As an editor, I saw every kind of mistake you can imagine, and before that, as a writer, I made them all. This is why I rely on an editor for my work. Irene sees the flaws that my eye skips over.

When prepping a novel to send to Irene, I use a three-part method. This requires specific tools that come with Microsoft Word, my word-processing program. I believe these tools are available for Google Docs and every other word-processing program. Unfortunately, I am only familiar with Microsoft’s products as they are what the companies that I worked for used.

When prepping a novel to send to Irene, I use a three-part method. This requires specific tools that come with Microsoft Word, my word-processing program. I believe these tools are available for Google Docs and every other word-processing program. Unfortunately, I am only familiar with Microsoft’s products as they are what the companies that I worked for used.

What follows are three steps that should eliminate most problems in a manuscript.

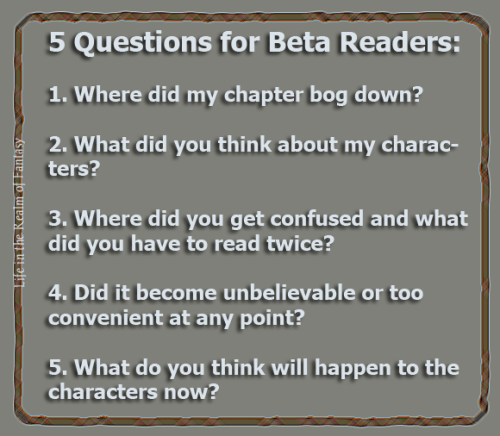

Part one: Beta Reading is the first look at a manuscript by someone other than the author. I suggest you don’t omit this step unless you can find no one who understands what you need. A good beta reader is a person who reads for pleasure and can gently express what they think about a story or novel. Also, look for a person who enjoys the genre of that particular story. Your beta reader should ask several questions of this first draft (feel free to give them the following list).

Part two: Once I have ironed out the rough spots noticed by my beta readers, this second stage is put into action. Yes, on the surface the manuscript looks finished, but it has only just begun the journey.

Part two: Once I have ironed out the rough spots noticed by my beta readers, this second stage is put into action. Yes, on the surface the manuscript looks finished, but it has only just begun the journey.

In Microsoft Word, on the Review Tab, I access the Read Aloud function and begin reading along with the mechanical voice. Yes, the narrator app is annoying and mispronounces words like “read,” which sound different and have different meanings depending on the context. However, this first tool alerts me to areas that were overlooked in the first stage of revisions.

The most frustrating part is the continual stopping, making corrections, and starting.

The most frustrating part is the continual stopping, making corrections, and starting.

I use this function rather than reading it aloud from the monitor, as the computer screen tricks the eye. I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is.

- I habitually key the word though when I mean through or lighting when I mean lightning. Each is a different word but is only one letter apart. Most (but not all} miss keyed words will leap out when you hear them read aloud.

- Most but not all run-on sentences stand out when you hear them read aloud.

- Most but not all inadvertent repetitions also stand out.

- Most of the time, hokey phrasing doesn’t sound as good as you thought it was.

- Most of the time, you hear where you have dropped words because you were keying so fast you skipped over including an article, like “the” or “a” before a noun.

This is a long process that involves a lot of stopping and starting. It takes me well over a week to get through an entire 90,000-word manuscript. I will have trimmed about 3,000 words by the end of this phase. I will have caught many typos and miss keyed words and rewritten many clumsy passages.

But I am not done.

Part three: the manual edit. This is where I make a physical copy and do the work the old-fashioned way.

Everything looks different when printed out, and you will see many things you don’t notice on the computer screen or hear when it is read aloud by the narrator app.

-

Illustration by Hugh Thomson representing Mr. Collins protesting that he never reads novels.

Open your manuscript. Make sure the pages are numbered in the upper right-hand corner.

- Print out the first chapter and either staple it together or use a binder clip. If I drop it, the pages will all be together in the proper order.

- Turn to the last page. Cover the page with another sheet of paper, leaving only the final paragraph visible.

- Starting with the final paragraph on the last page, begin reading, working your way forward.

- With a yellow highlighter, mark each place that needs revising.

- With a red pen/pencil, make notes in the margins to guide the revisions. (Red is highly visible, so you won’t miss it when you are putting your corrections into the digital manuscript.

- Put the corrected chapter on a recipe stand next to your computer. Open your manuscript and save it as a new file. (ManuscriptTitle_final_Apr2024.docx.) Begin making the revisions as noted on your hard copy.

- Do the same for each chapter until you have finished revising the entire manuscript.

I look for info dumps, passive phrasing, and timid words. They are signs that a section needs rewriting to make it visual rather than telling. Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals telling me what I intend that scene to be. Many times, I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination.

I will have trimmed another 3 to 4,000 more words from my manuscript by the end of this process.

By the time we begin writing, most of us have forgotten whatever grammar we once knew. But editing software operates on algorithms and doesn’t understand context.

I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. Look at each thing they point out and decide whether to accept their recommendation or not. They are AI programs and have no real-life experience to draw on.

I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. Look at each thing they point out and decide whether to accept their recommendation or not. They are AI programs and have no real-life experience to draw on.

You’ll get into trouble if you assume the AI editing programs are always correct. Remember, they don’t understand context. Good writing involves technical knowledge of grammar, but voice isn’t about algorithms.

Novels are comprised of many essential components. If one element fails, the story won’t work the way I envision it. It’s been months since a beta reader saw this mess and much has changed. I take a hard look at these aspects:

- Characterization – are the characters individuals?

- Dialogue – do people sound natural? Do they sound alike, or are they each unique?

- Mechanics (grammar/punctuation flaws will be more noticeable when printed out)

- Pacing—how does it transition from action scene to action scene?

- Plot – does the story revolve around a genuine problem?

- Prose – how do my sentences flow? Do they say what I mean?

- Themes – What underlying thread ties the whole story together? Have I used the theme to its best potential?

Being a linear thinker, this process of making revisions works for me. It can take more than a month, but when I’ve finished, I’ll have a manuscript that won’t be full of avoidable distractions. It will be something I can send to my editor. And because I have done my best work, Irene will be able to focus on finding as much of what I have missed as is humanly possible.

If you read as much as I do (and this includes books published by large Traditional publishers), you know that a few mistakes and typos can and will get through despite their careful editing. So, don’t agonize over what you might have missed. If you’re an indie, you can upload a corrected file.

If you read as much as I do (and this includes books published by large Traditional publishers), you know that a few mistakes and typos can and will get through despite their careful editing. So, don’t agonize over what you might have missed. If you’re an indie, you can upload a corrected file.

We are all only human, after all.