In any narrative, the shadow provides opportunities for the plot. Whether it is a person, a creature, or a natural disaster, the antagonist represents darkness (evil), against which light (good) is shown more clearly.

Best of all, the shadow, whether a person, place, or thing, provides the roadblocks, the cause to hang a plot on.

When the antagonist is a person, I ask myself, what drives them to create the roadblocks they do? Why do they feel justified in doing so?

If you are writing a memoir, who or what is the antagonist? Memoirs are written to shed light on the difficulties the author has overcome, so who or what frustrated your efforts? (Hint: for some autobiographies, it is a parent or guardian. Other times it is society, the standards and values we impose on those who don’t fit into the slots designated for them.)

In a character-driven novel, there may be two enemies, one of which is the protagonist’s inhibitions and self-doubt.

Many times, two main characters have a sharply defined good versus evil chemistry—like Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty. (Trust me, the antagonist is a main character, or the hero has nothing to struggle against.)

The characters on both sides of the battle must recognize and confront the darkness within themselves. They must choose their own path—will they fight to uphold the light? Or will they turn toward the shadow?

When the protagonist must face and overcome the shadow on a profoundly personal level, they are placed in true danger. The reader knows that if the hero strays from the light, they will become the enemy’s tool.

The best shadow characters have many layers, and not all of them are bad. They are charismatic because we can relate to their struggle. We might hope events will change them for the better but know in our hearts they won’t.

The best shadow characters have many layers, and not all of them are bad. They are charismatic because we can relate to their struggle. We might hope events will change them for the better but know in our hearts they won’t.

Antagonists must be fleshed out. Characters portrayed as evil for the sake of drama can be cartoonish. Their actions must be rational, or the reader won’t be able to suspend their disbelief.

The most fearsome villains have deep stories. Yes, they may have begun life as unpleasant children and may even be sociopaths. Something started them down that path, reinforcing their logic and reasoning.

When the plot centers around the pursuit of a desired object, authors will spend enormous amounts of time working on the hero’s reasons for the quest. They know there must be a serious need driving their struggle to acquire the Golden McGuffin.

Where we sometimes fail is in how we depict the enemy. The villain’s actions must also be plausible. There must be a kind of logic, twisted though it may be, for going to the lengths they do to thwart our heroes.

A mere desire for power is NOT a good or logical reason unless it has roots in the enemy’s past. Why does Voldemort desire that power? What fundamental void drives them to demand absolute control over every aspect of their life and to exert control over the lives of their minions?

The characters in our stories don’t go through their events and trials alone. Authors drag the reader along for the ride the moment they begin writing the story. So, readers want to know why they’ve been put in that handbasket, and they want to know where the enemy believes they’re going. Otherwise, the narrative makes no sense and we lose the reader.

Most of us know what motivates our protagonist. But our antagonist is frequently a mystery, and the place where the two characters’ desires converge is a muddle. We know the what, but the why eludes us.

This can make the antagonist less important to the plot than the protagonist. When we lose track of the antagonist, we are on the road to the dreaded “mushy middle,” the place where the characters wander around aimlessly until an event happens out of nowhere.

The reader must grasp the reasoning behind the enemy’s actions, or they won’t be able to suspend their disbelief.

Ask yourself a few questions:

- What is their void? What made our antagonist turn to the darkness?

- What events gave our antagonist the strength and courage to rise above the past, twisted though they are?

- What desire drives our antagonist’s agenda?

- What does our antagonist hope to achieve?

- Why does our antagonist believe achieving their goal will resolve the wrongs they’ve suffered?

None of this backstory needs to be dumped into the narrative. It should be written out and saved as a separate document and brought out when it is needed. The past must emerge in tantalizing bits and hints as the plot progresses and conversations happen.

The hero’s ultimate victory must evoke emotion in the reader. We want them to think about the dilemmas and roadblocks that all the characters have faced, and we want them to wish the story hadn’t ended.

The villains we write into our stories represent humanity’s darker side, whether they are a person, a dangerous animal, or a natural disaster. They bring ethical and moral quandaries to the story, offering food for thought long after the story has ended.

Ideas slip away unless I get them on paper first, so I create a separate document that is for my use only, and I label it appropriately:

BookTitle_Plot_CoreConflict.docx

It’s a synopsis of the conflict boiled down to a few paragraphs. Whenever I find myself wondering what the hell we’re supposed to be doing, I refer back to it.

In my current unfinished work-in-progress, Character A, my protagonist, represents teamwork succeeding over great odds. Character B, my villain, represents the quest for supremacy at all costs.

- Each must see themselves as the hero.

- Each must risk everything to succeed.

- Each must believe or hope that they will ultimately win.

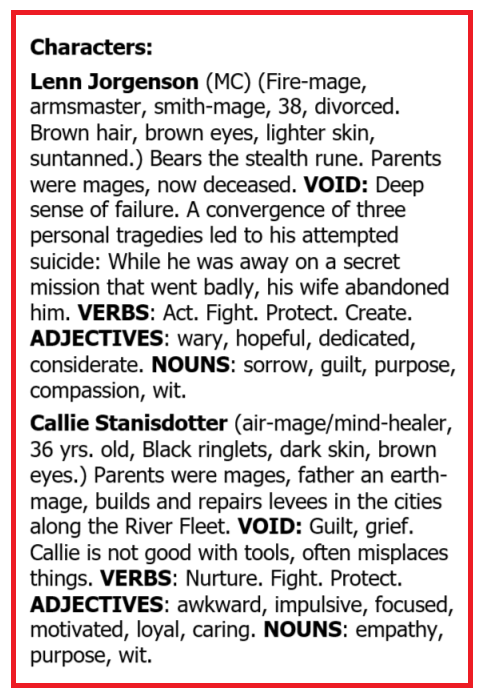

When I create a personnel file for my characters, I assign them verbs, nouns, and adjectives that best show the traits they embody. Verbs are action words that show a character’s gut reactions. Nouns describe personalities best when they are combined with strong verbs.

They must also have a void – an emotional emptiness, a wound of some sort. In my current WIP, Character B fell victim to a mage-trap. He knows he has lost something important, something that was central to him. But he refuses to believe he is under a spell of compelling, a pawn in the Gods’ Great Game. He must believe he has agency—this is his void.

This void is vital because characters must overcome fear to face it. As a reader, one characteristic I’ve noticed in my favorite characters is they each have a hint of self-deception. All the characters – the antagonists and the protagonists – deceive themselves in some way about their own motives.

My task is to ensure that the stories of Characters A and B intersect seamlessly. Motivations must be clearly defined so the reader knows what their moral boundaries are. I like to know their limits because even cartoon supervillains draw the line somewhere.

For me, plots tend to evolve once I begin picturing the characters’ growth arcs. How do I see them at the beginning? How do I see them at the end?

As I write the narrative, they will evolve and change the course of what I thought the original plot was. Sometimes it will change radically. But at some point, the plot must settle into its final form.

I love a novel with a plot arc that explores the protagonist’s struggle against a fully developed, believable adversary, one we almost regret having to defeat.

If you are currently working on a manuscript that feels stuck, I hope this discussion helps you in some way. Good luck and happy writing!

In his book,

In his book,  Batman is a

Batman is a  Apollo 13 (April 11–17, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the

Apollo 13 (April 11–17, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the  You’ve taken them through two revisions and think these characters are awesome, perfectly drawn as you intend. The overall theme of the narrative supports the plot arc, and the events are timed perfectly, so the pacing is good.

You’ve taken them through two revisions and think these characters are awesome, perfectly drawn as you intend. The overall theme of the narrative supports the plot arc, and the events are timed perfectly, so the pacing is good. But in real life, I often find little distinction between heroes and villains. Heroes are often jackasses who need to be taken down a notch. Villains will extort protection money from a store owner and then turn around and open a soup kitchen to feed the unemployed.

But in real life, I often find little distinction between heroes and villains. Heroes are often jackasses who need to be taken down a notch. Villains will extort protection money from a store owner and then turn around and open a soup kitchen to feed the unemployed. Both heroes and villains must have possibilities – the chance that the villain might be redeemed, or the hero might become the villain. As an avid gamer, I think of this as the “

Both heroes and villains must have possibilities – the chance that the villain might be redeemed, or the hero might become the villain. As an avid gamer, I think of this as the “ In Final Fantasy VII, the 1997 game that started it all, we meet Cloud Strife, a mercenary with a mysterious past. Gradually, we discover that, unbeknownst to himself, he is living a lie that he must face and overcome to be the hero we all need him to be.

In Final Fantasy VII, the 1997 game that started it all, we meet Cloud Strife, a mercenary with a mysterious past. Gradually, we discover that, unbeknownst to himself, he is living a lie that he must face and overcome to be the hero we all need him to be.