We are still working on the second draft of our manuscript. We have searched for our code words and examined our character arcs for agency and consequences.

The Second Draft: Decoding My Mental Shorthand #writing

The Second Draft: agency and consequences #writing

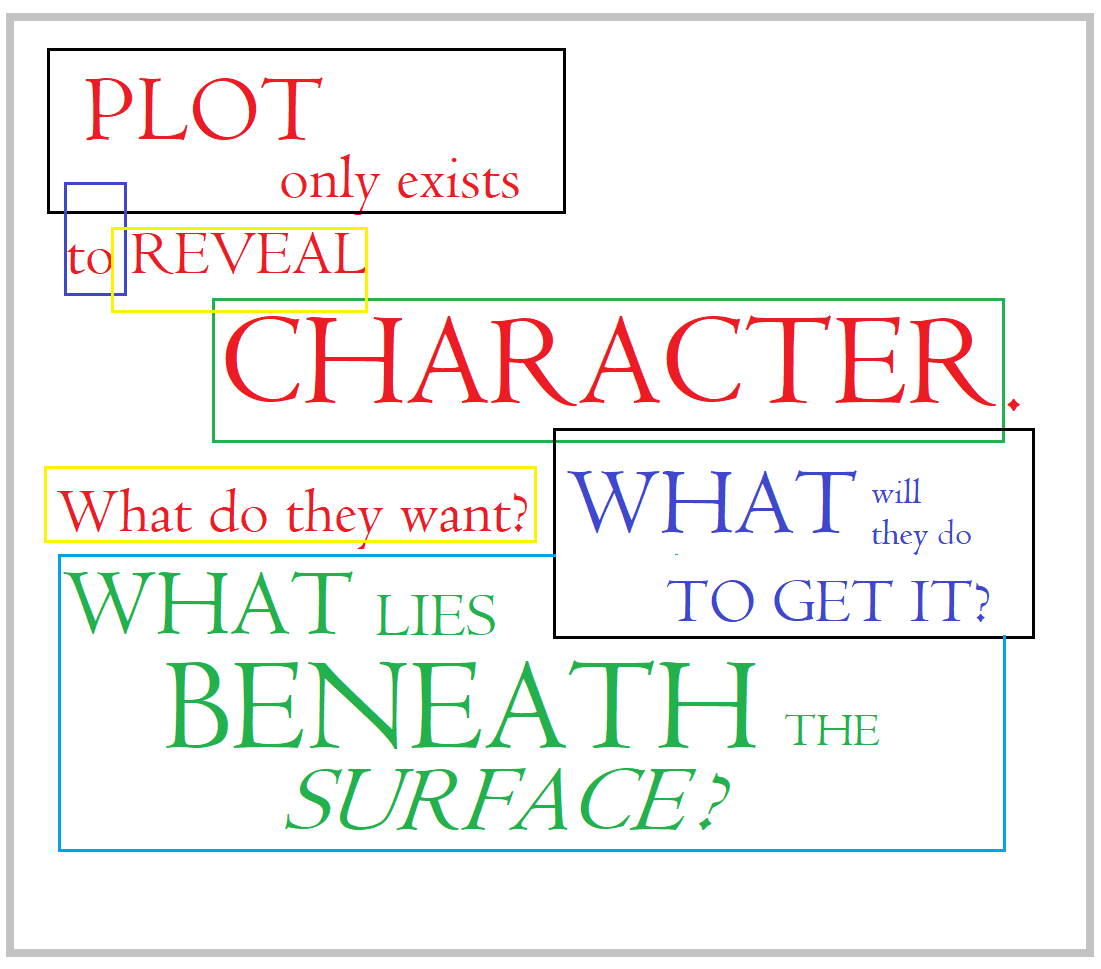

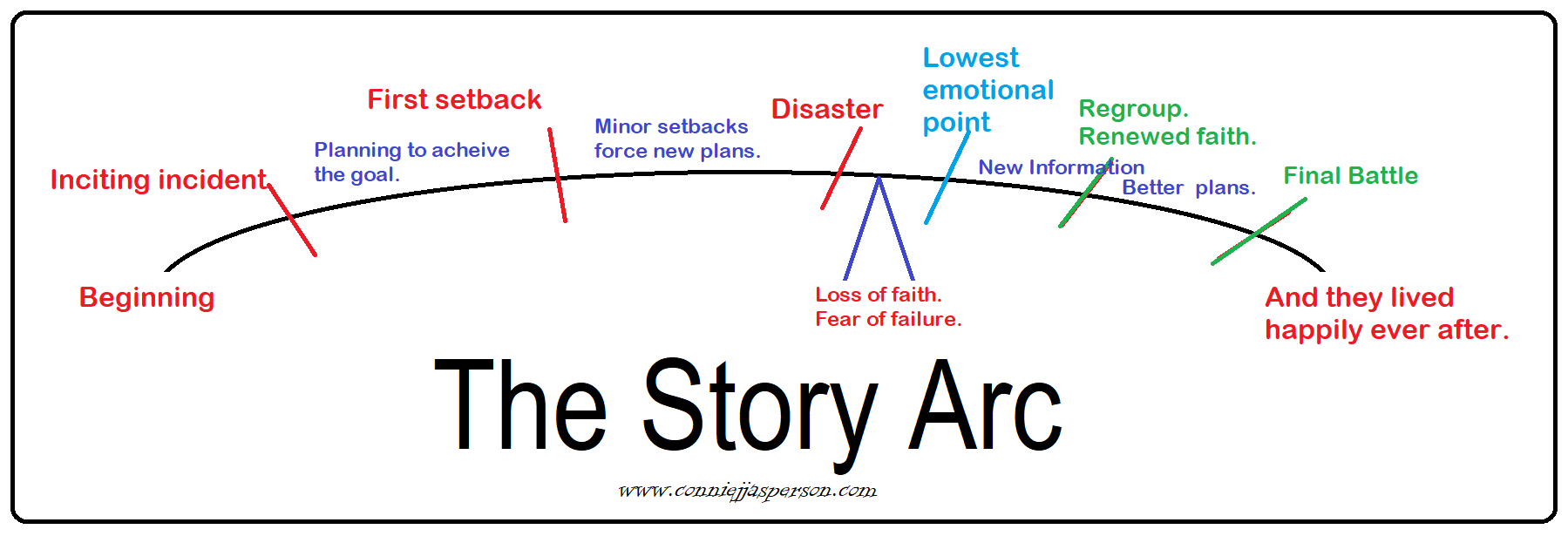

Today, we’re looking at the arc of the plot. This is a good opportunity to open a new document and answer a few questions about your story. The list of questions and their answers will inform you of the areas that need more work before you send the manuscript to a beta reader.

Today, we’re looking at the arc of the plot. This is a good opportunity to open a new document and answer a few questions about your story. The list of questions and their answers will inform you of the areas that need more work before you send the manuscript to a beta reader.

First, let’s take a second look at the overarching objective. This is the reason the story exists, and we made a stab at identifying it in the first draft. But now we want to make that problem clear.

- Is the quest worthy of a story? What does the hero need, and would they risk everything to acquire it?

- Have we shown how badly they want it and, most importantly, why they are so desperate for it?

- Why do they feel entitled to it?

- How far are they willing to go to acquire it?

Second, we examine the antagonist. Have we shown the opposition as clearly as we have the protagonist? The whole story hinges on whether or not our protagonist faces a real threat. A weak enemy is no threat at all, so

Who is the antagonist?

Who is the antagonist?- Do they have a personality that shows them as rounded and multidimensional rather than as a two-dimensional cartoon villain?

- Do they change and evolve as a person throughout the story, for good or for evil? A character arc must encompass several stages of personal growth. What those stages are is up to you and depends on the story you are telling.

- What do they want?

- Why do they feel entitled to it?

- How far are they willing to go to get it?

Third, how convincing is the inciting incident? I learned this the hard way—long lead-ins don’t hook the reader. Long lead-ins offer too much opportunity for the inclusion of insidious info dumps.

- Whether we show it in the prologue or the opening chapter, the first event, the inciting incident, changes everything and launches the story. The universe that is our story begins expanding at that moment.

- The first incident has a domino effect. More events occur, pushing the protagonist out of his comfortable life and into danger. Fear of death, fear of loss, fear of financial disaster, fear of losing a loved one—terror is subjective and deeply personal.

- The threat and looming disaster must be made clear to the reader at the outset. Nebulous threats mean nothing in real life, although they cause a lot of subconscious stress.

- Those vague threats might be the harbinger of what is to come in a book, but they only work if the danger materializes quickly and the roadblocks to happiness soon become apparent.

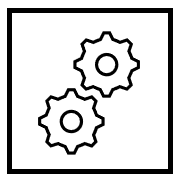

Fourth, let’s look at logic and the pinch points. Pinch points (events that threaten the quest) are the cogs that keep the wheels of your story turning. How strong are the pinch points in this story?

- Was this failure the logical outcome of the characters’ decisions? Or does this event feel random, like spaghetti tossed at a wall to see what sticks?

- Does the first pinch point feel strong enough to hook a reader?

The internet says that pinch points frequently occur between moving objects or parts of a machine.

Consider cogs: they are engineered to interlock with each other, and when they move close enough that one cog interlocks and turns another, they move other parts of the mechanism.

Consider cogs: they are engineered to interlock with each other, and when they move close enough that one cog interlocks and turns another, they move other parts of the mechanism.

When a machine is powered by mechanical or electrical means, the places where the cogs meet other cogs or other parts of the machinery are the danger zones, the places where people can be injured or even killed.

So, our narrative is our machine, and the events (pinch points) are the cogs that move it along.

Logic is the oil that keeps our gears turning.

Fifth: midpoint: What are the circumstances in which we find each character at the midpoint?

From the midpoint to the final plot point, pacing is critical, and the reader must be able to see how the positive and negative consequences affect the emotions of ALL the characters. We must show their emotional and physical condition and the circumstances in which they now find themselves.

The antagonist will be pleased, perhaps elated.

The protagonist will be worried, perhaps depressed.

- Did we fully explore how the events emotionally destroy them?

- Did we shed enough light on how their personal weaknesses are responsible for the bad outcome?

- Did we show how this failure causes the protagonist to question everything they once believed in?

- Did we offer them hope? What did we offer them that gave them the courage to persevere and face the final battle?

- Finally, did we explore how this emotional death and rebirth event makes them stronger?

Each hiccup on the road to glory must tear the heroes down. Events and failures must break them emotionally and physically so that in the book’s final quarter, they can be rebuilt, stronger, and ready to face the enemy on equal terms.

Each hiccup on the road to glory must tear the heroes down. Events and failures must break them emotionally and physically so that in the book’s final quarter, they can be rebuilt, stronger, and ready to face the enemy on equal terms.

Why does the antagonist have the upper hand? What happens at the midpoint to change everything for the worse?

Sixth: we look closely at the last act, which is the final quarter of the story.

- At the ¾ point, your protagonist and antagonist should have gathered their resources and companions.

- Each should believe they are as ready to face each other as they can be under the circumstances.

The final pages of the story are the reader’s reward for sticking with it to that point.

- Did we hold the solution just out of reach for the first ¾ of the narrative? Did we lure the reader to stay with us by giving them the promise of a solution?

- Did we show clearly that every time our characters nearly resolved their situation, they didn’t, and things got worse?

- Did we bring the protagonist and antagonist together for a face-to-face meeting?

- Was that meeting an epic conflict that deserved to be included in that story?

- Did that meeting bring the story to a solid conclusion?

- How well did we choreograph that final meeting?

Confrontations are chaotic. It’s our job to control that chaos and create a narrative with an ending that is as intense as our imaginations and logic can make it.

Confrontations are chaotic. It’s our job to control that chaos and create a narrative with an ending that is as intense as our imaginations and logic can make it.

Once we have examined the plot arc and are satisfied with its outcome, we may think it’s ready for a beta reader.

But it might not be, as we still have a few steps to complete. The beta reader’s comments will inform how we approach our third draft, so we want the manuscript we give them to be as free of easily resolved bloopers and distractions as possible. That way they will be better able to see the strengths of the story as well as the weaknesses.

Next week, we’ll examine the next steps to making a manuscript ready for a trusted beta reader. I’ll also discuss how I find readers who can accept that my story still has flaws and who understand what I am asking them to look for.