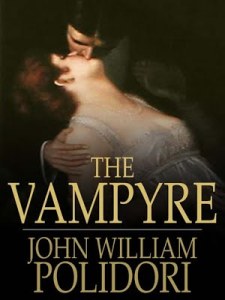

Artist: Jakub Schikaneder (1855–1924)

Artist: Jakub Schikaneder (1855–1924)

Title: Evening Street

Date: 1906

Medium: oil on canvas

Inscriptions: signed and dated

Collection: National Gallery Prague

About this Painting, via Copilot GPT (sources listed in the footnotes below):

Evening Street by Jakub Schikaneder is done in the Romanticism style, characterized by its blend of realism and melancholy. In this enchanting cityscape, Schikaneder masterfully captures the quietude of an evening street in Prague. The scene exudes a sense of solitude and nostalgia, as if time has slowed down. The play of light and shadow adds depth to the composition, emphasizing the architectural details and the cobblestone pavement.

The painting invites us to wander through the narrow streets, perhaps imagining the footsteps of passersby and the whispers of history. The subdued palette, with hints of warm tones, evokes the fading light of day. It’s a moment frozen in time—a glimpse into the soul of the city.

Schikaneder often depicted lower-class people in his works, and Evening Street is no exception. The figures, though not prominent, contribute to the overall atmosphere. Their silhouettes blend seamlessly with the surroundings, emphasizing the quiet beauty of everyday life. [1]

About the Artist, via Wikipedia:

Jakub (or Jakob) Schikaneder (February 27, 1855 in Prague – November 15, 1924 in Prague) was a painter from Bohemia.

Jakub (or Jakob) Schikaneder was born to a family of a German customs office clerk in Prague. The family’s love of art enabled him to pursue his studies, despite bad economic circumstances. The aspiring painter was a descendant of Urban Schikaneder, the elder brother of librettist Emanuel Schikaneder.

Following his work in the National Theatre, Schikaneder traveled through Europe, visiting Germany, England, Scotland, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy and France. From 1891 until 1923 he taught in Prague’s Art College. Schikaneder counted amongst those who admired the Munich School of the end of the 19th century.

Schikaneder is known for his soft paintings of the outdoors, often lonely in mood. His paintings often feature poor and outcast figures and “combined neoromantic and naturalist impulses.” Other motifs favored by Schikaneder were autumn and winter, corners and alleyways in the city of Prague and the banks of the Vltava – often in the early evening light or cloaked in mist. His first well-known work was the monumental painting Repentance of the Lollards (2.5m × 4m, lost). The National Gallery in Prague held an exhibition of his paintings from May 1998 until January 1999. [2]

Credits and Attributions:

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Jakub Schikaneder – Evening Street – Google Art Project.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Jakub_Schikaneder_-_Evening_Street_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg&oldid=844404638 (accessed February 22, 2024).

[1] Copilot GPT drew information and quotes from these sources (accessed February 22, 2024):

- https://www.wikiart.org/en/jakub-schikaneder/evening-street |

- https://www.artrenewal.org/artworks/street-in-the-evening-prague/jakub-schikaneder/100011 |

- https://fineartamerica.com/featured/5-evening-street-jakub-schikaneder.html |

- https://www.wikiart.org/en/jakub-schikaneder

[2] Wikipedia contributors, “Jakub Schikaneder,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jakub_Schikaneder&oldid=1188016975 (accessed February 22, 2024).

![By Robertgrassi (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/villa_diodati_2008-07-27_rg_5.jpg?w=300&h=225)

However, that which was once canon regarding vampires is no longer set in stone.

However, that which was once canon regarding vampires is no longer set in stone.