We have been working on plotting a novel for the last month in our series, Idea to Story. The previous installments are listed below, but at this point, we have our two main characters, Val (Valentine), a lady knight, and the enemy, Kai Voss, a court sorcerer. Both are regents for the sickly, underage king.

We also have our ultimate enemy, Donovan Dove, Kai’s half-brother and most trusted advisor. I have landed on a working title that speaks to the genre, Valentine’s Gambit.

We also have our ultimate enemy, Donovan Dove, Kai’s half-brother and most trusted advisor. I have landed on a working title that speaks to the genre, Valentine’s Gambit.

We have allowed the characters to tell us the story. Save everything you cut to a new document, labeled and dated: “Outtakes_ValentinesGambit_03-08-25.” (That stands for Outtakes, Valentine’s Gambit, March 2025.)

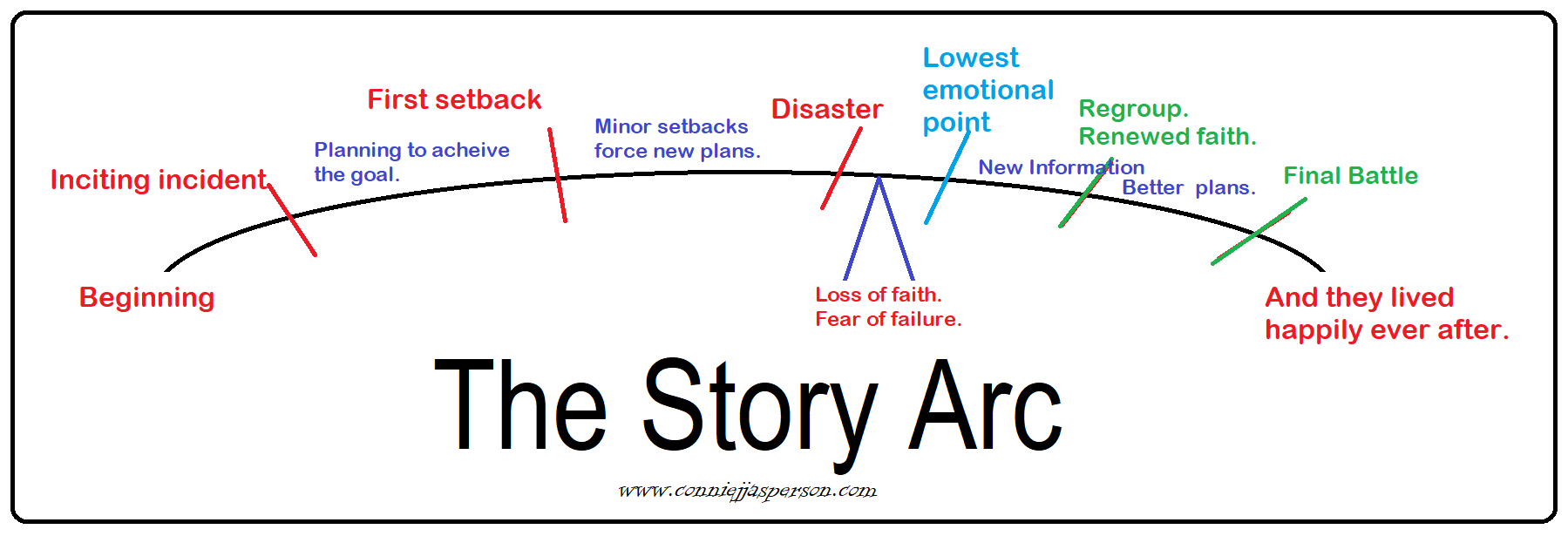

The Inciting Incident: The plot as it stood last week: Twelve-year-old Edward has been steadily declining in health since the deaths of his parents. Information has come to Val’s attention that someone highly trusted has cursed the young king with a wasting illness. She immediately suspects Kai and moves Edward to a safe place. The story is off and running.

Kai has also received information from his most trusted source that Edward is being poisoned. His suspicions immediately fall on Val, whom he believes wishes to take the throne and rule as a warrior queen. When he discovers the king has been taken from the castle (kidnapped, as he believes), he rallies the soldiers loyal to him and mounts a search.

Roadblocks arise as Val and her soldiers hinder Kai’s attempts to regain custody of Edward. Kai finds a way around them, leading to another crisis scene and a stalemate.

At the Midpoint, Donovan Dove springs his trap, capturing both Kai and Valentine and imprisoning them in his dungeon. He posts announcements in all the towns proclaiming that they are traitors who have tried to kill the young king. He assumes the role of regent and plans to behead them at dawn.

Val immediately comprehends what just happened and finds a way to escape. Against her better judgment, she makes a spur-of-the-moment decision to free Kai, dragging him to her grandmother’s house. Only now is the mage discovering the magnitude of his brother’s betrayal.

Val immediately comprehends what just happened and finds a way to escape. Against her better judgment, she makes a spur-of-the-moment decision to free Kai, dragging him to her grandmother’s house. Only now is the mage discovering the magnitude of his brother’s betrayal.

This dungeon scene tells the reader that our true quest will be rescuing Edward before he dies from Donovan’s curse.

Now, we must consider the best way to end this mess. Something big and important must be achieved in the final chapters.

First, Val and Kai have to stop blaming each other and agree to work together.

- Val’s grandmother has some tough love for both of them.

Second, they must gather a core group of talented people. Donovan has murdered the friends he used as messengers in his betrayal, but several other friends of each are in hiding. So, Val and Kai must leave her grandmother’s hut and rally their supporters.

They need a thief/spy and two soldiers, and Val knows where to find them. They also need a healer because Edward is near death. Val’s grandmother could fill that role—she is already named and her abilities are established.

- They can build up an army if you choose, but limiting the number of named characters is crucial.

Third, they need a base, a place to live, and resources to gather while they devise the plan to free Edward. Grandmother’s hut is known to Donovan’s minions so they must move on.

What is the core conflict? For me, a good way to find the ending is to revisit the notes I have made as the story evolves. If I have been on top of things, each change has been noted, so I’m looking at the current blueprint of the novel to this point.

This is when I go back to square one. By seeing the whole picture of the story to this point, I usually find the inspiration to put together the final scenes that I know must happen. I sit down with a notebook (or, in my case, a spreadsheet) and make a list of what events must occur between the place where they escape the dungeon and the end. I save that document with a title, something like:

This is when I go back to square one. By seeing the whole picture of the story to this point, I usually find the inspiration to put together the final scenes that I know must happen. I sit down with a notebook (or, in my case, a spreadsheet) and make a list of what events must occur between the place where they escape the dungeon and the end. I save that document with a title, something like:

Valentines_Gambit _Final_Chpts_Worksheet_03-08-2025

At first, the page is only a list. The chapter headings are pulled out of the ether, accompanied by the howling of demons as I force my plot to take shape:

- Chapter – Val drags Kai to a safe place. Discovery of the deaths of close friends.

- Chapter – Donovan’s plan revealed.

- Chapter – Evading Donovan’s bespelled soldiers.

- Chapter – Discovering where Edward is being held

- (and so on until the last event) Mage duel – ends when Kai casts a beginner’s spell to trip Donovan, and Val kills him.

- Final chapter – Val and Kai reinstated as regents. Together they raise Edward to adulthood and he grows up to be a good, beloved king, Will they marry? It’s a romance, so yes, they will live as happily as people ever do.

I begin writing details that pertain to the section beneath each chapter heading as they occur to me. Once that list is complete, those sketchy details get expanded on and grow into complete chapters, which I then copy and paste into the manuscript.

![]() So, let’s talk about the elephant in the room – what to do with scenes that no longer work now that we’re nearing the end. Something we all suffer from is the irrational notion that “if we wrote it, we have to keep it,” even though it no longer fits.

So, let’s talk about the elephant in the room – what to do with scenes that no longer work now that we’re nearing the end. Something we all suffer from is the irrational notion that “if we wrote it, we have to keep it,” even though it no longer fits.

Let’s be honest. No amount of rewriting and adjusting will make a scene or chapter work if it’s no longer needed to advance the story. If the story is stronger without that great episode, cut it.

What you have written but not used in the finished novel is a form of world-building. It contributes to the established canon of that world and makes it more real in your mind. I urge you to save your outtakes with a file name that clearly labels them as background or outtakes. Not having to reinvent those useful sections will significantly speed up other projects.

Use the outtakes as fodder for a short story or novella set in that world. This is how prolific authors end up with so many short stories to make into compilations. It’s useful to know that with a few name changes, every side quest not used in the final manuscript can quickly be made into a short story.

Another good reason to save everything you cut in a separate document is this: I often reuse some of that prose later, at a place where it makes more sense.

Another good reason to save everything you cut in a separate document is this: I often reuse some of that prose later, at a place where it makes more sense.

That need to cut and rearrange is why I don’t number my chapters in the first draft. You may have noticed in the example above that I head each section with the word “chapter” (and no number) written out. I want to be able to find the word “chapter” with a global search when I do insert the numbers.

This is because (in my world) most first drafts are not written linearly. For me, the story arc changes structurally as I lay down that first draft, so chapter numbers become confusing. Nowadays, I put the numbers in when the manuscript has made it through the final draft and is ready for my editor.

Designing the ending is as challenging (and yet easy) as writing the opening scenes. It is so satisfying to write those final pages—one of the best feelings I have experienced as an author.

The sample plot that we have used for this series has a happy ending. This is because within the first five chapters, when we began writing our characters, it became a Romantasy and romance readers want happy endings.

Sometimes, we all want happy endings.

PREVIOUS IN THIS SERIES:

Idea to story part 2: thinking out loud #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 3: plotting out loud #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 4 – the roles of side characters #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 5 – plotting treason #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

In literary terms, this uneven distribution of knowledge is called asymmetric information. We see this all the time in the corporate world.

In literary terms, this uneven distribution of knowledge is called asymmetric information. We see this all the time in the corporate world. Jared is hilarious, charming, naïve, a bit cocky, and completely unaware that he’s an arrogant jackass. He is a young man who is exceptionally good at everything and is happy to tell you about it. Jared has no clue that his boasting holds him back, as no one wants to work with him.

Jared is hilarious, charming, naïve, a bit cocky, and completely unaware that he’s an arrogant jackass. He is a young man who is exceptionally good at everything and is happy to tell you about it. Jared has no clue that his boasting holds him back, as no one wants to work with him. When I started writing this story, I had the core conflict: Jared’s misguided desire to be important. I had the surface quest: rescuing the kidnapped kid. I had the true quest: Jared learning to laugh at himself and developing a little humility.

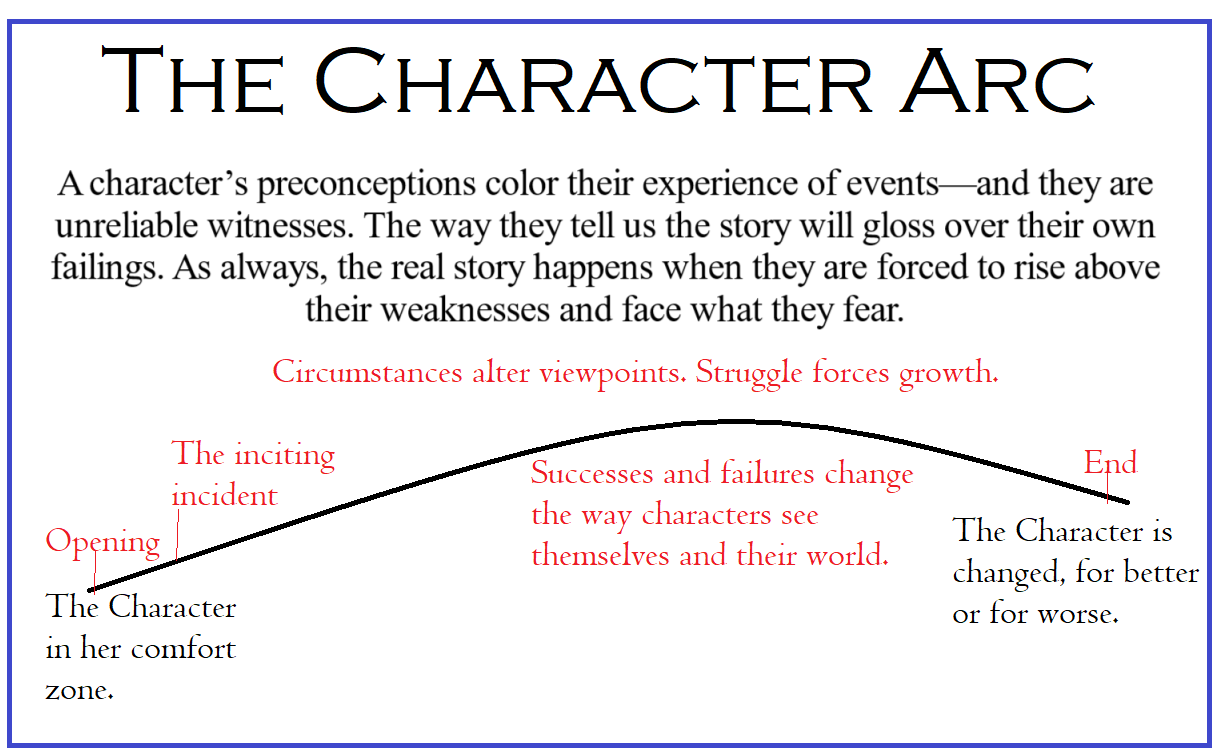

When I started writing this story, I had the core conflict: Jared’s misguided desire to be important. I had the surface quest: rescuing the kidnapped kid. I had the true quest: Jared learning to laugh at himself and developing a little humility. Now we’re going to design the conflict by creating a skeleton, a series of guideposts to write to. I write fantasy, but every story is the same, no matter the set dressing: Protagonist A needs something desperately, and Antagonist B stands in their way.

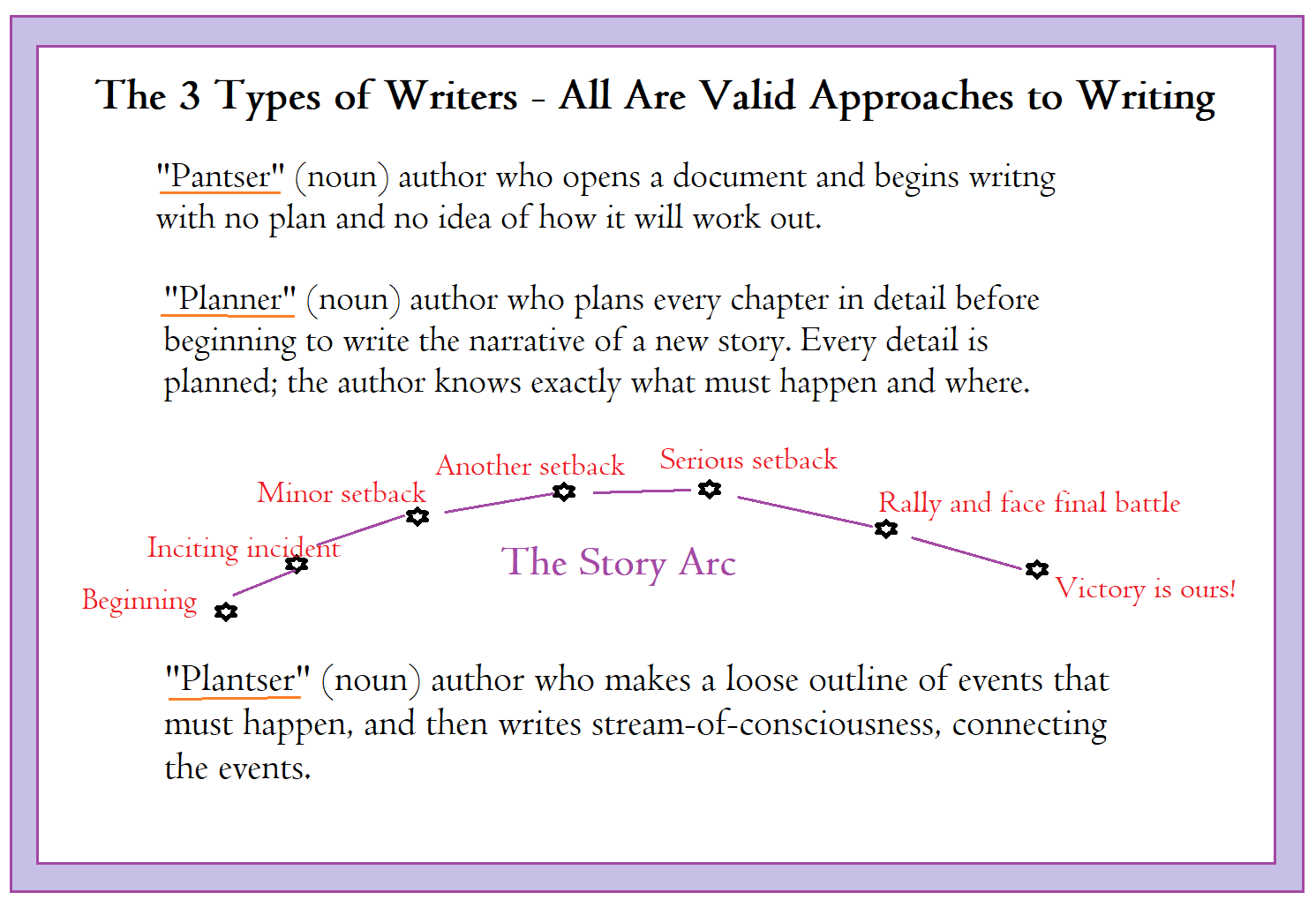

Now we’re going to design the conflict by creating a skeleton, a series of guideposts to write to. I write fantasy, but every story is the same, no matter the set dressing: Protagonist A needs something desperately, and Antagonist B stands in their way. Where does our soldier’s story begin? We open the story by introducing our characters, showing them in their everyday world, and then we kick into gear with the occurrence of the “inciting incident,” which is the first plot point. That might be their arrival at their first camp in the Ardennes region.

Where does our soldier’s story begin? We open the story by introducing our characters, showing them in their everyday world, and then we kick into gear with the occurrence of the “inciting incident,” which is the first plot point. That might be their arrival at their first camp in the Ardennes region.

One thing that I do is make notes that help limit my tendency toward heavy-handed foreshadowing. I try to keep it brief, but what will be enough of a hint, and where should it go?

One thing that I do is make notes that help limit my tendency toward heavy-handed foreshadowing. I try to keep it brief, but what will be enough of a hint, and where should it go?