The Buddha offered a morsel of wisdom that authors should consider, “There has to be evil so that good can prove its purity above it.”

J.R.R. Tolkien understood this quite clearly.

Written in a style that was popular one-hundred years ago, the Lord of the Rings trilogy is a large reading commitment, one fewer and fewer readers are willing to undertake. Yet, compared to Robert Jordan or Tad Williams’ epic fantasy series, it is short, totaling only 455,175 words over the course of three books.

Written in a style that was popular one-hundred years ago, the Lord of the Rings trilogy is a large reading commitment, one fewer and fewer readers are willing to undertake. Yet, compared to Robert Jordan or Tad Williams’ epic fantasy series, it is short, totaling only 455,175 words over the course of three books.

The story is sprawling, showing a world of plenty, ignorant of the disaster lurking at the edge of their border. Tolkien shows the peace and prosperity that Frodo enjoys and then forces him down a road not of his choosing. He takes the hobbit through personal changes, forces him to question everything. In the final confrontation with Sauron’s evil influence, Tolkien forces Frodo to face the fact he isn’t quite strong enough to destroy the ring. Frodo can’t give it up—he is willing to risk everything to retain possession of it when Gollum amputates his finger and takes the ring.

Frodo and Sam hunting down a case of genuine Canadian beer and spending spring break in Fort Lauderdale wouldn’t make much of a story, although it could have made an awesome straight-to-DVD movie.

Frodo’s story is about good and evil, and the hardships endured in the effort to destroy the One Ring and negate the power of Sauron. Why would ordinary middle-class people, comfortable in their rut, go to so much trouble if Sauron’s evil was no threat?

In both the Lord of the Rings trilogy and Tad Williams’ epic fantasy Osten Ard series, we have two of the most enduring works of modern fiction. Both feature an epic quest where through it all, we have joy and contentment sharply contrasted with deprivation and loss, drawing us in and inspiring the deepest emotions.

This use of contrast is fundamental to the fables and sagas humans have been telling since before discovering fire. Contrast is why Tolkien’s saga set in Middle Earth is the foundation upon which modern epic fantasy is built. It’s also why Tad Williams’ work in The Dragonbone Chair, first published in 1988, changed the way people saw the genre of epic fantasy, turning it into hard fantasy. The works of these authors inspired a generation of writers: George R.R. Martin and Patrick Rothfuss, to name just two of the more famous.

My favorite books convey the beauty of life by contrasting joy, companionship, and love with drama, heartache, and violence. No matter the setting, Paris or Middle Earth, these fundamental human experiences are personal to each reader. They have experienced pain and loss, joy and love. When the author does it right, the reader empathizes, feels the emotions written into the story as if they were the protagonist.

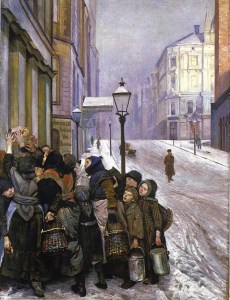

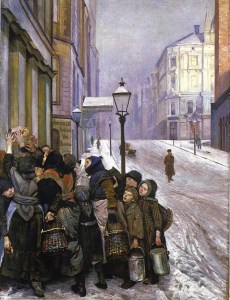

Hunger is a fundamental agony that can linger for years. People can survive on very little, and unfortunately, many do. To have only enough food to keep you alive, but never enough to allow you to grow and thrive forms a person in a singular way. Acquiring food becomes your first priority. Having a surplus of food becomes a reason to celebrate. To go without adequate food for any length of time changes you, makes you more determined than ever to never go hungry again.

Hunger is a fundamental agony that can linger for years. People can survive on very little, and unfortunately, many do. To have only enough food to keep you alive, but never enough to allow you to grow and thrive forms a person in a singular way. Acquiring food becomes your first priority. Having a surplus of food becomes a reason to celebrate. To go without adequate food for any length of time changes you, makes you more determined than ever to never go hungry again.

Thirst is a more immediate pain than hunger. The human animal can survive for up to three weeks without food, but only three to four days without water. Rarely, one can survive up to a week. When one has gone without water for any length of time, even brackish water must taste sweet. And when one is without food, even food they would never normally eat will fill their belly.

War happens because of famine and deprivation. Wars are fought over water. We forget this when we have plenty to eat and never worry if we will have water or not as long as we can pay the bills.

Need drives the human story, which is why we love tales of heroism and great achievements. Love and loss, safety and danger, loyalty and betrayal—contrast provides the story with texture, turning a bland wall of words into something worth reading. First comes the calm, and then the storm, and then the aftermath. Feast is followed by famine, thirst followed by a flood. War, famine, and flood are followed by a time of peace and plenty. This is our history, and our future, and is how good tales are played out.

Employing contrast gives texture to the fabric of a narrative. When an author makes good use of contrasts to draw the reader in, readers will think about the story and those characters long after it has ended.

I say this regularly, but I must repeat it: education about the craft of writing has many facets. We must learn the basics of grammar, and we must learn how to build a story. We learn the architecture of story by reading novels and short stories written by the masters, both famous and infamous.

I say this regularly, but I must repeat it: education about the craft of writing has many facets. We must learn the basics of grammar, and we must learn how to build a story. We learn the architecture of story by reading novels and short stories written by the masters, both famous and infamous.

We can’t limit our reading to the classics. Those books may be the basis for the way fiction is written today, but the prose and style don’t resonate with the majority of modern readers.

I have a piece of homework for you. You can copy and use the following list of questions as part of your assignment.

We may not love the novels on the NY Times bestseller list, and we may find them hard going, but stay with it. Go to the library or to the bookstore and see what they have from that list that you would be willing to examine. Your local second hand bookstore might have quite a few recent bestsellers in their stock of general fiction. Buy or borrow it and give it a postmortem. Why does—or doesn’t—the piece resonate with you? Why would a book that you dislike be so successful?

As I said at the beginning, the plot is driven by the events and emotions that give it texture. How did they unfold? Did the book have a distinct plot arc? Did it have:

-

A strong opening to hook you?

-

Was there originality in the way the characters and situations were presented?

-

Did you like the protagonist and other main characters? Why or why not?

-

Were you able to suspend your disbelief?

-

Did the narrative contain enough contrasts to keep things interesting?

-

By the end of the book, did the characters grow and change within their personal arc? How were they changed?

-

What sort of transitions did the author employ that made you want to turn the page? How can you use that kind of transition in your own work?

-

Did you get a satisfying ending? If not, how could it have been made better?

Reading and dissecting the works of successful authors is a necessary component of any education in the craft of writing. Answering these questions will make you think about your own work, and how you deploy the contrasting events that change the lives of your characters.

Credits and Attributions:

Struggle for Survival by Christian Krohg, 1889, oil on canvas. Now hanging in the National Gallery of Norway.

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Christian Krohg-Kampen for tilværelsen 1889.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Christian_Krohg-Kampen_for_tilv%C3%A6relsen_1889.jpg&oldid=301415583 (accessed February 10, 2019)

![Mourning Dove on Easter Day, by Kazvorpal [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/800px-mourning_dove_on_easter_day.jpg?w=225&h=300) Fluffy white clouds drift overhead, hummingbirds dart here and there, my eyes close, and I absorb the sounds of my small town all around me.

Fluffy white clouds drift overhead, hummingbirds dart here and there, my eyes close, and I absorb the sounds of my small town all around me.