Subtext is a complex but essential aspect of storytelling. As the word implies, subtext lies below the surface (sub) and supports the plot and the conversations (text).

It is the hidden story, an unstated knowledge embedded within the narrative.

Subtext can be inserted into the story through the layers of worldbuilding. It is conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

Subtext can be inserted into the story through the layers of worldbuilding. It is conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

We all know good worldbuilding is more than simply detailing the setting. It starts there, but without the addition of mood and atmosphere, a coffee shop is just a room with a few tables and chairs. A reader’s perception of a gripping narrative’s reality is influenced by aspects of the setting that they may not consciously notice at the time.

How does good worldbuilding contribute to good subtext? The clues about mood and atmosphere combine on a subliminal level. This undercurrent shapes a reader’s emotional impressions of the story.

A brief mention of décor can convey atmosphere: Tess stood in line, looking around while Evan secured a table. Country-style furnishings lent a coziness to the room, a warm contrast to the rain pounding on the windows. Soon it was her turn to order. “Two large mochas, please.”

A view of the world from the characters’ point of view is essential, as it conveys mood.

“Why did they bother putting a sign on the dining hall? No matter what Temple you visit, every building is made of white sandstone and you always know where you are and what you are looking at.” Bryson’s scathing tones floated to the instructor, who glared at us all.

Afterward, while readers may not consciously remember details, they will remember what they felt as they read that novel. When asked who their favorite writer is, they will mention that author.

Afterward, while readers may not consciously remember details, they will remember what they felt as they read that novel. When asked who their favorite writer is, they will mention that author.

When we experience emotion, we are feeling the effect of contrasts, of transitioning from the positive (good) to the negative (bad) and back to the positive. Mood, atmosphere, and emotion form the inferential layer of a story, part of the subtext. When an author has done their job well, those transitions feel personal to the reader.

Atmosphere has two aspects: overall and personal. The overall atmosphere of a story is long-term, an element of mood that is conveyed by the setting as well as by the actions and reactions of the characters.

The overall mood of a story is also long-term. It resides in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood shapes (and is shaped by) the emotions evoked within the story.

The inferential layer of a story has another component, one we must look at in the second draft. This is where another aspect of worldbuilding, scene framing, comes into play. This component has two aspects: first, it involves the order in which we stage people and visual objects, as well as the sequence of events along the plot arc. It shapes the overall mood and atmosphere, contributing to the subtext.

inferential layer of a story has another component, one we must look at in the second draft. This is where another aspect of worldbuilding, scene framing, comes into play. This component has two aspects: first, it involves the order in which we stage people and visual objects, as well as the sequence of events along the plot arc. It shapes the overall mood and atmosphere, contributing to the subtext.

The second aspect of scene framing involves the plot arc and how we place the scenes and their transitions. We want them in a logical, sequential order.

Good worldbuilding can help us give backstory without an info dump, and symbolism is a key tool for this. Environmental symbols are subliminal landmarks for the reader. Thinking about and planning symbolism in an environment is crucial to developing the general atmosphere and affecting the overall mood.

For example, the word gothic in a novel’s description tells me it will be a dark, moody piece set in a stark, desolate environment. A cold, barren landscape, constant dampness, and continually gray skies set a somber tone to the background of the scene.

A setting like that underscores each of the main characters’ personal problems and evokes a general atmosphere of gloom.

Our characters’ emotions affect their attitudes toward each other and influence how they view their quest. This, in turn, shapes the overall mood of the characters as they move through the arc of the plot. And the visual atmosphere of a particular environment may affect our protagonist’s personal mood.

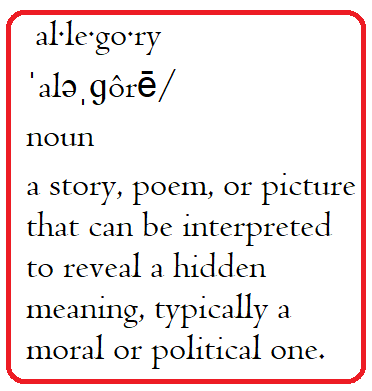

What tools in our writer’s toolbox are effective in conveying an atmosphere and a specific mood? Allegory and symbolism are two devices that are similar but different. The difference between them is how they are presented.

- Allegoryis a moral lesson in the form of a story, heavy with symbolism.

- Symbolismis a literary device that uses one thing throughout the narrative (perhaps shadows) to represent something else (grief).

How can we use allegory and symbolism in modern genre fiction? Cyberpunk, as a subgenre of science fiction, is exceedingly atmosphere-driven. It is heavily symbolic in worldbuilding and often allegorical in the narrative. We see many features of the classic 18th and 19th-century Sturm und Drang literary themes but set in a dystopian society. The deities that humankind must battle are technology and industry. Corporate uber-giants are the gods whose knowledge mere mortals desire and whom they seek to replace.

How can we use allegory and symbolism in modern genre fiction? Cyberpunk, as a subgenre of science fiction, is exceedingly atmosphere-driven. It is heavily symbolic in worldbuilding and often allegorical in the narrative. We see many features of the classic 18th and 19th-century Sturm und Drang literary themes but set in a dystopian society. The deities that humankind must battle are technology and industry. Corporate uber-giants are the gods whose knowledge mere mortals desire and whom they seek to replace.

The setting and worldbuilding in cyberpunk work together to convey a gothic atmosphere. This overall feeling is dark and disturbing. That aspect of subtext is reinforced by the dark nature of interpersonal relationships and the often criminal behaviors our characters engage in for survival.

No matter what genre we write in, the second draft is where we expand on our ideas and fill in the gaps of the rough first draft manuscript. We find words to show the setting more clearly and use visuals to hint at what is to come. We create an immersive atmosphere by including colors, scents, and ambient sounds.

We choose our words carefully as they determine how the visuals are shown. When we have no words and feel stuck, we go to the thesaurus and find them.

Authors are painters, creating worlds out of words. We strive to create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. Each word is a brushstroke that can lighten the mood as easily as it can darken it.

Authors are painters, creating worlds out of words. We strive to create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. Each word is a brushstroke that can lighten the mood as easily as it can darken it.

- When we create a setting, intense color brightens the visuals, and gray depresses them. Those tones affect the atmosphere and mood of the scene.

In the real world, sunshine, green foliage, blue skies, and birdsong go a long way toward lifting my spirits. When I read a scene set in that kind of environment, the mood of the narrative feels lighter to me.

Worldbuilding is complex. It can feel too difficult when we are trying to convey subtext, mood, and atmosphere, using slimmed down prose and power words rather than flowery. But keep at it because the reader won’t be aware of the complexities involved.

All they will know is how strongly the protagonist and her story affected them and how much they loved that novel.

In his book,

In his book,  Truthfully, I find detailed descriptions of facial expressions to be boring and sometimes off-putting. Every author armed with a little knowledge writes characters with curving lips, stretching lips, and lips doing many things over, and over, and over … with little variation.

Truthfully, I find detailed descriptions of facial expressions to be boring and sometimes off-putting. Every author armed with a little knowledge writes characters with curving lips, stretching lips, and lips doing many things over, and over, and over … with little variation. Simplicity has an impact, but I struggle to achieve balance. When looking for words with visceral and emotional power, consonants are your friend. Verbs that begin with consonants are powerful.

Simplicity has an impact, but I struggle to achieve balance. When looking for words with visceral and emotional power, consonants are your friend. Verbs that begin with consonants are powerful. Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood affects (and is affected by) the emotions evoked within the story.

Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood affects (and is affected by) the emotions evoked within the story. Undermotivated emotions lack credibility and leave the reader feeling as if the story is flat. In real life, we have deep, personal reasons for our feelings, and so must our characters.

Undermotivated emotions lack credibility and leave the reader feeling as if the story is flat. In real life, we have deep, personal reasons for our feelings, and so must our characters. Robert McKee tells us that the mood/dynamic of any story is there to make the emotional experience of our characters specific. It makes their emotions feel natural. After all, the mood and atmosphere

Robert McKee tells us that the mood/dynamic of any story is there to make the emotional experience of our characters specific. It makes their emotions feel natural. After all, the mood and atmosphere

![Ruins of the Oybin (Dreamer) – Caspar David Friedrich 1835 [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/caspar_david_friedrich_011.jpg?w=232&h=300)