We are designing a fantasy story, and we are going to write it for us, writing as freely as we want. We’re writing like no one will ever read it but us, so it will be our story, flowing from our vision.

So far, we have created our protagonist and the initial antagonist and have an idea of what their quest is.

We have discovered that our novel might be a Romantasy, as the enemies-to-lovers trope seems to be developing. Now, let’s look at the allies that help our characters as they each strive to fulfill their quest. These are the friends and supporters who enable them to achieve their goals.

We have discovered that our novel might be a Romantasy, as the enemies-to-lovers trope seems to be developing. Now, let’s look at the allies that help our characters as they each strive to fulfill their quest. These are the friends and supporters who enable them to achieve their goals.

The Writer’s Journey, Mythic Structure for Writers, by Christopher Vogler, details the various traditional archetypes that form the basis of most characters in our modern mythology, or literary canon.

The following is the list of character archetypes as described by Vogler:

- Hero: someone who is willing to sacrifice his own needs on behalf of others.

- Mentor: all the characters who teach and protect heroes and give them necessary gifts.

- Threshold Guardian: a menacing face to the hero, but if understood, they can be overcome.

- Herald: a force that brings a new challenge to the hero.

- Shapeshifters: characters who constantly change from the hero’s point of view.

- Shadow: a character who represents the energy of the dark side.

- Ally: someone who travels with the hero through the journey, serving a variety of functions, including that of sacrificial lamb.

- Trickster: embodies the energies of mischief and desire for change.

Side characters are essential, especially characters with secrets because they are a mystery. Readers love to work out puzzles. However, the job of the supporting cast is to keep the attention focused on the protagonist and the antagonist and their quest.

![]() For that reason, I recommend keeping the number of allies limited. Too many named characters can lead to confusion in the reader. For the sake of simplicity, I am limiting the number of characters in each party to 3 trusted cohorts.

For that reason, I recommend keeping the number of allies limited. Too many named characters can lead to confusion in the reader. For the sake of simplicity, I am limiting the number of characters in each party to 3 trusted cohorts.

The quest is simple: Our protagonist and antagonist are co-regents of twelve-year-old King Edward. Both seek to keep him alive, but they have radically different ideas about his upbringing. Both believe the other is the cause of Edward’s wasting illness.’

At this point in the planning process, Edward is a MacGuffin, and if he has a personality, it will emerge as time goes on. So, how does Val’s party line up?

- First is the ally who is also the trickster. This character is as yet unnamed, but they are the core of Val’s spy network and will be fun to write. This ally will also serve as the sacrificial lamb, bringing pathos into the story.

- Val’s second in command fills the role of paladin, a common fantasy character trope. He is a trusted officer in the royal guards. He does not trust the spy, bringing friction and mutual distrust into play and offering opportunities for our spy to vent his humor at the paladin’s expense.

- Val’s third ally is a healer, a woman who was young King Edward’s nurse when he was a baby. She also has the role of mentor when wisdom is required.

Our sidekicks are as yet unnamed, BUT we might have our novel made into an audiobook. Thus, we must consider ease of pronunciation when a name is read aloud.

Every core character that the protagonists are surrounded by should project an unmistakable surface persona, characteristics that a reader will recognize as unique from the outset.

Every core character that the protagonists are surrounded by should project an unmistakable surface persona, characteristics that a reader will recognize as unique from the outset.

Kai Voss will also have three trusted allies.

- Kai’s much older (illegitimate) half-brother is also a sorcerer and has long served as Kai’s mentor. He is also the Shadow, the suave, worldly character who subtly brings the energy of the dark side.

- Two soldiers have sided with Kai, both firmly believing they are the salvation of the young king. One is the paladin, a man who believes in honor and loyalty to the king and the traditions that he believes in.

- One soldier has the role of herald and will be the sacrificial lamb when he uncovers an uncomfortable truth.

From the moment they enter the story, we should see glimpses of weaknesses and fears. We should see hints of the sorrows and guilts that lie beneath their exterior personas. These characters are not the protagonist, so their backstory must emerge as a side note, a justification for their inclusion in the core group.

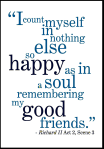

Old friends have long histories, and the protagonist knows most of their secrets at the outset—but perhaps not all. Unspoken secrets will emerge only at critical points if and when they affect the protagonist or antagonist, and only if they provide the reader with information they must know.

If these friends are new to the protagonist, their stories should emerge in the form of information needed to complete the quest.

In real life, everyone has emotions and thoughts they conceal from others. Perhaps they are angry and afraid, or jealous, or any number of emotions we are embarrassed to acknowledge. Maybe they hope to gain something on a personal level. If so, what? Small hints revealing those unspoken motives are crucial to raising the tension in the narrative.

As writers, our task is to ensure that each character’s individual story intersects smoothly and doesn’t jar the reader.

As writers, our task is to ensure that each character’s individual story intersects smoothly and doesn’t jar the reader.

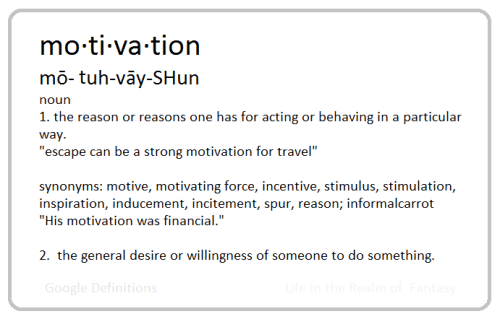

To do that, the motivations of the side characters must be clearly defined. You must know how the person thinks and reacts as an individual.

Ask yourself what deep desires push this character onward? Just as you have done with the hero of your story, ask yourself what the side characters’ moral boundaries are and what actions would be out of character for them?

- Write nothing that seems out of character unless there is a good, justified reason for that behavior or comment.

We want to create empathy in the reader for the group as a whole, but we want to keep the pace of the plot arc moving forward.

Certain plot tricks function well across all genres, from sci-fi to romance, no matter the setting. In most novels, one or more characters are “fish out of water” in that they are immediately thrust into an unfamiliar and possibly dangerous environment.

In our current manuscript, it is our antagonist, Kai Voss, who will be thrust into the unknown by a traitor acting on their secret agenda, and we will talk about that in our next installment.

As stories unfold on paper, new characters enter. They bring their dramas and the story goes in a different direction than was planned. When I meet these imaginary people, I assign their personalities a verb and a noun.

As stories unfold on paper, new characters enter. They bring their dramas and the story goes in a different direction than was planned. When I meet these imaginary people, I assign their personalities a verb and a noun. Julian’s noun is chivalry (Gallantry, Bravery, Daring, Courtliness, Valor, Love). He sees himself as a good knight and puts all his effort into being that person. He is in love with both Mags and Beau.

Julian’s noun is chivalry (Gallantry, Bravery, Daring, Courtliness, Valor, Love). He sees himself as a good knight and puts all his effort into being that person. He is in love with both Mags and Beau. Next, we assign a verb that describes their gut reactions, which will guide how they react to every situation. They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth. Again, we also look at sub-verbs and synonyms:

Next, we assign a verb that describes their gut reactions, which will guide how they react to every situation. They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth. Again, we also look at sub-verbs and synonyms: Have you thought about the two words that describe the primary weaknesses of your characters, the thing that could be their ultimate ruin? In the case of Julian’s story, it was:

Have you thought about the two words that describe the primary weaknesses of your characters, the thing that could be their ultimate ruin? In the case of Julian’s story, it was: Julian Lackland took ten years to get from the 2010 NaNoWriMo novel to the finished product. He spawned the books

Julian Lackland took ten years to get from the 2010 NaNoWriMo novel to the finished product. He spawned the books

I write what I am in the mood to read, so my genre is usually a fantasy of one kind or another. However, I sometimes go nuts and write women’s fiction.

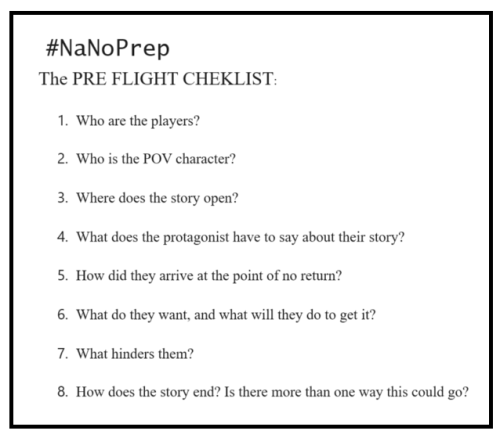

I write what I am in the mood to read, so my genre is usually a fantasy of one kind or another. However, I sometimes go nuts and write women’s fiction. But regardless of the genre, the basic premise of any story can be answered in eight questions that we will ask of the characters.

But regardless of the genre, the basic premise of any story can be answered in eight questions that we will ask of the characters.

No matter how many characters you think are involved, one will stand out. That person will be the protagonist.

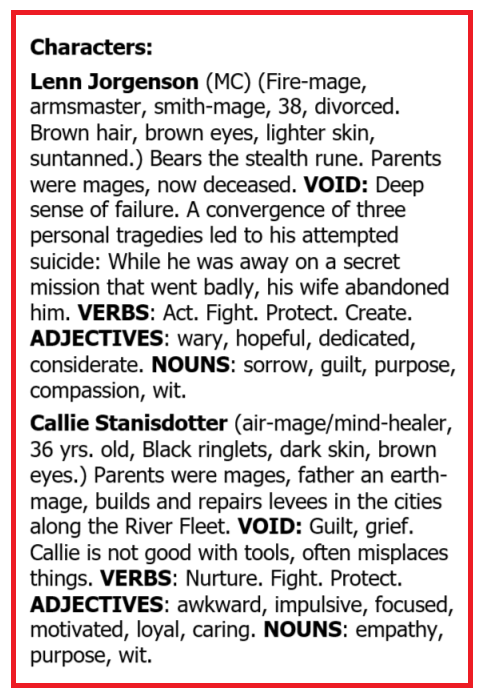

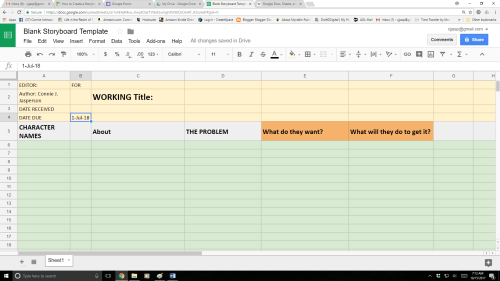

No matter how many characters you think are involved, one will stand out. That person will be the protagonist. Once I know the basic plot, I make a page in my workbook with a bio of each character, a short personnel file. Sometimes, I include images of RPG characters or actors who most physically resemble them and who could play them well—but this is only to cement them in my mind.

Once I know the basic plot, I make a page in my workbook with a bio of each character, a short personnel file. Sometimes, I include images of RPG characters or actors who most physically resemble them and who could play them well—but this is only to cement them in my mind. Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as more intense than one whose name starts with a soft sound. It’s a little thing, but it is something to consider when conveying personalities.

Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as more intense than one whose name starts with a soft sound. It’s a little thing, but it is something to consider when conveying personalities.

But we all know infodumps are an insidious poison, so how do we apply this backstory without losing the reader?

But we all know infodumps are an insidious poison, so how do we apply this backstory without losing the reader? Character A is a shaman, a fire-mage smith and warrior, and is slated to be the next War Leader of the tribes. His shamanic purpose is to unite the people, both the tribes and those citadels who have turned tribeless. He is the chosen champion of the Goddess his sect of mages serves, and his success or failure will determine her fate.

Character A is a shaman, a fire-mage smith and warrior, and is slated to be the next War Leader of the tribes. His shamanic purpose is to unite the people, both the tribes and those citadels who have turned tribeless. He is the chosen champion of the Goddess his sect of mages serves, and his success or failure will determine her fate. This void is vital because characters must overcome fear to face it. As a reader, one characteristic I’ve noticed in my favorite characters is they each have a hint of self-deception. All the characters – the antagonists and the protagonists – deceive themselves in some way about their own motives.

This void is vital because characters must overcome fear to face it. As a reader, one characteristic I’ve noticed in my favorite characters is they each have a hint of self-deception. All the characters – the antagonists and the protagonists – deceive themselves in some way about their own motives.

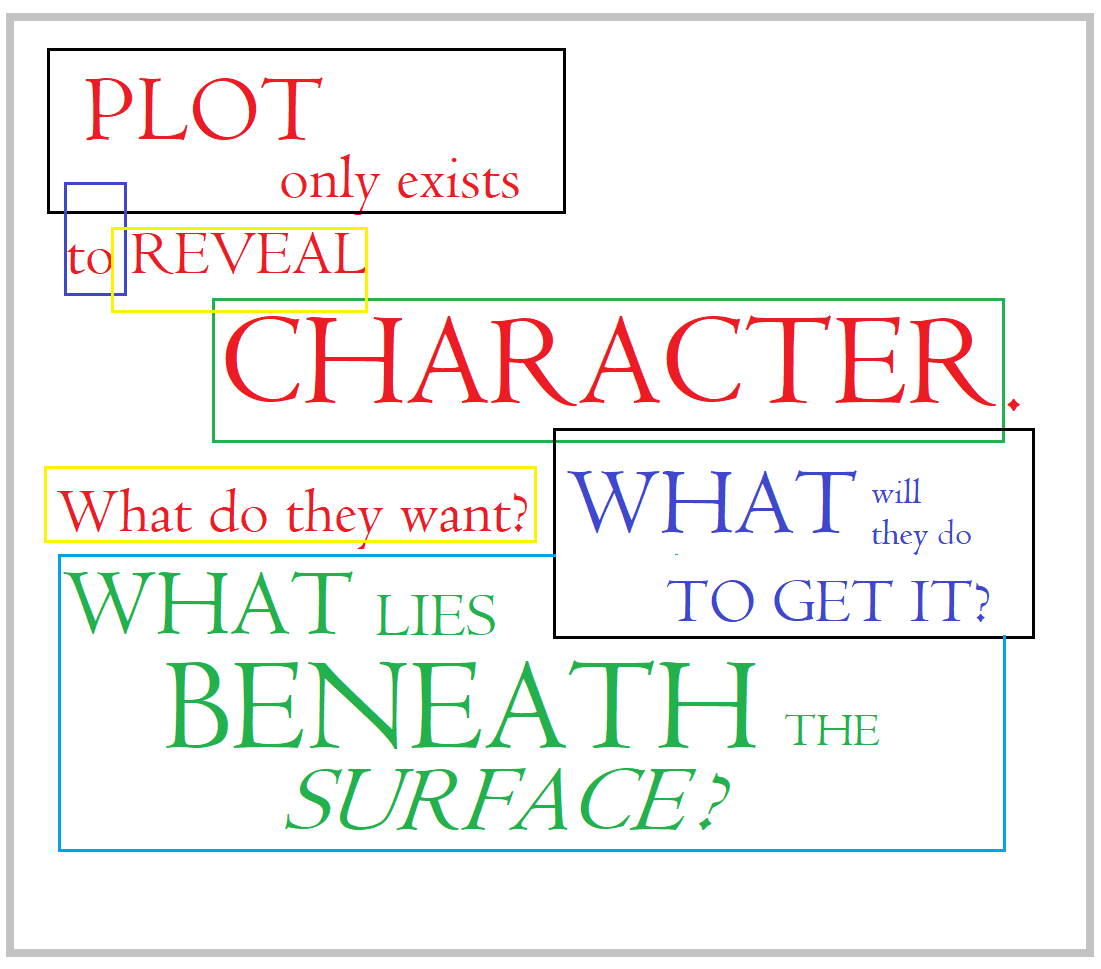

When I plan a character, I make a simple word picture of them. The word picture is made of a verb and a noun, the two words that best describe each person.

When I plan a character, I make a simple word picture of them. The word picture is made of a verb and a noun, the two words that best describe each person. When I write my characters, I know how they believe they will react in a given situation. Why? Because I have drawn their portraits using words:

When I write my characters, I know how they believe they will react in a given situation. Why? Because I have drawn their portraits using words: Sometimes the path to publication is fraught with misery; next week, we will discuss that. Other times, the book writes itself and flies out the door. Who knows how my next novel will go?

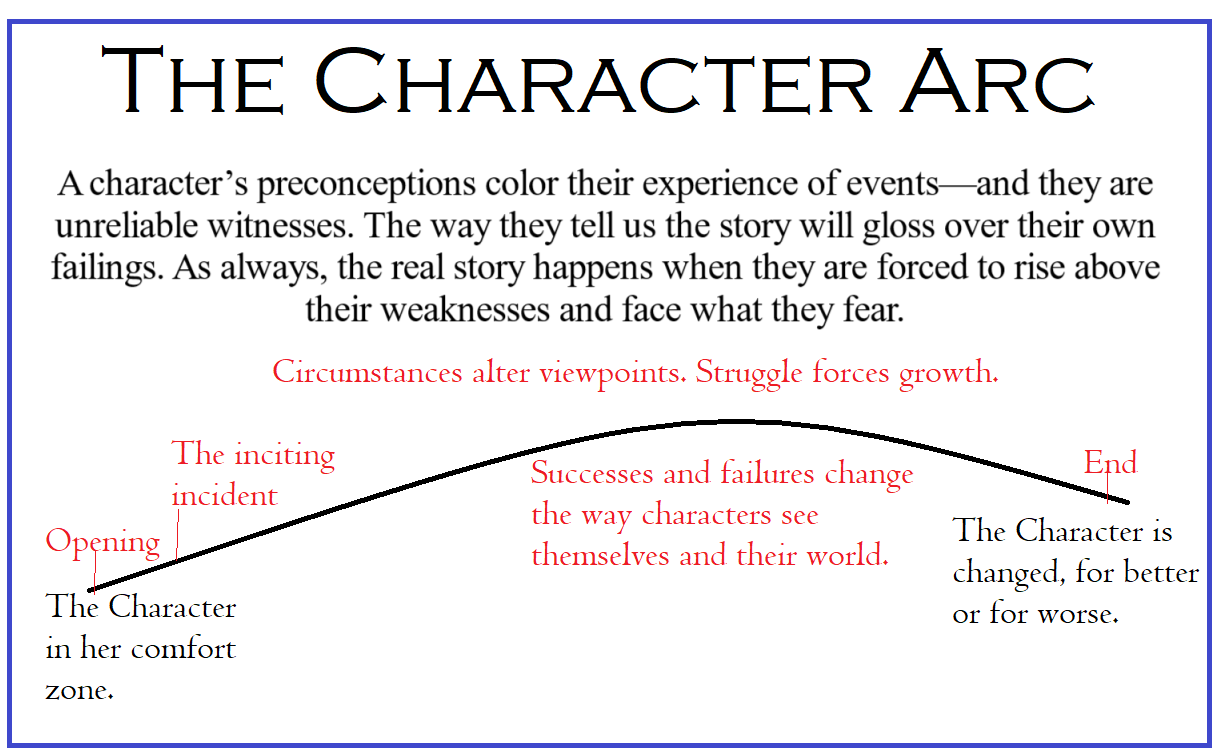

Sometimes the path to publication is fraught with misery; next week, we will discuss that. Other times, the book writes itself and flies out the door. Who knows how my next novel will go? A character’s preconceptions color their experience of events. We readers see the story through their eyes, which shades how we perceive the incidents.

A character’s preconceptions color their experience of events. We readers see the story through their eyes, which shades how we perceive the incidents. This is a literary theme and is known as the hero’s journey. But it is only the overarching theme. For that hero’s main character arc to work, they need subthemes.

This is a literary theme and is known as the hero’s journey. But it is only the overarching theme. For that hero’s main character arc to work, they need subthemes. What is the “hero’s journey” and why am I so fond of it?

What is the “hero’s journey” and why am I so fond of it?  When

When Other novels are entirely character-driven, focusing on the protagonist of the narrative. Much thought is given to how prose is crafted stylistically, using a wide vocabulary. These novels feature thoughtful, in-depth character studies of complex, often troubled, characters. The story is in their day-to-day dealings with these issues. Action is less important than introspection, and the setting frames the characters and their arcs of growth.

Other novels are entirely character-driven, focusing on the protagonist of the narrative. Much thought is given to how prose is crafted stylistically, using a wide vocabulary. These novels feature thoughtful, in-depth character studies of complex, often troubled, characters. The story is in their day-to-day dealings with these issues. Action is less important than introspection, and the setting frames the characters and their arcs of growth. Let’s look again at J.R.R. Tolkien’s

Let’s look again at J.R.R. Tolkien’s  When we are constantly prodded to make our work focus on action and events, it becomes easy to forget that characters have an internal arc. They must grow for good or ill.

When we are constantly prodded to make our work focus on action and events, it becomes easy to forget that characters have an internal arc. They must grow for good or ill. I step away from my project for a week or two or even longer when stuck. When I come back to it, the characters and their journey is new again, inspiring me to finish their story. This is why I am a slow writer.

I step away from my project for a week or two or even longer when stuck. When I come back to it, the characters and their journey is new again, inspiring me to finish their story. This is why I am a slow writer. Do you write your heroes with few flaws, or do you portray them as “warts and all?” That becomes a matter of what you want to read.

Do you write your heroes with few flaws, or do you portray them as “warts and all?” That becomes a matter of what you want to read. Still, I write stories about people who might have existed and have their own views of morality. In each tale, I try to get into the characters’ heads. I want to understand why they sometimes make terrible choices, acts that profoundly change their lives.

Still, I write stories about people who might have existed and have their own views of morality. In each tale, I try to get into the characters’ heads. I want to understand why they sometimes make terrible choices, acts that profoundly change their lives. To me, the flawed hero has much to offer us. In my most recently published book, a stand-alone novel called

To me, the flawed hero has much to offer us. In my most recently published book, a stand-alone novel called

The difference between the antagonist and the hero is the amount of grayness in their moral compass. When does the gray area of morality begin edging toward genuinely dark? What are they not willing to do to achieve their goal?

The difference between the antagonist and the hero is the amount of grayness in their moral compass. When does the gray area of morality begin edging toward genuinely dark? What are they not willing to do to achieve their goal?