Artist: Asher Brown Durand (1796–1886)

Artist: Asher Brown Durand (1796–1886)

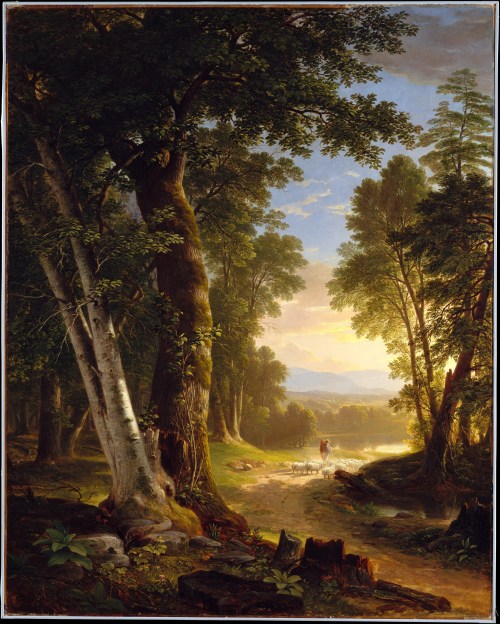

Title: The Beeches

Genre: landscape art

Date: 1845

Medium: oil on canvas

Dimensions: 60 3/8 x 48 1/8 in. (153.4 x 122.2 cm)

Collection: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Current location: American Paintings and Sculpture

What I love about this painting:

It’s been raining cats and dogs here, a regular monsoon. There has been some minor flooding here as the street drains aren’t able to cope with the quantities of rain that has fallen for the last week. It seems like a good time to revisit one of my favorite paintings, one detailing a sunny day painted during a calmer time.

Asher Brown Durand gives us a summer day on the shore of a large pond, in a grove of beech and birch trees. The large beech tree is magnificent, with its rough, moss-covered bark commanding the center stage. In the distance, as if they were accidentally included, a shepherd leads a flock of sheep, a minor part of the scene as compared to the superb majesty of the beech tree.

Yet, nothing in this painting is accidental. The sheep and their shepherd are painted in exquisite detail, with as much attention as he gives to the texture of the bark and the moss. Each leaf, each blade of grass, each stone—every part of this scene is painted with intention. Each component of this landscape painting is as true and perfect as they were in real life.

I love the natural feeling of the plants, the intense colors of nature, the sense of a place that is vibrant and alive.

This painting is not merely a photographic representation of a summer morning in 1845. It has a life, a sense that you are there. We can almost feel the warming sunshine and slight breeze lifting the morning haze, hear the sheep as they walk to the water, perhaps even catch the earthy scent of the woods around us.

What story will you find in this scene? I think there are several. The observer has a story, but so does the shepherd and the sheep. The tree also has a story, but trees rarely tell what they know.

Durand was a master in the Hudson River School, a group of artists who believed that nature in the form of the American landscape was a reflection of God. Durand himself wrote, “The true province of Landscape Art is the representation of the work of God in the visible creation.” [1]

This painting demonstrates that conviction.

About the Artist, via Wikipedia:

Asher Brown Durand (August 21, 1796, – September 17, 1886). (He) was an American painter of the Hudson River School. was born in, and eventually died in, Maplewood, New Jersey (then called Jefferson Village). He was the eighth of eleven children. Durand’s father was a watchmaker and a silversmith.

Durand was apprenticed to an engraver from 1812 to 1817 and later entered into a partnership with the owner of the company, Charles Cushing Wright (1796–1854), who asked him to manage the company’s New York office. He engraved Declaration of Independence for John Trumbull during 1823, which established Durand’s reputation as one of the country’s finest engravers. Durand helped organize the New York Drawing Association in 1825, which would become the National Academy of Design; he would serve the organization as president from 1845 to 1861.

Asher’s engravings on bank notes were used as the portraits for America’s first postage stamps, the 1847 series. Along with his brother Cyrus he also engraved some of the succeeding 1851 issues.

Durand’s main interest changed from engraving to oil painting about 1830 with the encouragement of his patron, Luman Reed. In 1837, he accompanied his friend Thomas Cole on a sketching expedition to Schroon Lake in the Adirondacks Mountains, and soon after he began to concentrate on landscape painting. He spent summers sketching in the Catskills, Adirondacks, and the White Mountains of New Hampshire, making hundreds of drawings and oil sketches that were later incorporated into finished academy pieces which helped to define the Hudson River School.

Durand is remembered particularly for his detailed portrayals of trees, rocks, and foliage. He was an advocate for drawing directly from nature with as much realism as possible. [1]

Credits and Attributions:

Image: The Beeches by Asher Brown Durand, PD|100. Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:The Beeches MET DT75.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:The_Beeches_MET_DT75.jpg&oldid=617658539 (accessed November 6, 2025).

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Asher Brown Durand,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Asher_Brown_Durand&oldid=1129313847 (accessed November 6, 2025).

Title: Indian Summer by William Trost Richards

Title: Indian Summer by William Trost Richards Artist:

Artist: Cider Pressing by George Henry Durrie 1855

Cider Pressing by George Henry Durrie 1855

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)![Albert Bierstadt [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/1875_bierstadt_albert_mount_adams_washington.jpg?w=500)

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)