Every story is different and requires us to use a unique narrative time. Narrative tense conveys information about time. It relates the time of an event (when) to another time (present, past, or future). So, the narrative tense we choose when writing a particular story indicates its location in time.

In my previous post, we talked about narrative point of view. POV is the perspective, the personal or impersonal “lens” through which we communicate our stories. It is the mode we choose for conveying a particular story.

In my previous post, we talked about narrative point of view. POV is the perspective, the personal or impersonal “lens” through which we communicate our stories. It is the mode we choose for conveying a particular story.

The narrative tense we gravitate to is also a component of our voice.

We shape our stories by combining narrative time with two closely related aspects:

- Narrative point of view.

- Our narrative voice (we’ll explore this more later).

The way that narrative tense affects a reader’s perception of the characters is subtle, an undercurrent that goes unnoticed after the first few paragraphs. It shapes the reader’s view of events on a subliminal level.

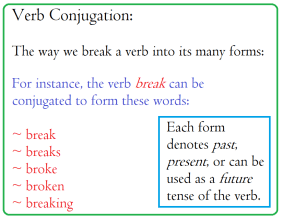

- “I eat.”

- “I am eating.”

- “I have eaten.”

- “I have been eating.”

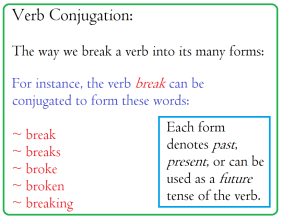

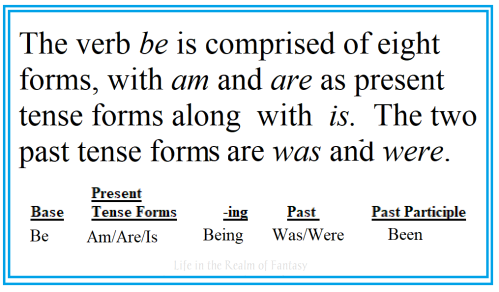

The above sentences are all in the present tense. They contain the present-tense form of a verb: eat, am, and have.

Yet, they are different because each conveys slightly different information, a different point of view about how the act of eating pertains to the present moment.

Revisions are a mess for me because I “think aloud” when writing the first draft. Passive phrasing finds its way into the prose.

When I begin my second draft, those weak verb forms function as traffic signals. They were a form of mental shorthand that helped me write the story before I lost my train of thought. But in the rewrite, weak verbs are code words that tell me what the scene should be rewritten to show.

When I begin my second draft, those weak verb forms function as traffic signals. They were a form of mental shorthand that helped me write the story before I lost my train of thought. But in the rewrite, weak verbs are code words that tell me what the scene should be rewritten to show.

I’ve used these examples before. Each sentence says the same thing, but we get a different story when we change the narrative tense, point of view, and verb choice.

- Henry was hot and thirsty. (Third-person omniscient, past tense, passive phrasing.)

- Henry trudged forward, his lips dry and cracked, yearning for a drop of water. (Third-person omniscient, past tense, active phrasing.)

- I struggle toward the oasis with dry, cracked lips and a parched tongue. (First-person present tense, Active phrasing.)

- You stagger toward the oasis, dizzy with thirst. (Second-person, present tense, active phrasing.)

This is a moment in time for these thirsty characters, and the way we show it to our readers is meaningful in how they perceive the scene.

Sometimes, the only way I can get into a character’s head is to write in the first-person present tense. This is because the narrative time I am trying to convey is the now of that story. (This happens to me most often when writing short stories.)

Every story is unique; some work best in the past tense, while others must be set in the present.

WARNING: When we write a story using an unfamiliar narrative mode, watch for drifting verb tense and wandering narrative point of view.

Drifting verb tense and wandering POV are insidious. Either or both can occur if you habitually write using one mode but switch to another. For this reason, I am vigilant when I begin writing in the first-person present tense, but later discover it isn’t working for me. If I were to switch to close third person past tense, each verb must be changed to match the new narrative mode and time.

But changing an entire draft to a different narrative mode isn’t the only danger zone:

- Time and modes will drift sometimes for no reason other than you were writing as quickly as you could. For this reason, when you begin revisions, it’s crucial to look at your verb forms to ensure your narrative time doesn’t inadvertently drift between past and present.

So, where does voice come into it? An author’s voice is their habit, their fingerprint, a recognizable “sound” in the way a story is communicated.

The way we habitually phrase sentences, how we construct paragraphs, the words we choose, and the narrative mode and time we prefer to write in is our voice. It includes the themes we instinctively write into our work and the ideals we subconsciously hold dear.

The way we habitually phrase sentences, how we construct paragraphs, the words we choose, and the narrative mode and time we prefer to write in is our voice. It includes the themes we instinctively write into our work and the ideals we subconsciously hold dear.

So, our voice (or style) is formed by our deeply held beliefs and attitudes. We may or may not consciously intend to do it. Regardless of intent, our convictions emerge in our writing, leitmotifs that shape character and plot arcs.

As we grow in writing craft and our values and beliefs evolve, that growth is reflected in our voice. We get better at conveying what we intend to say, and our style of writing reflects it.

A fun writing exercise is to write a 100-word short story in a narrative mode that you dislike. Think of it as a little palate cleanser.

Then, rewrite it in that same mode but using a different narrative tense. You might see a wide array of possibilities that a new narrative mode and tense bring to a scene.

If we move to a different window, the view changes. Some views are better than others.

If we move to a different window, the view changes. Some views are better than others. Books like

Books like  Last week, I mentioned head–hopping, a disconcerting literary no-no that occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. I’ve noticed it happens more frequently in third-person omniscient narratives because it’s a mode in which the thoughts of every character are open to the reader.

Last week, I mentioned head–hopping, a disconcerting literary no-no that occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. I’ve noticed it happens more frequently in third-person omniscient narratives because it’s a mode in which the thoughts of every character are open to the reader. I find that when I can’t get a handle on a particular character’s personality, I open a new document and have them tell me their story in the first person.

I find that when I can’t get a handle on a particular character’s personality, I open a new document and have them tell me their story in the first person. Some stories work best with a first-person point of view, while others are too large and require an omniscient narrator.

Some stories work best with a first-person point of view, while others are too large and require an omniscient narrator. Head-hopping occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. It sometimes happens when using a third-person omniscient narrative because each character’s thoughts are open to the author.

Head-hopping occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. It sometimes happens when using a third-person omniscient narrative because each character’s thoughts are open to the author.

One example of a bestseller written in second person POV is

One example of a bestseller written in second person POV is  Today we’re discussing how narrative time, or what we call tense, affects a reader’s perception of character development. In

Today we’re discussing how narrative time, or what we call tense, affects a reader’s perception of character development. In  In the rewrite, we look for the code words that tell us the direction in which we want the narrative to go.

In the rewrite, we look for the code words that tell us the direction in which we want the narrative to go. Sometimes the only way you can get into a character’s head is to write them in the first-person present tense, which happened to me with Thorn Girl. I struggled with her story for nearly six months until a member of my writing group suggested changing the narrative tense and point of view.

Sometimes the only way you can get into a character’s head is to write them in the first-person present tense, which happened to me with Thorn Girl. I struggled with her story for nearly six months until a member of my writing group suggested changing the narrative tense and point of view. Every story is unique, and some work best in the past tense, while others need to be in the present. When we begin writing a story using a narrative time that is unfamiliar to us, we may have trouble with drifting tense and wandering narrative points of view.

Every story is unique, and some work best in the past tense, while others need to be in the present. When we begin writing a story using a narrative time that is unfamiliar to us, we may have trouble with drifting tense and wandering narrative points of view. Today, we’re focusing on the narrative point of view, discussing who can tell the story most effectively, a protagonist, a sidekick, or an unseen witness.

Today, we’re focusing on the narrative point of view, discussing who can tell the story most effectively, a protagonist, a sidekick, or an unseen witness. Some third-person omniscient modes are also classifiable as “third-person subjective,” modes that switch between the thoughts, feelings, etc. of all the characters.

Some third-person omniscient modes are also classifiable as “third-person subjective,” modes that switch between the thoughts, feelings, etc. of all the characters. The flâneur is the nameless external observer, the interested bystander who reports what they see and overhear about a particular person’s story. They garner their information from the sidewalk, window, garden, or any public place where they commonly observe the protagonists. They are an unreliable narrator, as their biases color their observations. In many of the most famous novels told by the flâneur, the reader comes to care about the unnamed narrator because their prejudices and commentary about the protagonists are endearing.

The flâneur is the nameless external observer, the interested bystander who reports what they see and overhear about a particular person’s story. They garner their information from the sidewalk, window, garden, or any public place where they commonly observe the protagonists. They are an unreliable narrator, as their biases color their observations. In many of the most famous novels told by the flâneur, the reader comes to care about the unnamed narrator because their prejudices and commentary about the protagonists are endearing. Second-person point of view is commonly used in guidebooks and self-help books. It’s also common for do-it-yourself manuals, interactive fiction, role-playing games, gamebooks such as the Choose Your Own Adventure series, musical lyrics, and advertisements.

Second-person point of view is commonly used in guidebooks and self-help books. It’s also common for do-it-yourself manuals, interactive fiction, role-playing games, gamebooks such as the Choose Your Own Adventure series, musical lyrics, and advertisements.