Many new authors use the word mood interchangeably with atmosphere when describing a scene or passage. This is because mood and atmosphere are like conjoined twins. They are individuals but are difficult to separate as they share some critical functions. This is the layer of worldbuilding that lies just below the surface, a component of the inferential layer of the narrative.

Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood shapes (and is shaped by) the emotions evoked within the story.

Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood shapes (and is shaped by) the emotions evoked within the story.

Atmosphere is also long-term but is sometimes more noticeable as it is a component of worldbuilding. Atmosphere is the aspect of mood that is conveyed by the setting.

Emotion is immediate and short-term and is also subtle and lurking in the background. The characters feelings affect the reader’s experience of the overall atmosphere and mood.

Robert McKee tells us that emotion is the experience of transition, of the characters moving between a state of positivity and negativity. “Story” by Robert McKee. Emotions are fluid, generating energy, and give life to the narrative.

Robert McKee tells us that emotion is the experience of transition, of the characters moving between a state of positivity and negativity. “Story” by Robert McKee. Emotions are fluid, generating energy, and give life to the narrative.

I look for books where the author shows emotions in a way that feels dynamic. Our characters are in a state of flux, and their emotional state should also be. When the character’s internal struggle is turbulent, ranging from positive to negative and back, their story becomes personal to me.

Mood is a significant word serving several purposes. It is created by the setting (atmosphere), the exchanges of dialogue (conversation), and the tone of the narrative (word choices, descriptions). It is also affected by (and refers to) the emotional state of the characters—their personal mood.

Undermotivated emotions lack credibility and leave the reader feeling as if the story is flat. In real life, we have deep, personal reasons for our feelings, and so must our characters.

A woman shoots another woman. Why? What emerges as the story progresses is that a road accident occurred three years before in which her child was accidentally struck and killed by the woman she murdered.

My worldbuilding for that story should convey an atmosphere of shadows, sort of like a “film noir.” Everything my characters see and interact with should be symbolic, conveying a range of dark emotions in the opening pages in which the gun is fired, and the woman falls dead. If I do it right, I’ll have intense emotion and high drama.

In real life, people have reasons for their actions, irrational though they may be. The root cause of a person’s emotional state drives their actions. In the case of the above story, the driving force is a descent into a mad desire to avenge what was an unintentional tragedy. Every aspect of the setting should reflect that intense anger, the deep-rooted hatred, and the unfairness of it all.

These visuals can easily be shown. Grief manifests in many ways and can become a thread running through the entire narrative. That theme of intense, subliminal emotion is the underlying mood and it shapes the story:

These visuals can easily be shown. Grief manifests in many ways and can become a thread running through the entire narrative. That theme of intense, subliminal emotion is the underlying mood and it shapes the story:

- Many people are affected by the murder, family members on both sides, and also the law enforcement officers who must investigate it.

How can we show it? We use worldbuilding to create an atmosphere of gloom. Outside each window, whenever a character must leave their home or office, the days are dark, damp, and chill. The lack of sunshine and the constant rain wears on all the characters involved on either side of the law.

- The setting underscores each of the main characters’ personal problems and evokes a general sense of loss and devastation.

Which is more important, mood or emotion? Both and neither. Characters’ emotions affect their attitudes, which in turn shape the overall mood of a story. In turn, the atmosphere of a particular environment may affect the characters’ personal mood. Their individual attitudes affect the emotional state of the group.

As we have said before, emotion is the experience of transition from the negative to the positive and back again. Each evolution of the characters’ emotions shapes their conscious beliefs and values. They will either grow or stagnate.

This is part of the inferential layer, as the audience must infer (deduce) the experience. You can’t tell a reader how to feel. They must experience and understand (infer) what drives the character on a human level.

This is part of the inferential layer, as the audience must infer (deduce) the experience. You can’t tell a reader how to feel. They must experience and understand (infer) what drives the character on a human level.

What is mood in literature? Wikipedia says mood is established in order to affect the reader emotionally and psychologically and to provide a feeling of experience for the narrative.

What is atmosphere? It is worldbuilding, created by the words we choose. We can feel it, but it is intangible. But atmosphere affects how the reader perceives the story. The way a setting is described contributes to the atmosphere, and that description is a component of worldbuilding.

Atmosphere is the result of deliberate word choices. It comes into play when we place certain visual elements into the scenery with the intention of creating an emotion in the reader.

- Tumbleweeds rolling across a barren desert.

- Waves crashing against cliffs.

- Dirty dishes resting beside the sink.

- A chill breeze wafting through a broken window.

We show these conjoined twins of mood and atmosphere through subtle clues: odors, ambient sounds, and the surrounding environment. They are intensified by the characters’ attitudes and emotions. Mood and atmosphere are organic components of the environment but are also an intentional ambiance.

As we read, the atmosphere that is shown within the pages colors and intensifies our emotions, and at that point, they feel organic. Think about a genuinely gothic tale: the mood and atmosphere Emily Brontë instilled into the setting of Wuthering Heights make the depictions of mental and physical cruelty seem like they would happen there.

As we read, the atmosphere that is shown within the pages colors and intensifies our emotions, and at that point, they feel organic. Think about a genuinely gothic tale: the mood and atmosphere Emily Brontë instilled into the setting of Wuthering Heights make the depictions of mental and physical cruelty seem like they would happen there.

Happy, sad, neutral—atmosphere and mood combine to intensify or dampen the emotions our characters experience. They underscore the characters’ struggles.

For me, as a writer, conveying the inferential layer of a story is complicated. Creating a world on paper requires thought even when we live in that world. We know how the atmosphere and mood of our neighborhood feels when we walk to the store. But try conveying that mood and atmosphere in a letter to a friend – it’s more complicated than it looks.

Showing what is going on inside our characters’ heads is tricky. We will go a little deeper into that next week.

However, there is an accessible viewpoint just at the entrance, and we can go there and just absorb the peace. Several years ago, I shot this photo from that platform.

However, there is an accessible viewpoint just at the entrance, and we can go there and just absorb the peace. Several years ago, I shot this photo from that platform.

Action and interaction – we know how the surface of a pond is affected by the breeze that stirs it. In the case of our novel, the breeze that stirs things up is made of motion and emotion. These two elements shape and affect the structural events that form the plot arc.

Action and interaction – we know how the surface of a pond is affected by the breeze that stirs it. In the case of our novel, the breeze that stirs things up is made of motion and emotion. These two elements shape and affect the structural events that form the plot arc. So, how can we use the surface elements to convey a message or to poke fun at a social norm? In other words, how can we get our books banned in some parts of this fractured world?

So, how can we use the surface elements to convey a message or to poke fun at a social norm? In other words, how can we get our books banned in some parts of this fractured world? Creating depth in our story requires thought and rewriting. The first draft of our novel gives us the surface, the world that is the backdrop.

Creating depth in our story requires thought and rewriting. The first draft of our novel gives us the surface, the world that is the backdrop.

If I were writing a story starring me as the main character, I would open it in the year 2005 with a couple of empty-nesters buying a house in a bedroom community twenty miles south of Olympia.

If I were writing a story starring me as the main character, I would open it in the year 2005 with a couple of empty-nesters buying a house in a bedroom community twenty miles south of Olympia. The city center is isolated, twelve miles from the freeway and twenty miles away from every other town in the south county. If a fictional story were set in this town, it would feature the same political and religious schisms that divide the rest of our country. There are other tensions. Some families have been here for generations, and a few don’t appreciate the influx of low-paid state workers buying cookie-cutter tract homes (like mine) here.

The city center is isolated, twelve miles from the freeway and twenty miles away from every other town in the south county. If a fictional story were set in this town, it would feature the same political and religious schisms that divide the rest of our country. There are other tensions. Some families have been here for generations, and a few don’t appreciate the influx of low-paid state workers buying cookie-cutter tract homes (like mine) here. Two inches of rain fell the day we moved into our brand-new home in 2005, making moving our furniture into this house a misery. Our new house had no landscaping and rose from a sea of mud and rocks. With a lot of effort, we made a pleasant yard. When the housing bubble burst in 2008, many people on my side of the street lost their jobs, and some homes went into foreclosure.

Two inches of rain fell the day we moved into our brand-new home in 2005, making moving our furniture into this house a misery. Our new house had no landscaping and rose from a sea of mud and rocks. With a lot of effort, we made a pleasant yard. When the housing bubble burst in 2008, many people on my side of the street lost their jobs, and some homes went into foreclosure. Our main street, Sussex, passes through a historic district. The buildings are all built from sandstone quarried at the old quarries. Many of the old buildings are home to antique stores. The masonic lodge is made of Tenino sandstone.

Our main street, Sussex, passes through a historic district. The buildings are all built from sandstone quarried at the old quarries. Many of the old buildings are home to antique stores. The masonic lodge is made of Tenino sandstone.

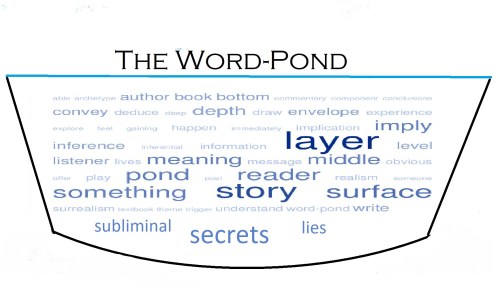

We know our story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. We sense something murky and mysterious in the middle. We instinctively know the pond is made up of layers, although we may not consciously be aware of it or be able to explain it.

We know our story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. We sense something murky and mysterious in the middle. We instinctively know the pond is made up of layers, although we may not consciously be aware of it or be able to explain it. Surrealism seeks to release the creative potential of the unconscious mind, for example, by the irrational juxtaposition of images—think

Surrealism seeks to release the creative potential of the unconscious mind, for example, by the irrational juxtaposition of images—think  All the characters have reasons for their actions. The author offers implications and lets the reader come to their own conclusions. The reader sees the hints, allegations, and inferences, and the underlying story of each character takes shape in their mind.

All the characters have reasons for their actions. The author offers implications and lets the reader come to their own conclusions. The reader sees the hints, allegations, and inferences, and the underlying story of each character takes shape in their mind. This layer will be shallower in Romance novels because the book’s point isn’t a more profound meaning—it’s interpersonal relationships on a surface level. However, there will still be some areas of mystery that aren’t spelled out entirely because the interpersonal intrigues are the story.

This layer will be shallower in Romance novels because the book’s point isn’t a more profound meaning—it’s interpersonal relationships on a surface level. However, there will still be some areas of mystery that aren’t spelled out entirely because the interpersonal intrigues are the story. This is the interpretive level:

This is the interpretive level:

![Herbert Gustave Schmalz [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/480px-schmalz_galahad.jpg?w=240&h=300)

![Charles Ernest Butler [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/charles_ernest_butler_-_king_arthur-via-wikimedia-commons.jpg?w=178&h=300)

![Judith Leyster [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/judith_leyster_the_proposition.jpg?w=238&h=300)

![Impression Sunrise, Claude Monet 1872 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/claude_monet_impression_soleil_levant.jpg?w=300&h=233)