Sometimes we find that our work-in-progress is not really a novel after all. We get to the finish point, and that place might be only at the 40,000-word mark (or less).

In some circles, 40,000 words is a novel, but in fantasy, it is less than half a book. A short novel that has been read to shreds is far better than a long, boring book ending its days as a doorstop.

I recommend not trying to stretch the length if you have nothing of value to add to the tale. It’s better to be known for having written a strong novella than a weak novel. So, now at the end of the rough draft, your book must become a novella.

In the second draft, you will weed out many words and cut the unnecessary repetitions. The manuscript is going to both expand and contract, but when the final ms is complete, it may be only 35,000 words. But why do I think this?

I have experienced this very thing. Sometimes, when I was just finishing the rough draft, I discovered that besides the four chapters that had to go since they don’t belong there anymore, 3 more chapters were mostly background, rambling to get my personal mindset into the story. That sort of background doesn’t need to be in the finished product, other than a brief mention in conversation. Often, when I go in and remove large chunks of exposition, I’m able to condense those chapters into one passage or scene that actually moves the story forward.

Another thing to watch for when you are in the second draft, are areas where you may have repeated yourself, with a slightly different phrasing. These are hard for the author to pick out, but they can be found. Decide which phrasing you like the best, and go with that.

Also in the rough draft, we use a lot of words we can cut or find alternatives for, words and phrases that weaken our narrative:

- There was

- To be

We change these words to more active phrasing, and sometimes we gain a few words in the process.

In conversations especially, it’s good to use contractions. ‘Was not’ becomes ‘wasn’t,’ ‘has not becomes hasn’t,’ etc.

It’s amazing how many times we can simply cut some words out, and find the prose is stronger without them. Many times they need no replacement.

Sometimes we use what I think of as “crutch” words. You can really lower your word-count when you look at each instance and see if you can get rid of these words. These are overused words that fall out of our heads along with the good stuff as we are sailing along:

- so,

- very,

- that,

- just,

- literally

- very

The fact is, you must be willing to be ruthless. Yes, you may well have spent three days or even weeks writing a chapter you are about to cut. But now that you see it in the context of the overall story arc, you realize it is bogging things down, and NO–Sometimes there is no fixing it. Just because we wrote something does not mean we have to keep it in the story.

But do save it in a separate file, as you may be able to use it later. I always have a file folder labeled “Outtakes.” Many times those cut pieces become the core of a new story.

I strongly feel that no matter how much you like the prose you have just written for a given chapter, if the chapter or passage does not advance the story, it must go.

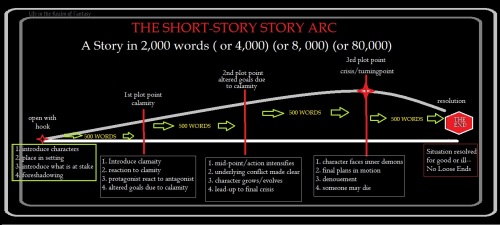

Pay close attention to the story arc. Large chunks of exposition flatten it, pushing the plot point back, and the reader may give up. Once you have your rough draft complete, measure the tale against the blueprint of the story arc.

- Where does the inciting incident occur?

- Where does the first pinch point occur?

- What is happening at midpoint? Are the events of the middle section moving the protagonist toward their goal?

- Where does the third plot point occur?

It’s not important to have written a novel. Whether you write short stories or 700-page doorstops, you are an author. It is, however, extremely important to have written well. A powerful, well-written novella can be a reading experience that shakes the literary world:

- A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens

- Breakfast at Tiffany’s, by Truman Capote

- Candide, by Voltaire

- Three Blind Mice, by Agatha Christie

- The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Robert Louis Stevenson

- The Time Machine, by H.G, Wells

- Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck

- The Old Man and the Sea, by Ernest Hemingway

- Animal Farm, by George Orwell

- The Turn of the Screw, by Henry James