Last week, we talked about transition scenes. We talked about how the resolution of one event takes us to a linking point that takes us further into the story. We talked about how, without transition scenes to link them, moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together. They push the plot forward. Action, transition, action, transition—this is pacing.

But how do we recognize when a moment of action has true dramatic potential? We try to inject action and emotion into our scenes, but some dramatic events don’t advance the story.

But how do we recognize when a moment of action has true dramatic potential? We try to inject action and emotion into our scenes, but some dramatic events don’t advance the story.

- How do we recognize when an action scene is not crucial, not central to the overall plot arc?

I find that my writing group is essential in helping me eliminate the scenes that don’t move the plot forward, even though they might be engaging stories within the story.

It’s easy to be so attached to a particular scene that we don’t notice that it’s a side quest to nowhere.

If that happens to you, don’t throw it out! Save it in a file labeled “outtakes,” and with a few minor changes, you can reuse that idea elsewhere. A side quest might slow down the pacing of one story. But that quest, with different characters and places, could be the seed of an entirely different story.

Recognizing where the real drama begins is tricky. Let’s have a look at the novel Possession: A Romance by A.S. Byatt (pen name of the late Dame Antonia Susan Duffy DBE), winner of the 1990 Booker Prize.

Recognizing where the real drama begins is tricky. Let’s have a look at the novel Possession: A Romance by A.S. Byatt (pen name of the late Dame Antonia Susan Duffy DBE), winner of the 1990 Booker Prize.

The story details two complex relationships viewed across time. The modern relationship begins in an unexpected way. The novel opens in a library, a place of silence and solitude where one would think the only opportunity for drama is within the pages of the tomes lining the shelves.

But Byatt saw the potential for real drama in that quiet, dusty place. Her protagonist, Roland Michell, a scholar and professional man of high morals, commits a crime. There isn’t anything exciting about a professor sitting in a library and researching the lives of dead poets—that is, until he pockets the original drafts of letters he has come across in his research.

A person unfamiliar with academic research might not understand how such a small, seemingly inconsequential theft could possibly have a dire outcome.

- This is the moment that has the potential of ruining his career, destroying everything he has worked for.

- The consequences of this act hang over him to the end.

About the book, via Wikipedia:

The novel follows two modern-day academics as they research the paper trail around the previously unknown love life between famous fictional poets Randolph Henry Ash and Christabel LaMotte. Possession is set both in the present day and the Victorian era, contrasting the two time periods, as well as echoing similarities and satirizing modern academia and mating rituals. The structure of the novel incorporates many different styles, including fictional diary entries, letters and poetry, and uses these styles and other devices to explore the postmodern concerns of the authority of textual narratives. The title Possession highlights many of the major themes in the novel: questions of ownership and independence between lovers; the practice of collecting historically significant cultural artifacts; and the possession that biographers feel toward their subjects.

AS. Byatt, in part, wrote Possession in response to John Fowles‘ novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman(1969). In an essay in Byatt’s nonfiction book, On Histories and Stories, she wrote:

“Fowles has said that the nineteenth-century narrator was assuming the omniscience of a god. I think rather the opposite is the case—this kind of fictive narrator can creep closer to the feelings and inner life of characters—as well as providing a Greek chorus—than any first-person mimicry. In ‘Possession’ I used this kind of narrator deliberately three times in the historical narrative—always to tell what the historians and biographers of my fiction never discovered, always to heighten the reader’s imaginative entry into the world of the text.” [1]

So, Byatt changes narrative point of view in this tale when necessary, as a means to better explore an aspect of the story. That is a neat trick, if done right, which she does. (Done wrong, it has the potential of adding chaos to the narrative.)

I admire the audacity of having Michell, a protagonist who considers his professional reputation as his most prized possession, commit such a catastrophic action as stealing those original letters. It proves there is potential for drama in the least likely places.

I admire the audacity of having Michell, a protagonist who considers his professional reputation as his most prized possession, commit such a catastrophic action as stealing those original letters. It proves there is potential for drama in the least likely places.

I have been known to spend months writing the wrong story.

Instead of following the original outline, I took the plot off on a tangent and wrote myself into a corner. Then, once I admitted to myself that there was no rescuing it, I moved on to something else.

Most writers don’t see where they’ve gone awry until someone else points it out, or they step away from it for a while.

Once I give up and set a work that is stalled aside for a month or two, these things are easier to see. In the case of one novel, I cut it back to the 20,000-word mark and made a new, more logical outline. Writing went well after that, and so far, I’m getting good, useable feedback.

Creators see their work the way parents see their children. We tend to think every scene is golden. Unfortunately, some events I might believe are necessary—aren’t.

In reality, they lead the story nowhere.

courtesy Office 360 graphics

But I love my children, even the unruly ones. Nothing is a waste of time, and those scenes become the basis of novellas and short stories.

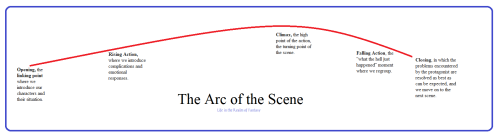

The ability to recognize the potential for a crucial dramatic moment is a matter of perspective. It is the ability to see the story arc as a whole before it is fully formed.

It is also the knack of knowing what kind of drama the story needs and where it should fit within the plot arc.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Possession (Byatt novel),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Possession_(Byatt_novel)&oldid=1189753614 (accessed March 19, 2024).

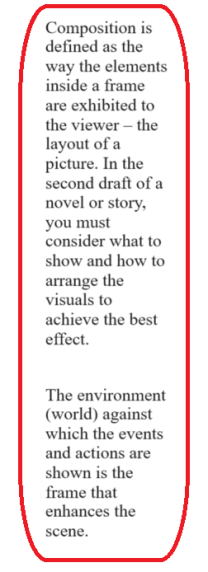

In a novel or story, each scene occurs within the framework of the environment.

In a novel or story, each scene occurs within the framework of the environment. The Dragonriders of Pern series is considered science fiction because McCaffrey made clear at the outset that the star (Rukbat) and its planetary system had been colonized two millennia before, and the protagonists were their descendants.

The Dragonriders of Pern series is considered science fiction because McCaffrey made clear at the outset that the star (Rukbat) and its planetary system had been colonized two millennia before, and the protagonists were their descendants. The scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them. In both settings, the surroundings do the dramatic heavy lifting. This chapter is filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted.

The scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them. In both settings, the surroundings do the dramatic heavy lifting. This chapter is filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted. Sallah enters the shuttle just as the airlock door closes, catching and crushing her heel. She manages to pull it out so that she isn’t trapped, but she is severely injured.

Sallah enters the shuttle just as the airlock door closes, catching and crushing her heel. She manages to pull it out so that she isn’t trapped, but she is severely injured. This is an incredibly emotional scene: we are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her last breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground.

This is an incredibly emotional scene: we are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her last breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground.