Arcs of action drive plots. Every reader knows this, and every writer tries to incorporate that knowledge into their work. Unfortunately, when I’m tired, random, disconnected events that have no value will seem like good ideas. Action inserted for shock value can derail what might have been a good plot.

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning.

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning.

Nowadays, I avoid forcing my brain to work when it’s on its last legs. I no longer commit myself to a manuscript rife with random events inserted out of desperation. I brainstorm my ideas in a separate document and choose the ones that work best. So, in that regard, my writing style in the first stages is more like creating an extensive and detailed outline. This method allows me to be as creative as I want while I build an overall logic into the evolving story.

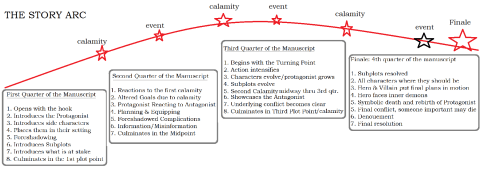

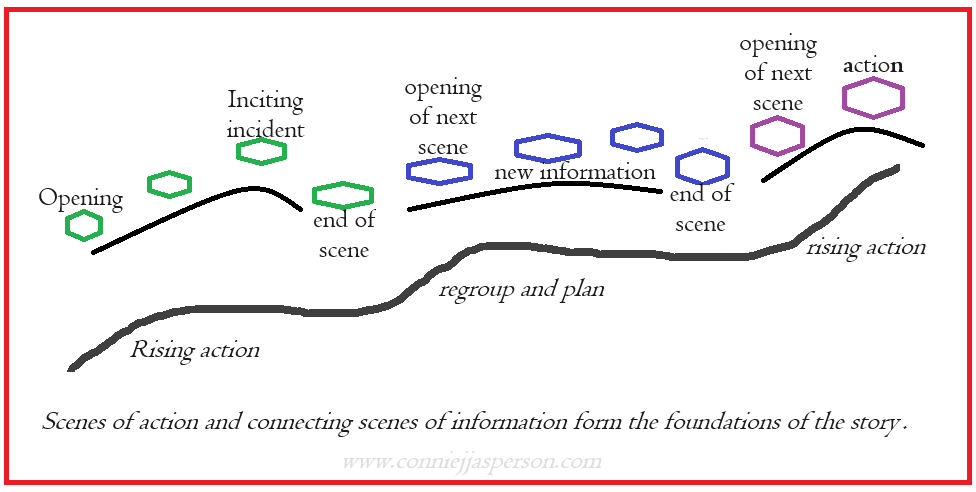

At the story’s outset, we meet our protagonist and see them in their familiar surroundings. The inciting incident occurs once we have met them, whether they are ready for it or not. At that point, we must take them to the next stumbling block. But what is that impediment, and how do we overcome it?

Answering that question isn’t always easy. The place where writing becomes work is a hurdle the majority of people who “always wanted to be an author” can’t leap. Their talents lie elsewhere.

I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending.

I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending.

Sometimes, it helps to write the last chapter first – in other words, start with the ending. That is how my first NaNoWriMo novel in 2010 began. I was able to pound out 68,000 words in 30 days because I had great characters, and I was desperate to uncover how they got to that place in their lives.

So, where are we in the story arc when the first lull in creativity occurs? Many times, it is in the first ten pages.

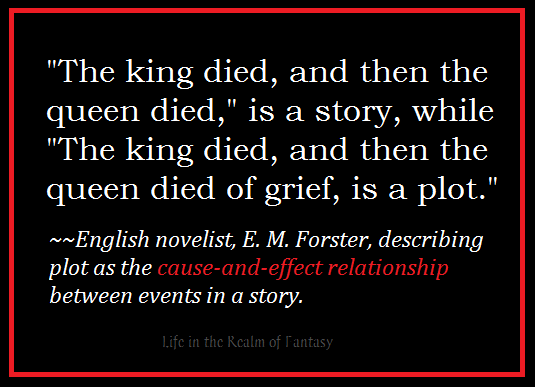

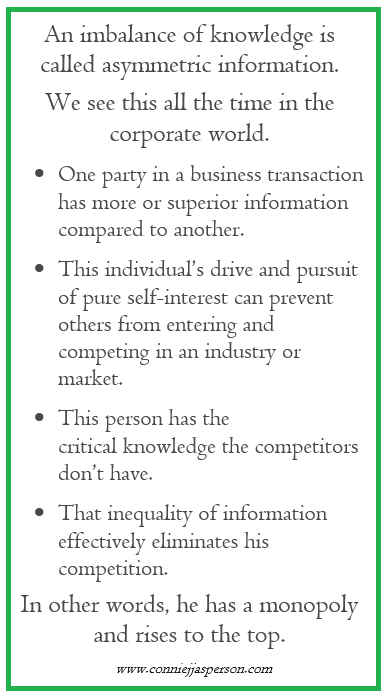

An imbalance of power drives plots. The dark corners of the story are illuminated by the characters who have critical knowledge. This is called asymmetric information, and the enemy should have more of that commodity than our protagonist.

The enemy puts their plan in motion, and we have action. The protagonists are moved to react. The characters must work with a limited understanding of the situation because asymmetric information creates tension. A lack of knowledge creates a crisis.

Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals.

Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals.

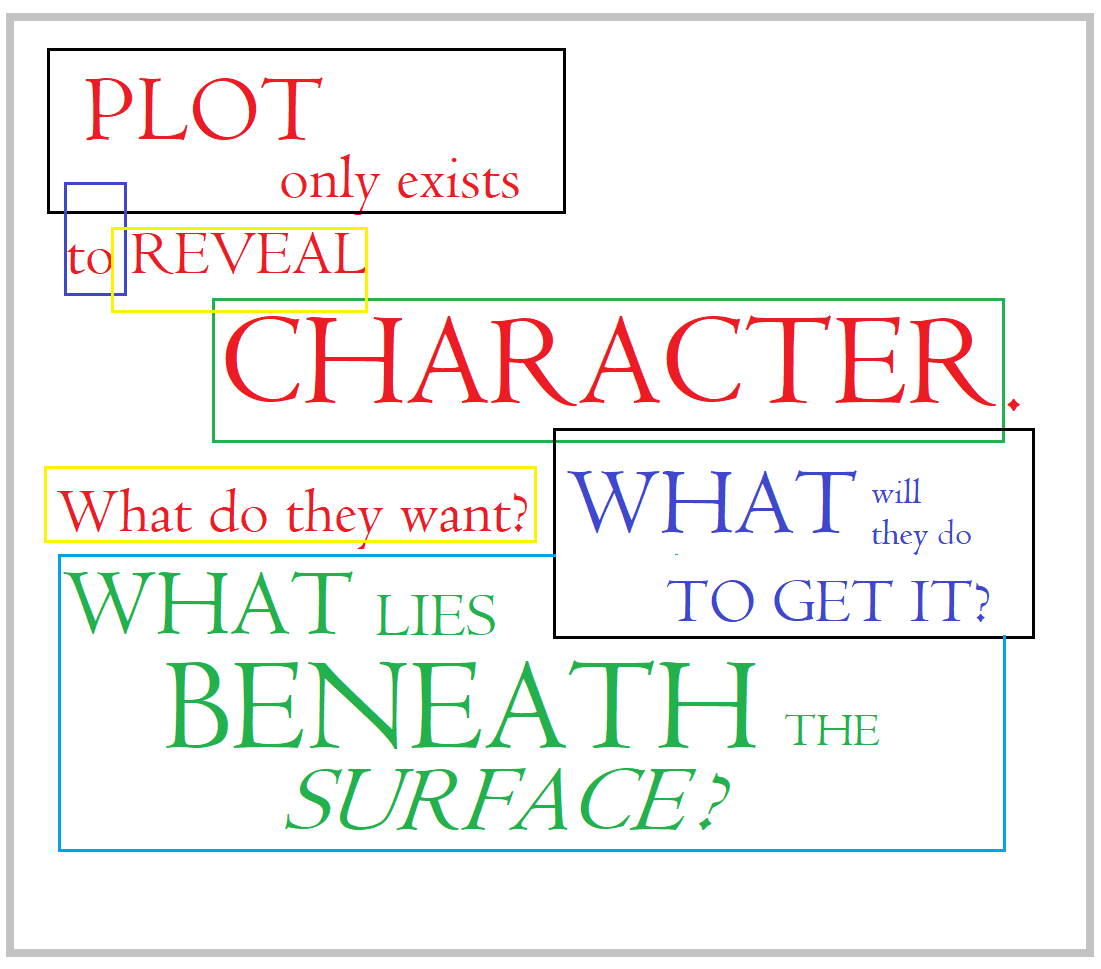

At several points in this process, I will stop and think about the characters. What do they want? How motivated are they to get it? If they aren’t motivated, why are they there?

Answering a few questions about your characters can kick the plot back into motion. Start with the antagonist because his actions force our characters to react:

- Why does the enemy have the upper hand?

- How does the protagonist react to pressure from the antagonist?

- How does the struggle affect the relationships between the protagonist and their cohorts/romantic interests?

- What complications arise from a lack of information?

- How will the characters acquire that necessary information?

Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

I lay down the skeleton of the tale, fleshing out what I can as I go. However, there are significant gaps in this early draft of the narrative.

So, once the first draft is finished, I flesh out the story with visuals and action. Those are things I can’t focus on in the first draft, but I do insert notes to myself, such as:

- Fend off the attack here.

- Shouldn’t they plan some sort of assault here? Or are they just going to defend forever? Make them do something!

- Contrast tranquil scenery with turbulent emotions here.

My first drafts are always rough, more like a series of events and conversations than a novel. I will stitch it all together in the second draft and fill in the plot holes.

At least, that is my intention, but it usually takes five or six drafts to make a coherent story with a complete plot arc and interesting characters with logical actions and reactions.

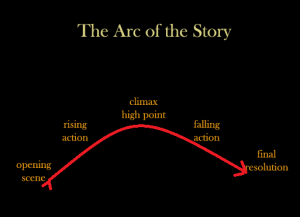

After we survive the middle crisis, we have falling action. We receive the crucial information, the characters regroup, and we experience the unfolding of events leading to the conclusion. The protagonist’s problems are resolved, and we (the readers) are offered a good ending and closure.

After we survive the middle crisis, we have falling action. We receive the crucial information, the characters regroup, and we experience the unfolding of events leading to the conclusion. The protagonist’s problems are resolved, and we (the readers) are offered a good ending and closure. These small arcs of action, reaction, and calm push the plot and ensure it doesn’t stall. Each scene is an opportunity to ratchet up the tension and increase the overall conflict that drives the story.

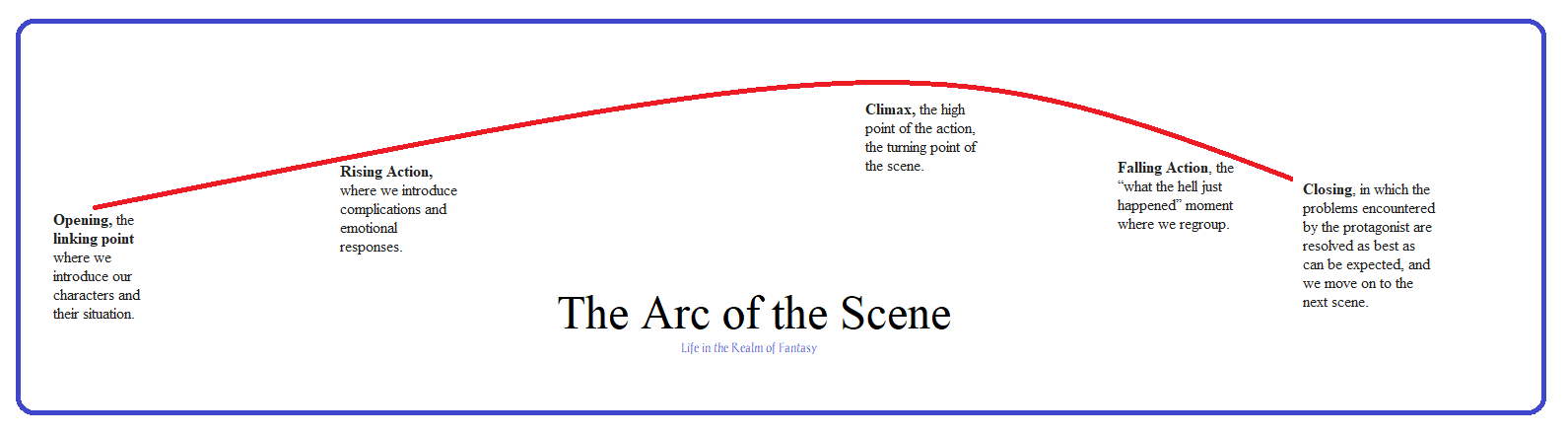

These small arcs of action, reaction, and calm push the plot and ensure it doesn’t stall. Each scene is an opportunity to ratchet up the tension and increase the overall conflict that drives the story. Transition scenes must also have an arc supporting the cathedral that is our novel. They will begin, rise to a peak as the necessary information is discussed, and ebb when the characters move on.

Transition scenes must also have an arc supporting the cathedral that is our novel. They will begin, rise to a peak as the necessary information is discussed, and ebb when the characters move on. Plots are driven by an imbalance of power. The dark corners of the story are illuminated by the characters who have critical knowledge. This is called asymmetric information.

Plots are driven by an imbalance of power. The dark corners of the story are illuminated by the characters who have critical knowledge. This is called asymmetric information. When we write a story, no matter the length, we hope the narrative will keep our readers interested until the end of the book. We lure readers into the scene and reward them with a tiny dose of new information.

When we write a story, no matter the length, we hope the narrative will keep our readers interested until the end of the book. We lure readers into the scene and reward them with a tiny dose of new information. In literary terms, this uneven distribution of knowledge is called asymmetric information. We see this all the time in the corporate world.

In literary terms, this uneven distribution of knowledge is called asymmetric information. We see this all the time in the corporate world. Jared is hilarious, charming, naïve, a bit cocky, and completely unaware that he’s an arrogant jackass. He is a young man who is exceptionally good at everything and is happy to tell you about it. Jared has no clue that his boasting holds him back, as no one wants to work with him.

Jared is hilarious, charming, naïve, a bit cocky, and completely unaware that he’s an arrogant jackass. He is a young man who is exceptionally good at everything and is happy to tell you about it. Jared has no clue that his boasting holds him back, as no one wants to work with him. When I started writing this story, I had the core conflict: Jared’s misguided desire to be important. I had the surface quest: rescuing the kidnapped kid. I had the true quest: Jared learning to laugh at himself and developing a little humility.

When I started writing this story, I had the core conflict: Jared’s misguided desire to be important. I had the surface quest: rescuing the kidnapped kid. I had the true quest: Jared learning to laugh at himself and developing a little humility. assion for the dirty habit of writing every day. They are joining the ranks of the old pros, the people who “do NaNo” every year whether they expect to be published or not.

assion for the dirty habit of writing every day. They are joining the ranks of the old pros, the people who “do NaNo” every year whether they expect to be published or not. In my mind, novels are like Gothic Cathedrals–arcs of stone supporting other arches until you have a structure that can withstand the centuries. Each scene is a tiny arc that supports and strengthens the construct that is our plot.

In my mind, novels are like Gothic Cathedrals–arcs of stone supporting other arches until you have a structure that can withstand the centuries. Each scene is a tiny arc that supports and strengthens the construct that is our plot. Plot points are driven by the characters who have critical knowledge. The fact that some characters are working with limited information creates tension.

Plot points are driven by the characters who have critical knowledge. The fact that some characters are working with limited information creates tension.