Thoughts on “A Christmas Carol” was first published here on Life in the Realm of Fantasy, Dec. 15, 2014 under the title, A Christmas Carol–what I’ve learned from Charles Dickens. Because I adore the works of Charles Dickens, and especially love A Christmas Carol, I reprint this article every year during the week before Christmas. It has become my little Christmas card to you and to the world.

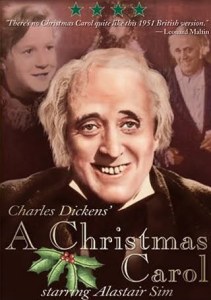

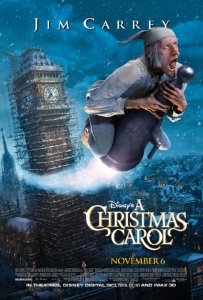

![John Leech [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/marleys_ghost_-_a_christmas_carol_1843_opposite_25_-_bl.jpg?w=216&h=300) Charles Dickens was a master at creating marvelous hooks and using heavy foreshadowing. Let’s take the first line of my favorite Christmas story of all time, A Christmas Carol. I love each and every version of it, will watch any movie version I can get my hands on:

Charles Dickens was a master at creating marvelous hooks and using heavy foreshadowing. Let’s take the first line of my favorite Christmas story of all time, A Christmas Carol. I love each and every version of it, will watch any movie version I can get my hands on:

“Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.”

I hear a great deal of argument about how modern 21st century genre-fiction is nothing but sixty-second soundbites and bursts of action jammed together in dumbed-down prose. I hate to say this, but that has been true of popular fiction for centuries–and if you look at this tale, you will see what I mean. The popular prose, at the time it was written, was more descriptive and leisurely than we enjoy nowadays, but even so, the popular tales leaped straight to the action.

In that first paragraph, Dickens tosses out the bait, sinking the hook, and landing the fish (the reader) by foreshadowing the first plot point of the story–the visitation by Marley’s ghost. We want to know why Marley’s definite state of decay was so important that the conversation between you the reader, and Dickens, the author, was launched with that topic.

He picks it up and does it again several pages later, with the little scene involving the door-knocker:

“Now, it is a fact, that there was nothing at all particular about the knocker on the door, except that it was very large. It is also a fact, that Scrooge had seen it, night and morning, during his whole residence in that place; also that Scrooge had as little of what is called fancy about him as any man in the city of London, even including — which is a bold word — the corporation, aldermen, and livery. Let it also be borne in mind that Scrooge had not bestowed one thought on Marley, since his last mention of his seven years’ dead partner that afternoon. And then let any man explain to me, if he can, how it happened that Scrooge, having his key in the lock of the door, saw in the knocker, without its undergoing any intermediate process of change — not a knocker, but Marley’s face.

“Marley’s face. It was not in impenetrable shadow as the other objects in the yard were, but had a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar. It was not angry or ferocious, but looked at Scrooge as Marley used to look: with ghostly spectacles turned up on its ghostly forehead. The hair was curiously stirred, as if by breath or hot air; and, though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. That, and its livid colour, made it horrible; but its horror seemed to be in spite of the face and beyond its control, rather than a part or its own expression.

“As Scrooge looked fixedly at this phenomenon, it was a knocker again.”

You must admit, it’s a huge thing for a man of as limited an imagination as Scrooge was known to have, to suddenly see his dead friend staring back at him.

This is also the second foreshadowing of the events that will follow and makes the reader want to know what will happen next.

At this point, we’ve followed Scrooge through several scenes introducing the subplots. We have met the man who, at this point, is named only as ‘the clerk’ in the original manuscript, but whom we will later know to be Bob Cratchit, and we’ve met Scrooge’s nephew, Fred. These two subplots are critical, as our man Scrooge’s redemption revolves around the ultimate resolution of these disparate mini-stories—he must witness the joy and love in Cratchit’s family, who are suffering but happy despite the grinding poverty for which Scrooge bears responsibility.

We see that his nephew, Fred, though orphaned is well enough off in his own right, but craves a relationship with his uncle with no thought or care of what he might gain from it financially.

All the characters are in place. We’ve seen the city, cold and dark, with danger lurking in the shadows. We’ve observed the way Scrooge interacts with everyone around him, strangers and acquaintances alike.

Now we come to the first plot point–Marley’s visitation. This is where the set-up ends, and the story takes off.

Dickens raises the tension. The bells begin ringing for no apparent reason and “The cellar-door flew open with a booming sound, and then he heard the noise much louder, on the floors below; then coming up the stairs; then coming straight towards his door.

Scrooge, of course, is dismayed and tries to deny the strange happenings. He desperately clings to his view of reality.

“It’s humbug still!” said Scrooge. “I won’t believe it.”

However, he can’t deny this phenomenon forever and refusing to recognize it won’t make it go away.

“Though he looked the phantom through and through, and saw it standing before him; though he felt the chilling influence of its death-cold eyes; and marked the very texture of the folded kerchief bound about its head and chin, which wrapper he had not observed before: he was still incredulous, and fought against his senses.

“How now!” said Scrooge, caustic and cold as ever. “What do you want with me?”

![John Leech [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/scrooges_third_visitor-john_leech1843.jpg?w=187&h=300) This is the turning point, the place where Ebenezer Scrooge is faced with a situation in which he will either succeed or fail and what will happen to him, the reader can’t guess. A deep sense of mystery now surrounds this miserly old man–what could possibly be so important about him that a man he cared so little for in life would go to such trouble as to return from the grave to save him?

This is the turning point, the place where Ebenezer Scrooge is faced with a situation in which he will either succeed or fail and what will happen to him, the reader can’t guess. A deep sense of mystery now surrounds this miserly old man–what could possibly be so important about him that a man he cared so little for in life would go to such trouble as to return from the grave to save him?

In 1843 Charles Dickens showed us how to write a compelling tale that would last for generations. We start with the hook, use foreshadowing, introduce the subplots that ultimately support the structure of the tale, and arrive at the first plot point–these are the things that make up the first quarter of this timeless tale. Get these properly in line, and your story will intrigue the reader, involving them to the point they don’t want to set the book down.

Credits and Attributions:

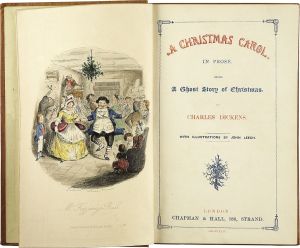

Passages quoted from A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, by Charles Dickens, With Illustrations by John Leech. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843. First edition. PD|100

Marley’s Ghost, and Scrooge’s third visitor. These images are two of four hand-coloured etchings included in the first edition. There were also four black and white engravings. Date1843. PD|100. John Leech [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Merry Christmas to you and to your loved ones from me, and my favorite author, Charles Dickens!