Artist: Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

Artist: Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

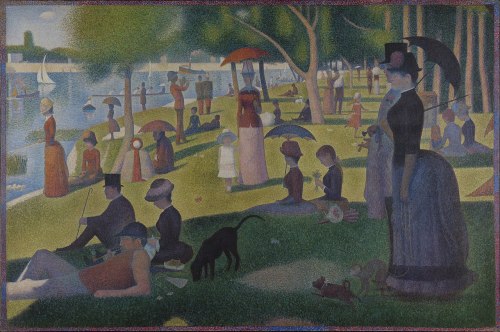

Title: French: Le Louvre, Matin, Printemps (English: the Louvre, morning, spring)

Date:1902

Medium: oil on canvas

Dimensions: height: 54 cm (21.2 in), width: 64.8 cm (25.5 in)

References: https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2023/modern-evening-auction-5/le-louvre-matin-printemps

I first featured this painting last year, when I was desperate for a glimpse of spring. I’m feeling the same wish for color in the gray outdoor world, feeling as if spring can’t come too soon.

What I love about this picture:

This is the way spring begins, tentative and holding back as if gauging the audience before leaping to center stage. The style of brushwork lends itself to the misty quality of the pastels of March and early April.

This was one of Pissarro’s final works. It is a pretty picture, a simple scene not unlike one I might see here in the Pacific Northwest this weekend. We are supposed to see a sunny stretch tomorrow through Tuesday, a few days of warmth without rain. The flowering plum trees in my town are poised to burst forth, and we will take a long drive, soaking up the sunlight while we can.

As I said above, this is a pretty picture, not profound or revolutionary, not highbrow in any way. But sometimes, what the soul needs is a pretty picture featuring the beauty and serenity of a sunny day.

About the artist, via Wikipedia:

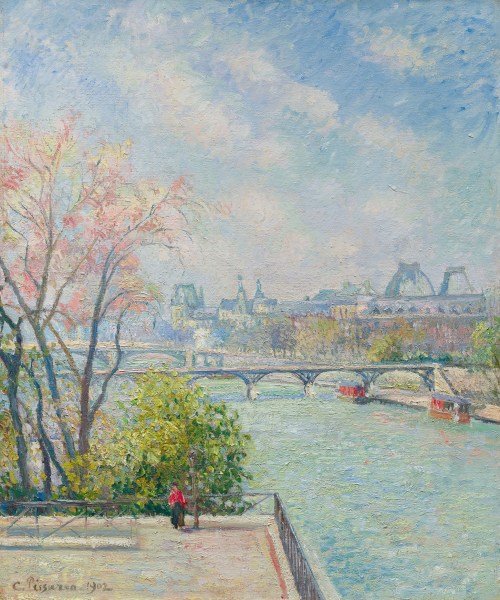

Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro (10 July 1830 – 13 November 1903) was a Danish-French Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist painter born on the island of St Thomas (now in the US Virgin Islands, but then in the Danish West Indies). His importance resides in his contributions to both Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Pissarro studied from great forerunners, including Gustave Courbet and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. He later studied and worked alongside Georges Seurat and Paul Signac when he took on the Neo-Impressionist style at the age of 54.

In 1873 he helped establish a collective society of fifteen aspiring artists, becoming the “pivotal” figure in holding the group together and encouraging the other members. Art historian John Rewald called Pissarro the “dean of the Impressionist painters”, not only because he was the oldest of the group, but also “by virtue of his wisdom and his balanced, kind, and warmhearted personality”. Paul Cézanne said “he was a father for me. A man to consult and a little like the good Lord”, and he was also one of Paul Gauguin‘s masters. Pierre-Auguste Renoir referred to his work as “revolutionary”, through his artistic portrayals of the “common man”, as Pissarro insisted on painting individuals in natural settings without “artifice or grandeur”.

Pissarro is the only artist to have shown his work at all eight Paris Impressionist exhibitions, from 1874 to 1886. He “acted as a father figure not only to the Impressionists” but to all four of the major Post-Impressionists, Cézanne, Seurat, Gauguin, and van Gogh.

Founder of a Dynasty:

Camille’s son Lucien was an Impressionist and Neo-impressionist painter as were his second and third sons Georges Henri Manzana Pissarro and Félix Pissarro. Lucien’s daughter Orovida Pissarro was also a painter. Camille’s great-grandson, Joachim Pissarro, became Head Curator of Drawing and Painting at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and a professor in Hunter College’s Art Department. Camille’s great-granddaughter, Lélia Pissarro, has had her work exhibited alongside her great-grandfather. Another great-granddaughter, Julia Pissarro, a Barnard College graduate, is also active in the art scene. From the only daughter of Camille, Jeanne Pissarro, other painters include Henri Bonin-Pissarro (1918–2003) and Claude Bonin-Pissarro (born 1921), who is the father of the Abstract artist Frédéric Bonin-Pissarro (born 1964).

The grandson of Camille Pissarro, Hugues Claude Pissarro (dit Pomié), was born in 1935 in the western section of Paris, Neuilly-sur-Seine, and began to draw and paint as a young child under his father’s tutelage. During his adolescence and early twenties he studied the works of the great masters at the Louvre. His work has been featured in exhibitions in Europe and the United States, and he was commissioned by the White House in 1959 to paint a portrait of U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower. He now lives and paints in Donegal, Ireland, with his wife Corinne also an accomplished artist and their children. [1]

Credits and Attributions:

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:1902 Camille Pissarro Le Louvre, matin, printemps.jpeg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:1902_Camille_Pissarro_Le_Louvre,_matin,_printemps.jpeg&oldid=948378278 (accessed March 7, 2025).

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Camille Pissarro,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Camille_Pissarro&oldid=1278793537 (accessed March 7, 2025).

Artist: Georges Seurat (1859–1891)

Artist: Georges Seurat (1859–1891)