The month of September is drawing to a close, and we are winding up our dive into the second draft of a manuscript. We hope we have a perfect manuscript with no structural issues.

But we know the work is just beginning. Now we need an unbiased eye looking at the structure, a beta reader.

But we know the work is just beginning. Now we need an unbiased eye looking at the structure, a beta reader.

Beta Reading is the first look at a manuscript by someone other than the author. It is the first reading of an early draft by an unbiased eye. Editing and proofreading happen further down the process, but this reading is critical.

This phase should guide the author in making revisions that make the story stronger. It’s best when the reader is a person who reads for pleasure and can gently express what they think about a story or novel.

I do suggest you find a person who enjoys the genre of that particular story. If you are asked to be a beta reader, you should know it is not a final draft. You should ask several questions as you read:

Setting: Does the setting feel real?

Setting: Does the setting feel real?- Characters: Is the point of view character (protagonist) clear? Did you understand what they were feeling? Were they likable? Did you identify with and care about them? Were there various character types, or did they all seem the same? Were their emotions and motivations clear and relatable?

- Dialogue: Did the dialogue and internal narratives advance the plot?

- Events: did the inciting incident and subsequent roadblocks to success feel believable?

- Pacing: How did the momentum feel?

- Does the ending surprise and satisfy you? What do you think might happen next?

If you are asked to be a beta reader, you might be distracted by grammar and mechanics, and you might forget that the manuscript you’ve been asked to read is unedited.

- I suggest you keep editorial comments broad, as a line edit is not what the author is looking for at this stage.

However, if the author really has no understanding of grammar and mechanics, you might gently direct them to an online grammar guide, such as The Chicago Manual of Style Online.

I am fortunate to have excellent friends in my writing group who are willing to read for me. Their suggestions are thoughtful and spot-on.

Let’s say that you have just joined a professional writers’ group. After attending a few meetings, you ask a member for feedback about your book or short story.

Be prepared for it to come back with some detailed critical observations, which may seem harsh. Any criticism of our life’s work feels unfair to an author who is new at this. And to be truthful, some authors never learn how to put aside their egos.

Be prepared for it to come back with some detailed critical observations, which may seem harsh. Any criticism of our life’s work feels unfair to an author who is new at this. And to be truthful, some authors never learn how to put aside their egos.

Some authors read the first three comments, decide the reader missed the point, and choose to ignore all the suggestions.

This is because the reader pointed out info dumps and long paragraphs the author thought were essential to the why and wherefore of things.

Worse, perhaps they were familiar with a featured component of the story, such as medicine or police procedures. The reader might have suggested we need to do more research and then rewrite what we thought was the perfect novel.

Worse, perhaps they were familiar with a featured component of the story, such as medicine or police procedures. The reader might have suggested we need to do more research and then rewrite what we thought was the perfect novel.

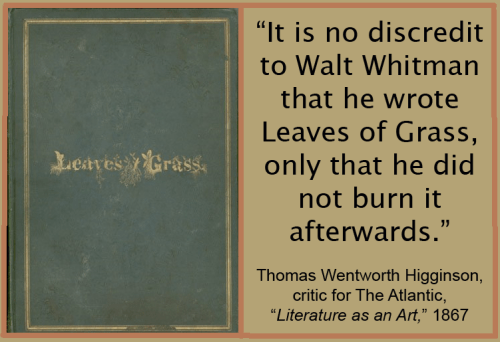

Even if it is worded kindly, criticism can make you feel like you have failed.

When I received my first critique, I was stunned, embarrassed, and deeply confused. I had worked and worked on that manuscript and why didn’t they know that?

Being the only one in a group who didn’t understand something made me angry, but thank heavens, my manners kicked in. I bottled it up and behaved myself.

Not understanding how to correct our bad writing habits is the core reason why we feel so hurt.

That critique was painful, but when I look back on it, I can clearly see why the manuscript was not acceptable in the state it was in.

I had no idea what a finished manuscript should look like, nor did I understand how to get it to look that way. I didn’t know where to begin or who to turn to for answers.

- I didn’t understand how to write to a particular theme.

- Punctuation and usage were inconsistent and showed I lacked an understanding of basic grammar rules.

- I resented being told I used clichés.

- I resented being told my prose was passive. But I couldn’t understand what they meant when they said to write active prose.

There was only one way to resolve this problem. I had to educate myself.

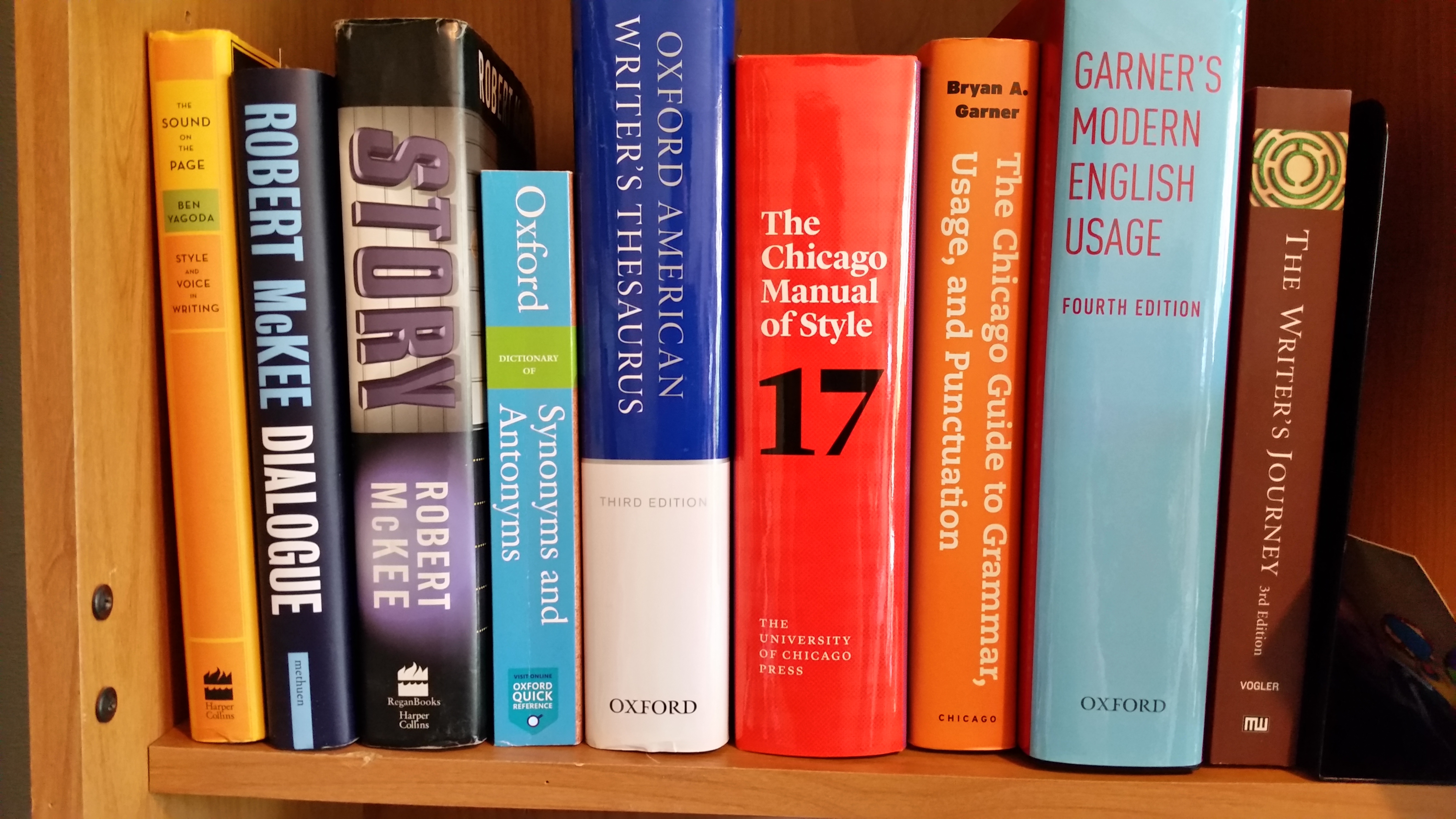

I went out and bought books on the craft of writing, and I am still buying books on the craft today. I will never stop learning and improving.

I went out and bought books on the craft of writing, and I am still buying books on the craft today. I will never stop learning and improving.

Don’t ask a fellow member of a professional writers’ forum to read your work unless you want honest advice. Even if they don’t “get” your work, they will spend their precious time reading it, taking time from their writing to help you out, and that is priceless.

Finally, if you have offered your work to someone who is hypercritical about the small stuff and ignores the structural things you asked them to look at, don’t feel guilty for not asking them to read for you again.

Let it rest for a day or two. Then, look at their comments with a fresh eye and try to see why they made them.

Learning the craft of writing is like learning any other trade, from cooking to carpentry. It takes work and effort to become a master.

Learning the craft of writing is like learning any other trade, from cooking to carpentry. It takes work and effort to become a master.

If you want to craft memorable work, you must own the proper tools for the job and learn how to use them. My “toolbox” contains:

- MS Word as my word-processing program. You may prefer a different program, but this is the one I use.

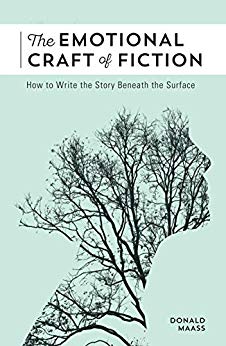

- Books on the craft. Self-education is critical. I refer back to The Chicago Manual of Style and numerous other books on the craft of writing whenever I am stuck. (See a short list of my favorites below.)

- I have trusted, knowledgeable beta-readers for my work and people who give me thoughtful feedback that I can use to make my final draft as good as I can get it.

- I work with a good, well-recommended freelance editor.

- Take free online writing classes.

- Attend conferences and seminars (not free, but worth the money).

- I meet with my weekly writing group.

- I read daily in ALL genres.

One day in 1990, I stumbled upon a book offered in the Science Fiction Book Club catalog: How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy by Orson Scott Card. I’ve said this before, but the day that book arrived in my mailbox changed my life.

That was the day that I stopped feeling guilty for thinking I could be a writer.

The next book I bought was in 2002: On Writing, A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King.

The following is the list of books that are the pillars of my reference library:

- The Chicago Guide to Grammar and Punctuation by Bryan A. Garner.

- The Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms

- Damn Fine Story, by Chuck Wendig

- Dialogue, by Robert McKee

- Steering the Craft: A Twenty-First-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story, by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Story ,by Robert McKee

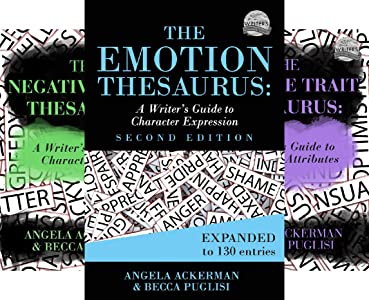

- The Emotion Thesaurus by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi, and I also have all the companion books in that series.

- The Writer’s Journey, by Christopher Vogler

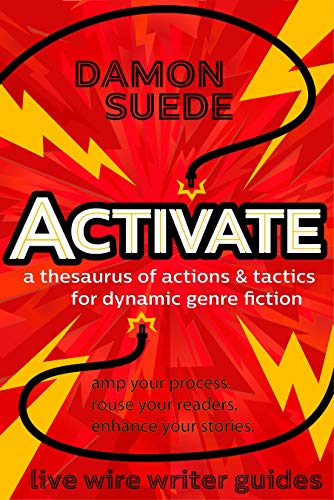

- VERBALIZE by Damon Suede and its companion book, Activate.

Negative feedback is a necessary part of growth. A good, honest critique can hurt if you are only expecting to hear about the brilliance of your work. This is where you have the chance to cross the invisible line between amateur and professional.

We are emotional creatures. When we are just starting on this path, getting an unbiased critique for something you think is the best thing you ever wrote can feel unfair.

We are emotional creatures. When we are just starting on this path, getting an unbiased critique for something you think is the best thing you ever wrote can feel unfair.

I could have embarrassed myself and responded childishly, but that would have been foolish and self-defeating. When I really thought about it, I realized that particular plot twist had been done many times before. I thanked him for his time because I had learned something valuable from that experience.

I could have embarrassed myself and responded childishly, but that would have been foolish and self-defeating. When I really thought about it, I realized that particular plot twist had been done many times before. I thanked him for his time because I had learned something valuable from that experience. Treat all your professional contacts with courtesy, no matter how angry you are. Allow yourself some time to cool off. Don’t have a tantrum and immediately respond with an angst-riddled rant.

Treat all your professional contacts with courtesy, no matter how angry you are. Allow yourself some time to cool off. Don’t have a tantrum and immediately respond with an angst-riddled rant.