilled into the room. (1 compound sentence made from 2 related standalone clauses joined by a comma and a conjunction.) (A connector word.)

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

I generally try to find alternatives to semicolons. they’re too easily abused because Microsoft Word and most people don’t know how to use them.

Fourth: Colons. These head lists but are more appropriate for technical writing. Colons are rarely needed in narrative prose. In technical writing, you might say something like:

For the next step, you will need:

- four bolts,

- two nail files,

- one peach, whole and unpeeled.

Technically speaking, I have no idea what they are building, but I can’t wait to see it!

Fifth: Oxford commas, also known as serial commas. This is the one war authors will never win or find common ground, a true civil war.

When listing a string of things in a narrative, we separate them with commas to prevent confusion. I like people to understand what I mean, so I always use the Oxford Comma/Serial Comma.

If there are only two things (or ideas) in a list, they do not need to be separated by a comma. If there are more than two ideas, the comma should be used as it would be used in a list.

We sell dogs, cats, rabbits, and picnic tables.

Why do we need clarity? You might know what you mean, but not everyone thinks the same way.

I accept this Nebula award and thank my late parents Irene Luvaul and Poseidon.

That sentence might make sense to some readers, but not in the way I intended. The intention of it is to thank my late parents, my editor, and the God of the Sea. If I don’t thank Poseidon, he’ll pitch a fit.

I accept this Nebula award and thank my late parents, Bob and Marge, my editor Irene Luvaul, and Poseidon, the God of the Sea.

Sixth: We use a comma after common introductory clauses.

After dark, Boris would change into his bat form and go hunting for enchiladas.

Seventh: Punctuating dialogue: All punctuation goes inside the quote marks.

- A comma follows the spoken words, separating the dialogue from the speech tag.

- The clause containing the dialogue is enclosed, punctuation and all, within quotes.

- The speech tag is the second half of the sentence, and a period ends the entire sentence.

The editor said, “I agree with those statements.”

If the dialogue is split by the speech tag, do not capitalize the first word in the second half.

“I agree with those statements,” said the editor, “but I wish you’d stop repeating yourself.”

Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

If you follow these seven simple rules, your work will be readable. If your story is creative and well-written, it will be acceptable to acquisitions editors.

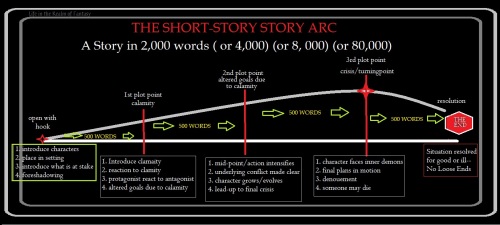

So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like

So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like  The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it?

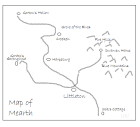

The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it? Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen.

Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen. Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

One of my favorite authors writes great storylines and creates wonderful characters. Unfortunately, the quality of his work has deteriorated over the last decade. It’s clear that he has succumbed to the pressure from his publisher, as he is putting out four or more books a year.

One of my favorite authors writes great storylines and creates wonderful characters. Unfortunately, the quality of his work has deteriorated over the last decade. It’s clear that he has succumbed to the pressure from his publisher, as he is putting out four or more books a year. This frequently happens to me in a first draft, but whoever is editing for him is letting it slide, as it pads the word count, making his books novel-length. I suspect they don’t have time to do any significant revisions.

This frequently happens to me in a first draft, but whoever is editing for him is letting it slide, as it pads the word count, making his books novel-length. I suspect they don’t have time to do any significant revisions. When we lay down the first draft, the story emerges from our imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard). Even with an outline, the story forms in our heads as we write it. While we think it is perfect as is, it probably isn’t.

When we lay down the first draft, the story emerges from our imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard). Even with an outline, the story forms in our heads as we write it. While we think it is perfect as is, it probably isn’t. Inadvertent repetition causes the story arc to dip. It takes us backward rather than forward. In my work, I have discovered that the second version of that idea is usually better than the first.

Inadvertent repetition causes the story arc to dip. It takes us backward rather than forward. In my work, I have discovered that the second version of that idea is usually better than the first. Here are a few things that stand out when I do this:

Here are a few things that stand out when I do this: If you have the resource of a good writing group, you are a bit ahead of the game. I suggest you run each revised chapter by your group and listen to what they say. Some of what you hear won’t be useful, but much will be.

If you have the resource of a good writing group, you are a bit ahead of the game. I suggest you run each revised chapter by your group and listen to what they say. Some of what you hear won’t be useful, but much will be. The publishing world is a rough playground. Editors for traditional publishing companies and small presses have a landslide of work to pick from and are chronically short-staffed. They can’t accept unprofessional work regardless of how good the story is.

The publishing world is a rough playground. Editors for traditional publishing companies and small presses have a landslide of work to pick from and are chronically short-staffed. They can’t accept unprofessional work regardless of how good the story is. Before you hire an editor, check their qualifications and references.

Before you hire an editor, check their qualifications and references.

If you’re a member of a writers’ group, you have a resource of people who will beta read for you at no cost. As a critique group member, you will read for them too.

If you’re a member of a writers’ group, you have a resource of people who will beta read for you at no cost. As a critique group member, you will read for them too. Clearly and consistently label each chapter. Ensure the chapter numbers are in the proper sequence, and don’t skip a number. I would label my individual chapter files this way:

Clearly and consistently label each chapter. Ensure the chapter numbers are in the proper sequence, and don’t skip a number. I would label my individual chapter files this way: If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in

I understand that slight incompatibility has been resolved. In my opinion, both programs are good, and both have pros and cons.

I understand that slight incompatibility has been resolved. In my opinion, both programs are good, and both have pros and cons. Most word processing programs have some form of spellcheck and some minor editing assists. Spellcheck is notorious for both helping and hindering you.

Most word processing programs have some form of spellcheck and some minor editing assists. Spellcheck is notorious for both helping and hindering you. You might disagree with the program’s suggestions. You, the author, have control and can disregard suggested changes if they make no sense. I regularly reject weird suggestions.

You might disagree with the program’s suggestions. You, the author, have control and can disregard suggested changes if they make no sense. I regularly reject weird suggestions. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess.

I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess. Also, it never hurts to have a book of synonyms on hand. We all tend to inadvertently repeat ourselves, and the Read Aloud function will shed light on those crutch words. A dictionary of synonyms and antonyms can help us find good alternatives.

Also, it never hurts to have a book of synonyms on hand. We all tend to inadvertently repeat ourselves, and the Read Aloud function will shed light on those crutch words. A dictionary of synonyms and antonyms can help us find good alternatives.

In some ways, novels are machines. Internally, each book is comprised of many essential components. If one element fails, the story won’t work the way I envision it.

In some ways, novels are machines. Internally, each book is comprised of many essential components. If one element fails, the story won’t work the way I envision it. So, realizing I knew nothing was the first positive thing I did for myself. I made it my business to learn all I could, even though I will never achieve perfection.

So, realizing I knew nothing was the first positive thing I did for myself. I made it my business to learn all I could, even though I will never achieve perfection. I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is.

I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is. This is the phase where I look for info dumps, passive phrasing, and timid words. These telling passages are codes for the author, laid down in the first draft. They are signs that a section needs rewriting to make it visual rather than telling. Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals telling me what I intend that scene to be. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination.

This is the phase where I look for info dumps, passive phrasing, and timid words. These telling passages are codes for the author, laid down in the first draft. They are signs that a section needs rewriting to make it visual rather than telling. Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals telling me what I intend that scene to be. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination. Editing programs operate on algorithms and don’t understand context. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess.

Editing programs operate on algorithms and don’t understand context. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess. I do use Grammarly—but also, I don’t.

I do use Grammarly—but also, I don’t. Spellcheck doesn’t understand context, so if a word is misused but spelled correctly, it may not alert you to an obvious error.

Spellcheck doesn’t understand context, so if a word is misused but spelled correctly, it may not alert you to an obvious error. Even editors must have their work seen by other eyes. My blog posts are proof of this as I am the only one who sees them before they are posted. Even though I write them in advance, go over them with two editing programs, and then look at them again before each post goes live, I still find silly errors two or three days later.

Even editors must have their work seen by other eyes. My blog posts are proof of this as I am the only one who sees them before they are posted. Even though I write them in advance, go over them with two editing programs, and then look at them again before each post goes live, I still find silly errors two or three days later. Prose, plot, transitions, pacing, theme, characterization, dialogue, and mechanics (grammar/punctuation).

Prose, plot, transitions, pacing, theme, characterization, dialogue, and mechanics (grammar/punctuation). I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is.

I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is. This phase is where I find my punctuation errors most often. I look for and correct punctuation and make notes for any other improvements that must be made. Usually, I cut entire sections, as they are riffs on ideas that have been presented before. Sometimes they are outright repetitions, which don’t leap out when viewed on the computer screen.

This phase is where I find my punctuation errors most often. I look for and correct punctuation and make notes for any other improvements that must be made. Usually, I cut entire sections, as they are riffs on ideas that have been presented before. Sometimes they are outright repetitions, which don’t leap out when viewed on the computer screen. Passive phrasing does the job with little effort on the part of the author, which is why the first drafts of my work are littered with it. Active phrasing takes more effort because it involves visualizing a scene and showing it to the reader.

Passive phrasing does the job with little effort on the part of the author, which is why the first drafts of my work are littered with it. Active phrasing takes more effort because it involves visualizing a scene and showing it to the reader.